The regulatory body and experts' repeated insistence on long-term stock investments for high returns falls on deaf ears, reflected in the overall market's behaviour.

But a quick calculation may help translate the message given -- in black and white.

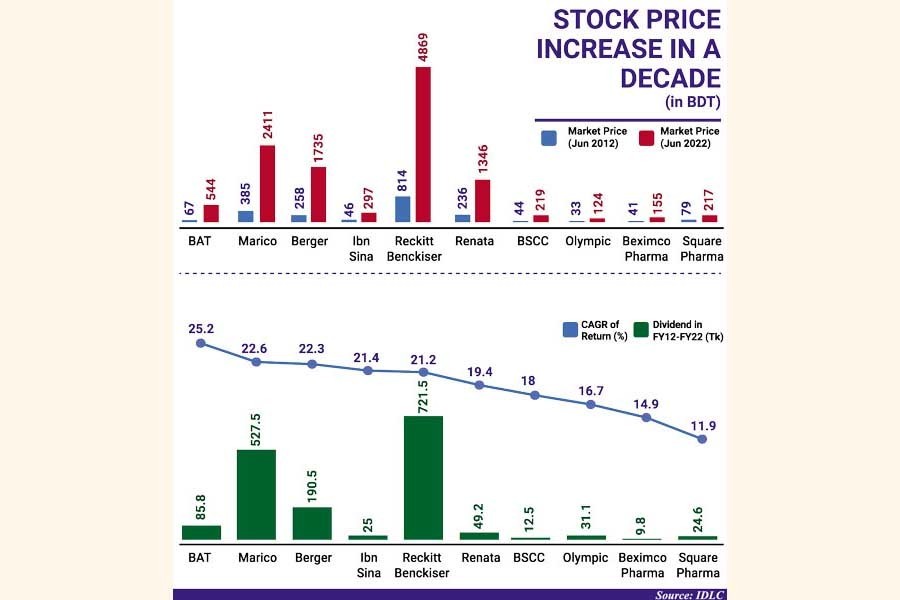

Take for example; an investor bought a share of British American Tobacco Bangladesh at Tk 67 at the end of the FY12. By that time the valuation of shares had been diluted by additional shares injected into the market.

If the investor kept the holding for the next decade, he would receive dividend yields of Tk 85.8 in total. Also, the market price of the share would go up to Tk 544 in June 2022.

Putting the numbers into the formula of compound annual growth rate (CAGR), the investor discovers that they would receive a return at 25.20 per cent on the investment made if the share was liquefied at the end of the FY22.

The income seems impressive, when compared with the 4-12 per cent interest rates on fixed deposit receipts (FDR) and the returns from National Savings Certificate.

The purchasers of savings certificates received interests at 11.5-12 per cent in the period of 2006-09, at 12.5-13 per cent in 2012-2015 and at around 11-11.3 percent thereafter.

The question is how long an investment should be to consider long-term.

Many market operators think investments for at least one year is mid-term while shareholders have to keep their holdings for at least three years to reap the benefits of long-term investments.

On the other hand, stakes held for at least a quarter are short-term.

If the five years' average return of 11.6 per cent from savings certificate is taken into account, the amount too will fall much short of the income promised by fundamentally-strong stocks.

With the money spent on purchasing the BAT share instead of any other fixed-income securities, the investor could have good enough cash in hand even if inflation had squeezed the purchasing capacity. The country's annual average inflation rate hovered between 5.44 per cent and 7.50 per cent in the decade.

Market insiders say returns from listed companies should be above 13 per cent, close to the country's nominal economic growth of 12-13 per cent.

Besides, investments in stocks pose risks that are avoidable in guaranteed schemes, which is why expectations from listed companies are higher.

Like the tobacco company, other firms having a consistent profit growth also generated good incomes over a period of 10 years or less.

The CAGR of returns on investments on stocks, such as Square Pharmaceuticals, Beximco Pharmaceuticals, Renata, BRAC Bank, Berger Paints Bangladesh, and Marico ranged from 11.9 per cent to 22.60 per cent in the FY12-FY22.

Despite the optimistic results from long-term investments, the stock market is highly influenced by short-term trading by retail investors.

Around 20 per cent of the stocks listed with the bourses generated above 12 per cent returns on equity last year.

Managing Director of IDLC Investments Md. Moniruzzaman said the investment bank had set three criteria for choosing scrips for long-term investments.

Alongside good corporate governance, a company's return on equity must be 13 per cent for the last three years in a row while the earnings growth potential will have to be 15 per cent for the next three years.

"Companies for long-term investments are not many if these criteria have to be met," said Mr. Moniruzzaman.

Market operators say the large-cap companies that have had persistent business growths occupy a greater portion of the long-term investments.

Presently, the number of listed companies is 353, including the multinational ones with good fundamentals and good governance.

Usually, institutes and high net-worth individuals hold shares for longer periods, compared to individual investors.

The trading by retail investors accounts for around 80 per cent of the average daily turnover, but the scenario is reverse when it comes to shareholding.

"The market cap of good companies rises significantly owing to investments made for years," said Md. Ashequr Rahman, managing director of Midway Securities.

To him, stock buyers looking for quick gains are rather speculative participants, not investors.

"I am not willing to call them investors who chase stocks over rumours and then raise a hue and cry after burning their fingers," said Mr. Rahman.

More listing of good companies could encourage long-term investments and in turn stabilise the market. But an easy access to loans from banks, though it often increases the vulnerability of the financial institutions, for business expansion dissuades companies from going public, Mr Rahman added.