The first Amar Ekushey programme at the Central Shaheed Minar in Dhaka in free Bangladesh was held without any disruption. Few in the country had expected that the Victory Day on 16 December would arrive in the besieged land after mere nine months. They had never thought of observing the great Language Martyrs' Day in the near future -- that too amid a triumphant mood, dominated by its usual solemnity, and with the participation of thousands of students and general people. The great symbol of the day, the concrete-made imposing monument was, however, not there. A hastily built makeshift Shaheed Minar stood in its place.

The original monument was completely destroyed by shells fired by the marauding Pakistani soldiers on the night of March 25 in 1971. It lay in a heap of concrete rubble for nine long months. Thanks to the nation's great victory in the Liberation War, Bengalees did not have to skip the Language Movement observance even for once.

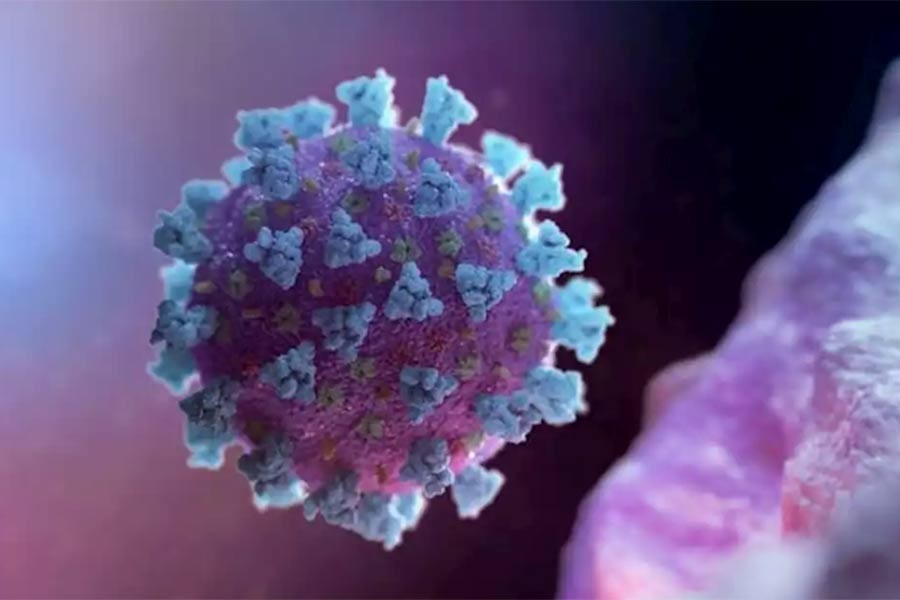

The nation is passing through another calamity, worse than the 1971 genocide in some respects. Here the enemy is a terrible disease. Like with all such scourges, its invisibility adds to its dreadfulness. Against the backdrop of its protracted and insidious spread, the government has enforced a plethora of containment measures. Shutdowns and maintaining social distance by staying at home for days in a row are the two prominent of them.

To the disappointment of many, the government has recently announced the cancellation of the Bangla New Year's festival for this year. The colourful event was supposed to be celebrated on April 14. Ever since the start of welcoming the Nobo-Borsho, the Bangla New Year, in great jubilation, the festivity's celebration hasn't seen any break. The ceremonial welcoming of the year began a few years after the country's independence. The custom of greeting the Bangla New Year, however, began in the early sixties. To mark the occasion, a few hundred culturally enlightened people used to assemble early in the morning every year at Ramna Park in the city on the 1st day of Baishakh, the first month of the Bangla calendar.

The day was not celebrated in occupied Bangladesh in 1971. Cultural organisations refrained from organising functions marking the birth and death anniversaries of Rabindranath Tagore, the great poet. They feared attacks from the occupation army authorities. The Pakistani junta had always viewed the songs and other works of Rabindranath Tagore as being detrimental to the promotion of Islamic spirit of Pakistan. His songs remained under a ban throughout the decade of the 1960s. A great number of works of the Rebel Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam also drew the ire of the then Pakistani authorities owing to their humanistic spirit.

A lot of other socio-cultural events advocating Bengalee nationalism remained suspended in the later part of the Pakistani state. The hostile stance of the authorities reached its peak in 1971. As has been seen in history, exogenous events at times stand in the way of the smooth march of sectors related to the arts and scholarship and sport. Humanity has been used to seeing the monstrous faces of these occurrences, which finally became unforgiving stumbling blocks to the march of man. The World War II was one such hindrance.

Thanks to its savage nature, scores of literary-cultural and sport events had to be postponed or cancelled during the war's six-year span. Notable of them were the six Nobel Prize ceremonies and two Olympic Games. Those fraternity-promoting assemblages eventually turned out to be collateral victims of human madness. COVID-19 is not driven by some dictators' greed and barbarity. It has its unique course of marauding. Like in the brutal wars, a few human attainments became the victims of its collateral damage. The pandemic hasn't spared this year's Tokyo Olympic and many other global festivities.