In global trade arena, the tariff protection mechanism practised by the importing countries are losing its attraction due to bilateral, regional and plurilateral trade liberalising agreements. Due to World Trade Organisation (WTO) disciplines and member's schedule of tariff commitments, raising tariffs (beyond allowable limits in WTO) to protect domestic industry is difficult. As such, protectionism in trade is now applied using Non-tariff Measures (NTMs), Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs), and other trade remedies such as, Anti-dumping, Countervailing and Safeguards. A product would be considered as dumped when an exporter sells a product for export to the importing country at a lower price than the price at which the same (or like) product is sold on its own domestic market (called Normal Value).

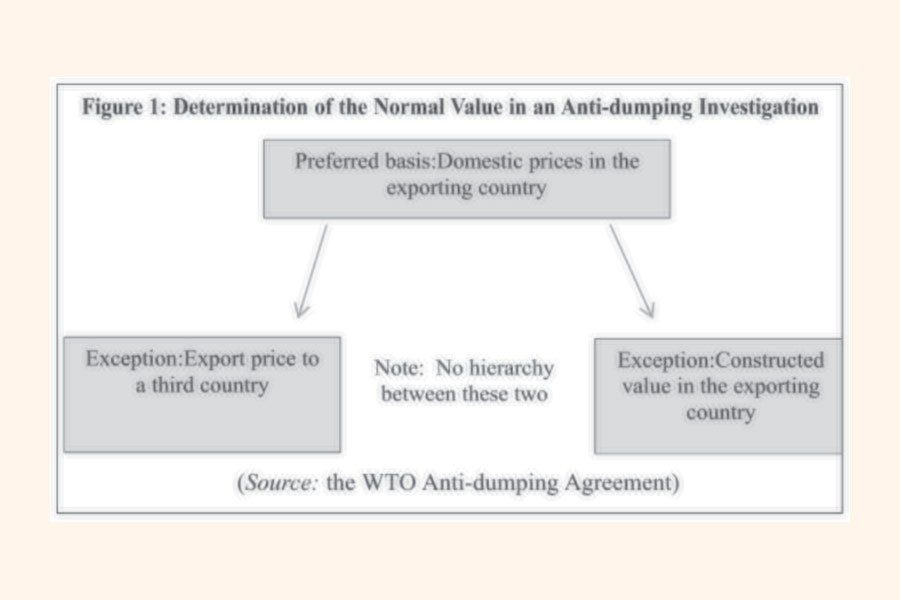

When normal value cannot be determined on the basis of domestic prices in the exporting country (if the normal value of the dumped product, i.e., the price offered in the domestic market, is not available to determine the level of dumping), the competent authority can determine the normal value in two alternative ways. These are:

- Third-country market price: the price charged by the exporter in another country (known as third-country market price); or

- A constructed value: The constructed value can be obtained by adding to the cost of production of the like product in the country of origin a reasonable amount for selling, general and administrative expenses and for profits. (This is referred to as constructed normal value).

There are three possible options under anti-dumping agreement to determine the normal value of the products under investigation. These three possible options are shown in Figure 1.

THE WTO ANTI-DUMPING LEGISLATION: Anti-dumping duty is a protectionist tariff that a domestic government imposes on foreign imports that it believes are priced below fair market value. Under the WTO Agreement on Anti-Dumping (i.e. Article VI of GATT 1994), members are authorised to impose specific anti-dumping duty when dumping causes or threatens to cause material injury to a domestic industry, or materially retard the establishment of a domestic industry.

Under the WTO Agreement on Anti-Dumping, WTO members can impose anti-dumping measures if they determine:

(a) that dumping is occurring;

(b) that the domestic industry producing the like product in the importing country is suffering material injury or threat thereof, or that the establishment of a domestic industry is being materially retarded; and

(c) that there is a causal link between the two.

INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENT IN BANGLADESH FOR ANTI-DUMPING: Bangladesh has taken an initiative to establish institutional arrangement for anti-dumping legislations. On November 30, 1995, the government of Bangladesh designated the chairman of the Bangladesh Tariff Commission (BTC) as the authority to deal with dumping matters through the SRO 210-ain/95/1643/shulka. The BTC has published guidelines, including guide to the completion of a dumping complaint.

ANTI-DUMPING MEASURES AGAINST EXPORTS OF BANGLADESHI JUTE PRODUCTS: In recent times, three complaints of anti-dumping on Bangladesh have been launched by India and Pakistan. One of the three, relating to jute, was launched by India. Indian Jute Mills Association (IJMA) filed an application to the designated authority. i.e., Directorate of Anti-Dumping & Allied Duties (DGAD), Ministry of Commerce, India, for initiation of an anti-dumping investigation and imposition of anti-dumping duty on the imports of "Jute Products" from Bangladesh. The DGAD sent a questionnaire to 258 exporters (including government jute mills) in Bangladesh but only 26 of them responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 11 jute mills faced different anti-dumping duties on their products on mill-basis. The duty varies from mill-wise and ranges from $19.30/MT to $152.85/MT. Twelve faced similar duties on product-basis, the duty amount ranges from $97.19/MT to $371.72/MT. (The anti-dumping duty amount was equal to lesser of the margin of dumping and margin of injury keeping in view the lesser duty rule). The DGAD did not find any evidence of dumping in the case of two jute mills (Hasan Jute Mills for Jute Yarn/Twine and Sacking Bags and Janata Jute Mills for Hessian Fabrics) and thus they did not face any anti-dumping duties. Exporting firms, who did not respond to Indian queries, faced higher duties (source: DGAD, India, Final Findings by DGAD India, 20 Oct 2016).

It appears that the exporting jute mills of Bangladesh could not defend their cases against the complaints made by Indian firms, resulting in their facing anti-dumping duties. The reasons for the very poor response rate (26 out of 258) in completing the DGAD questionnaire by the jute goods exporters, as well as their inability to defend their cases (by properly filling in questionnaire), seem to include: 1. questionnaires used in anti-dumping duty investigations are complex; 2. ordinary businesses do not have the requisite skills and knowledge to handle the highly technical dumping issue; 3. perhaps many of them could not understand the grave consequences of the investigation, and did not take the issue seriously; and 4. many of these 258 exporters were not in operation (closed) at the time of investigation. An official confided that the Indian importers made more effort (as they will lose ground to Indian local manufacturers if ADD is imposed) than the exporters from Bangladesh to resist imposition of anti-dumping duty.

The major challenges for Bangladeshi exporters are their lack of awareness on the issue, lack of capacity to effectively handle complex dumping investigation and their insensitivity towards such measures. Bangladeshi exporters as well as the competent authority do not have any experience on this.

This makes it clear that the level of awareness about anti-dumping issue and the level of capacity for initiating a case or for defending a dumping investigation need to be increased.

Both the regulatory authorities of Bangladesh and business enterprises have to enhance their understanding and maintain comprehensive accounts to deal with anti-dumping cases in line with the WTO rules. The trade bodies, chambers of commerce and other stakeholders can play a vital role in supporting individual exporters in facing dumping investigation. They can also provide comprehensive evidence of dumped imports (if any) and ask for investigation and imposition of anti-dumping duty. In order to do this, local manufacturers and trade bodies will have to increase their capacity and provide detailed evidence/documents in support of their claims. For example, Indian jute product producers submitted detailed accounts of their production, sales, exports, statement of Indian production and standing, injury statement, list of Indian producers, normal value calculation (item-wise), and net export price calculation in their petition for imposition of anti-dumping duty on imports of jute products. Bangladeshi producers need to upscale their skills and database.

Moreover, the businesses of Bangladesh need to adopt the international standards on Cost & Auditing. It will definitely improve their capability and competitiveness in global market as well as help them to deal with any anti-dumping cases against them. In addition, the government institutions, such as Bangladesh Tariff Commission and Competition Commission can assist the businesses to file and face anti-dumping cases. Creating a pool of both legal and technical experts is necessary. Meanwhile, in facing the dumping investigation by DGAD of India, Bangladesh Tariff Commission (BTC) offered its assistance to the jute goods exporters. However, the BTC was practically in the dark as to what the jute goods exporters' responses were to the DGAD questionnaire. Only one company shared their information (responses) with the BTC.

A cooperative approach between the manufacturers/exporters and the BTC is essential to jointly uphold the interest of the country. It is high time that our traders and respective agencies understood the new dynamics of international trade, and strengthen each other's position, through mutual sharing of information and knowledge.

Tapas Chandra Banik is Research Associate, Bangladesh Foreign Trade Institute. Mohammad Abu Yusuf PhD is Customs Specialist, USAID-BTFA. The opinions given in this article are those of the authors and in no way

reflect the views of the organisations they work for.