UK scientists have demonstrated the practicality of counting whales from space.

The researchers, from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), have been using the highest resolution satellite pictures available.

Even when taken from 620km up, this imagery is sharp enough to capture the distinctive shapes of different species.

The team will soon conduct an audit of fin whales in the Mediterranean.

The first-of-its-kind assessment will be partly automated by employing a computer program to search through the satellite data.

Current numbers on big species such as blue whales are very sketchy. Photo: BBC

Waters north of Corsica, known as the Ligurian Sea, are a protected area for cetaceans, and the regional authorities want to understand better the animals' movements in relation to shipping to try to avoid collisions.

Previous studies have played with the idea of spotting whales from orbit, but with limited success.

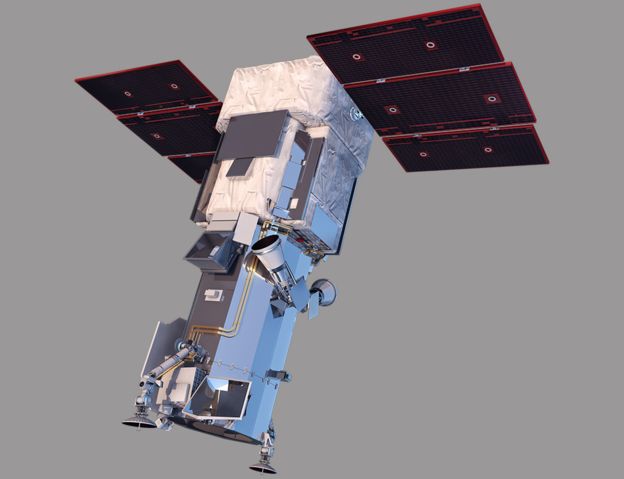

This new approach from BAS has drawn on imagery from the WorldView-3 spacecraft operated by the American company DigitalGloble.

WorldView-3 is able to discern things at the Earth's surface as small as 31cm across. Only restricted military systems see finer detail.

"Satellites have improved so much with their spatial resolution," explained Hannah Cubaynes, who is affiliated to both Cambridge University and BAS.

"For the first time we've been able to see features that are truly distinctive of whales, such as their flippers and flukes."

What have the scientists done?

Cubaynes' team examined WorldView-3 photos in different parts of the globe, looking for fin whales in the northern Mediterranean; humpbacks off Hawaii; southern rights around the Península Valdés, Argentina; and Pacific grey whales in Laguna San Ignacio, Mexico.

These are all baleens (filter feeders) and among the biggest cetaceans, reaching up to 15m or 20m in length.

The animals are detected just below, or even breaching, the sea surface. The fins and greys proved to be the easiest to identify in the pictures, in large part because their body colour contrasts well with the surrounding water and because they tend to swim parallel to the sea surface.

But, crucially, the team was able to make out the body shapes associated with the different animals, proving satellite-identification is a viable technique.

WorldView-3 produces the sharpest pictures in the public domain

Why count whales from space?

Currently, most surveys are conducted from the air, from boats and sometimes from a promontory, such as a high sea-cliff. But these are much localised searches, and whales are known to range across hundreds of thousands of square km.

Some of their feeding grounds will be far from land. Without more effective means to track the animals, we cannot really say how well they are recovering after centuries of over-exploitation.

"This is a potential game-changer - to be able to survey whales unhindered by the cost and difficulty of deploying planes and boats," said Dr Jennifer Jackson, BAS's top whale expert.

"Whales are a really important indicator of ecosystem health. By being able to gather information on the grandest scales afforded by satellite imagery, we can understand something more generally about the oceans' health and that's really important for marine conservation."

Don't we already count smaller animals from orbit?

This is true - to an extent. BAS has already pioneered the use of satellite imagery to monitor penguins and albatrosses, for example. But there are crucial differences.

In the case of penguins, it is not really individual birds that are counted; rather it is the general size of a colony that is assessed from the black mass of animals huddled together on the their ice habitat.

And in the case of albatrosses, the scientists know exactly where to look because the birds' breeding sites are restricted to just a handful of compact locations. A nest is just big enough to show up on a satellite picture, enabling an estimate to be made of the likely number of albatross pairs.

Spacecraft will gather huge image swaths when they pass over the ocean. With the exceptional resolution now available, counting individual whales becomes practical. In a 31cm-resolution image, for instance, a grey whale's fluke will take up 10 pixels.

Where does this research go next?

The team is now testing various algorithms that can search satellite images automatically.

The best will shortly be applied to a WorldView-3 dataset covering the Ligurian Sea.

"The whole area is 36,000 sq km. This is simply too big to search manually," said BAS co-researcher Dr Peter Fretwell. "It's a marine protected area and the worry is that there's a lot of boat traffic moving between Corsica, Italy and France.

"They're concerned about ship strikes and we may be able to establish some information about fin whales' behaviour that will be helpful to ships' captains."

Satellites continue to improve. DigitalGlobe, for example, plans a new constellation that promises to dramatically increase the rate at which the high-resolution pictures are acquired.

Allied to the latest data analytics techniques, this should be a boon to marine biologists and ecologists.

Not only will they get more robust numbers for live whale populations, but they should also have a much better idea of how many dead animals are stranding on remote coastlines around the world.

Cubaynes and colleagues have published their research in the journal Marine Mammal Science.