It was around 10:00pm when I found myself on a bus leaving Gimhae International Airport for downtown Busan in South Korea. The roads of the city that became famous in Asia for hosting the 2002 Asian Games, were brightly lit up. A bridge spanning the Nakdong River was festooned with colorful lights. Coming across such a site, not many would be able to dredge up the fierce war that took place there about 70 years ago.

Frankly, the night scene in Busan is no different than that in many big Chinese cities. Lights along the Huangpu River in East China's Shanghai and Pearl River in South China's Guangzhou are even brighter. But people could feel a glint of excitement when realization dawns that they are at the southernmost point of the Korean Peninsula.

The city was almost destroyed in the Korean War (1950-53), but now it is the world's fifth-largest port and is as well-known as big cities like Shanghai and Osaka. For many tourists from China, Busan is also known for the Shinsegae Centum City Department Store - the largest shopping complex in the world.

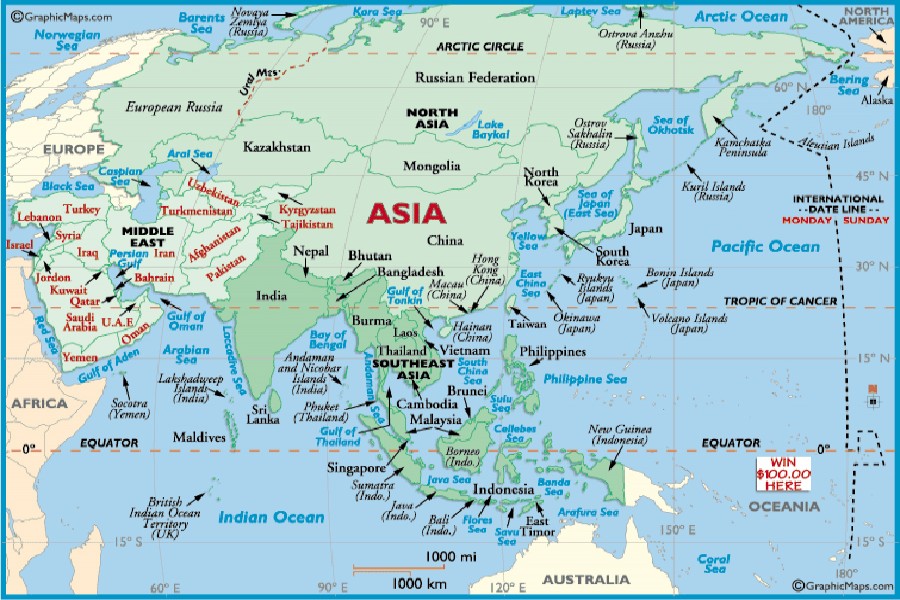

The city is an epitome of unprecedented prosperity in East Asia. China, Japan and South Korea have become powerful engines for the world economy, accounting for 23.5 per cent of world GDP in 2018 - almost equivalent to the share of the US. And the production capacity of the three countries is far ahead of any other region in the world.

However, after visiting some attractions in Busan, I began to have doubts about the extent of change that has taken place in East Asia. Whether I was in Busan Jungang Park, or in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery, or in the Busan Museum, or in front of a statue honoring Yi Sun-shin (1545-98) at the base of Busan Tower - who defeated Japanese aggressions various times in history - I didn't feel that history had moved away.

The sediments of history at the bottom of national consciousness are always looking for opportunities to come out to reveal themselves to the world - like in the trade dispute between South Korea and Japan. This seems to show the world that although the three East Asian countries have the ability to create development miracles, they are yet to find a key to get out of the historical trap.

Over the decades, East Asia has been developing in sync with a pattern derived from the Cold War. Even after the Cold War, security in the region is not free of US dominance. Historical disputes, which were once obscured by the Cold War, have not been completely resolved. The Military Demarcation Line (MDL), widely known as the 38th Parallel, is a proof that the Cold War has not really ended.

The three East Asian countries have transformed into major economic powers. A new era in which the US can no longer play a dominant role has begun.

Yet how can the regional political and security architecture, which until now was dominated by the US, morph into a new framework led by cooperation among the three countries? That prospect remains uncertain. Quite a few aspects, which have a fondness for the status quo or embody an inertia to change, are acting as an impediment.

Some Western scholars attribute the uncertainty in East Asia to China's emergence. But anyone who has visited big cities in the region such as Shanghai, Beijing, Seoul, Tokyo and Busan, would find out that East Asia has been rising as a whole.

The rise of countries here is closely intertwined. This is the trend. China's emergence has brought the possibility of the birth of a new pattern in East Asia.

Singaporean academic and former diplomat Kishore Mahbubani is one of the first scholars to predict the rise of Asia. But he is more focused on reminding the West that it must change its ways to observe and recognize Asia. The largest continent itself is the key to spawning more certainties for development.

How to walk out of history in a peaceful and Asian way and establish a system given to sustainable peace and development, which could gradually replace the US-led Asian pattern, will be the real test for countries in the continent, especially for China, Japan and South Korea.