They may have not gone to the same school or grown up in the same neighbourhood, but these five young men have one thing in common -- an insatiable passion for satellite technology, reports bdnews24.com.

It was this shared interest that brought them together when they first met each other at a space technology camp. It marked the beginning of an ambitious venture to build a rocket, or in their words, ‘rocket mission’.

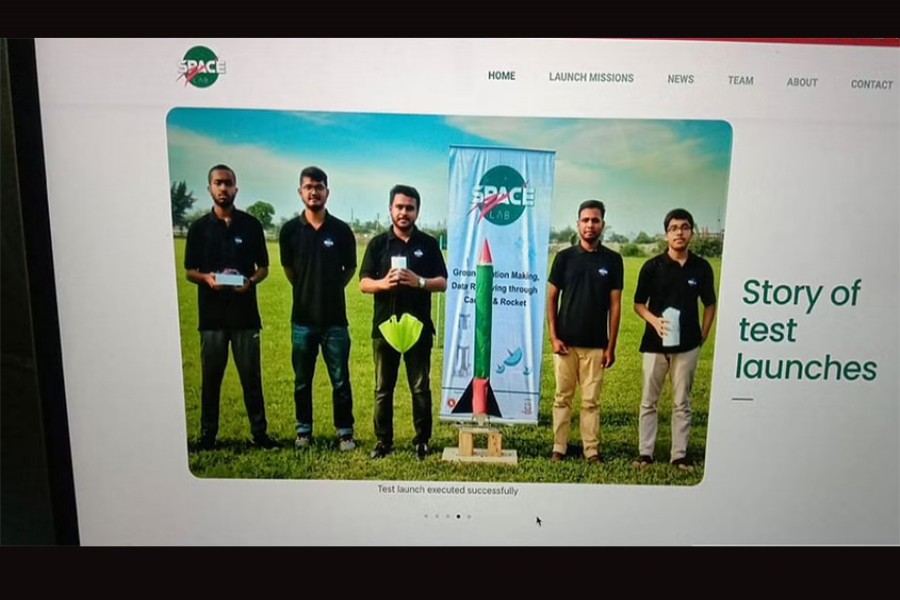

In an exclusive sit-down with the news agency, Md Shahadat Hosain Riyad, Md Mehrab Haque, Tahsin Hossain, Md Ekramul Hasan Chowdhury, and Abu Sayeed looked back on their journey so far and shed light on their dream project.

HOW IT STARTED

In 2018, Riyad launched his own start-up company called Spacelab. He participated in the Space Innovation Summit that year, where he decided to make a CanSat [soda can-sized satellite] and also, conduct the first drop test in Bangladesh. He already had the experience of mentoring at the NASA Space Apps Challenge.

Mehrab was a member of the team representing the Dhaka Division that became champions at the NASA Space Apps Challenge.

In 2019, Abu Sayeed worked as a mentor to children at the Space Innovation Camp, organised by the Bangladesh Innovation Forum, where he taught how to make rockets.

Ekramul also took part in the innovation camp at United International University (UIU). Tahsin built a water rocket at the camp.

All five of them felt a strong urge to “do something more” in their area of interest.

WHAT IS A DROP TEST?

A drop test is a method of testing the in-flight characteristics of a prototype or experimental aircraft and spacecraft by raising the test vehicle to a specific altitude and then releasing it.

The five youngsters gradually began gathering and disseminating the combined data from a ground station, can satellite and water rocket.

They submitted their project to the government’s ICT Innovation Fund competition in 2021.

After rigorous scrutiny, they bagged government funding for their project and were assigned a mentor to guide them.

Ariful Hasan Opu joined the team of five as a supervisor.

Opu, the founder of the Bangladesh Innovation Forum, provided the background for the project. The quintet have been working on the project for two years, he said.

Ariful Hasan Opu joined the team as a mentor and supervisor.

Ariful Hasan Opu joined the team as a mentor and supervisor.

“Finance was an issue, but the lack of supervision was more pressing. I was a judge at the ICT Innovation Fund competition. When their application was selected, the government officially appointed me as the mentor for this project.”

PROJECT PROGRESS

As part of a test project, the innovators were supposed to make a ground station with three sensors within the first six months. But, the team led by Riyad had five sensors on hand by then, adding two more in June 2022.

“Now, we can collect data from the ground station using seven sensors,” Riyad said.

Having conducted a few trials, they held a proper test with five sensors on Oct 13, 2021.

A water rocket was launched up to an altitude of 26.78 metres, or 87.86 feet, from a big, open field on the UIU campus in Dhaka’s Madani Avenue.

Afterwards, the group successfully collected data from a drop test with seven sensors added to the rocket.

“We have three issues here: deploying a can satellite to space using a water rocket, making the circuit and the entire system using easily available electronic machinery parts -- we used sensors for this. And the last one is an open source ground station,” Riyad, chief technical officer of Spacelab, explained.

Bangladesh is yet to start using an ‘open source customised ground station’ to conduct drop tests, according to Opu.

The canopy opens just as the CanSat separates from the water rocket after it reaches its maximum altitude.

The canopy opens just as the CanSat separates from the water rocket after it reaches its maximum altitude.

“We embedded the open source ground station mechanism software used by MIT and NASA into the can satellite mechanism. This made data collection easier.”

“We aim to build a sustainable module so that students and young people can do more practical work with satellite rockets,” he said while outlining the group's aim of creating a community.

“For example, if someone in Rajshahi works on a satellite, they can upload the data and add it centrally to our previous data.”

WHAT’S A WATER ROCKET MADE OF?

The experimental project undertaken by the group involves water rocket technology as it is cheaper to build than a fuel-propelled rocket, according to Opu.

The team was seen with a green, cylindrical-shaped water rocket, with three triangular parts at the bottom -- reminiscent of the spacecraft built by NASA.

The rocket was installed on a wooden launch pad, which had a manual gear or lever attached to it. The team plans to automate the lever one later.

The red, cone-shaped part on the top of the rocket is known as the nose cone. The rocket, with a cylinder made of plastic bottles and a nose cone, stands 4.5 feet tall. It has a 25mm radius.

The CanSat sends data while the ground station circuit collects it. The information is then analysed by the ground team.

The CanSat sends data while the ground station circuit collects it. The information is then analysed by the ground team.

Two-thirds of a water rocket is composed of compressed air and one-third is composed of water. During the launch, 80 to 125 PSI (pound per square inch) of air pressure is usually pumped into the rocket.

Then, the lever is pulled and the rocket blasts off into the sky.

A water rocket has a fixed volume and the compressed air inside pushes on the water as it tries to expand. The water pushes downwards through the nozzle and rushes through it, creating a thrust to counter the weight and air resistance. The thrust pushes the rocket upwards into the sky.

CAN SATELLITE

A can satellite or CanSat is a simulation of a real satellite, integrated within the volume and shape of a soft drink can.

The most important part of this project is data collection and distribution. The CanSat is used to send data while the ground station circuit collects it. The information is then analysed.

At one point after launch, the CanSat detaches from the rocket and begins a rapid descent. Due to gravity, its force increases the closer it gets to the ground.

The CanSat typically hits the ground hard and disintegrates if its speed is not reduced. That is why a parachute is attached to it to avoid friction.

Before blast off, both the CanSat circuit and the parachute are inserted into the upper part of the rocket, Tahsin explained.

Before launch, both the CanSat circuit and the parachute are inserted into the upper section of the rocket.

Before launch, both the CanSat circuit and the parachute are inserted into the upper section of the rocket.

"The parachute adds terminal velocity. Due to this, a force equal to the mass of the CanSat works upwards from both sides. This takes the resultant force to zero."

"Then, acceleration won't work on the CanSat and it will come back down at a specific velocity"

The size of the parachute or canopy depends on the terminal velocity of the CanSat, Tahsin added.

“If we need higher velocity to drop the CanSat, a smaller canopy will be required. Similarly, we'll need a bigger canopy if we want the CanSat to drop slowly.”

The CanSat made under their project weighs around 500 grams, and therefore, the weight of the parachute is not that important, he said.

“But canopy weight is very important for the spacecraft made by NASA that land on water. In that case, the size and materials of the canopy become an issue.”

Their initial canopy had a diameter of eight to nine centimetres, he said.

“The aim was for the canopy to open just when the CanSat separates after the water rocket reaches the ultimate altitude. But it took time for the canopy to open.”

“The delay was caused by a mechanical glitch. Afterwards, the canopy opened and the CanSat landed at a linear velocity,” said Tahsin, the youngest member of the group.

Once the launch pad lever is pulled, the water rocket shoots up into the sky.

Once the launch pad lever is pulled, the water rocket shoots up into the sky.

The team will further monitor the issue, but more work is needed on the mechanical design, according to him. “I want to expand the area of the parachute.”

“Then, it will descend slower and we’ll get more data. And if we’re able to launch the rocket to a higher altitude, it will provide us with much more data.”

DREAM OF MAKING A ROCKET

Both Abu Sayeed and Ekramul have experience in building rockets.

Abu Sayeed is studying aeronautical engineering at the College of Aviation Technology, while Ekramul is a final year student of electrical engineering at the Dhaka Polytechnic Institute.

“Since I was a child, my father used to encourage me to work on robotics. I, too, nurtured a dream of working on robotics and rockets," said Ekramul.

After working on some satellite-based projects, Mehrab wanted to work on space technology.

"This project involved some work on lights in the CanSat and I have prior experience in working with microcontrollers. Altogether, this project has been the best fit for me," said Mehrab, a computer science and engineering student at BUET.

When he was a tenth grader, Tahsin developed an interest in rocket satellites. Later, he completed some online courses on the subject.