In mid-August, President Trump asked US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to open an investigation into China's intellectual property (IP) practices. "This is just the beginning," Trump told reporters.

In turn, Lighthizer, a veteran Reagan administration trade hawk, seized the notorious Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which in the 1980s was used against the rise of Japan.

The investigation could lead to steep tariffs on Chinese goods - but it could also trigger a global trade war.

CONTRADICTORY VIEWS: Since the early 2010s - in parallel with the dramatic rise of Chinese innovation and outward direct investment - the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property has argued that the plunder of American intellectual property is a systemic threat to the US economy in which China has a central role. As US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross put it in the Financial Times last August: "American genius is under attack from China."

According to the Commission, IP theft amounts anything between $225 billion and $600 billion annually in counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets. While the Obama administration and Congress enhanced the policy mechanisms to mitigate IP theft, the Commission believes it is time to implement more "aggressive" policies to protect American IP.

While the Commission believes that the Chinese government "forces" US companies to relinquish its IP to China, US IP experts that work on IP transactions in China find little evidence of such practices. What is more typical are transactions in which Chinese public companies and state-owned enterprises have pushed hard to get the other party - US, European and Japanese companies - to part with its IP for a low price. Foreign companies operating in China do not adequately protect their technology, or believe that partnerships automatically protect their technology. From the IP standpoint, many foreign companies, particularly SMEs and technology startups, do not appropriately understand IP risks, feel that they do not have other choices for financial reasons, or have misguided views of their IP protection.

In highly regulated and strategic industries, Chinese overview is more stringent but that applies to both Chinese and foreign companies. Conversely, Chinese companies have faced many barriers in the US in similar strategic areas, from CNOOC's failed effort to buy US oil company Unocal (eventually acquired by US-based Chevron) to Huawei's failed attempt to invest in America (which led to congressional hearings).

Interestingly, in contested legal cases, Chinese government has often supported foreign companies. As the Wall Street Journal reported last year, when foreign companies sue in Chinese courts, they typically win. From 2006 through 2014, foreign plaintiffs won more than 80 per cent of their patent-infringement suits against Chinese companies, virtually the same rate as domestic plaintiffs.

In fact, it is a not-so-secret secret that for years foreign multinationals have been exchanging their technology expertise for market share in China (and several other large emerging economies). Semiconductors are a case in point. Reportedly, technology transfers increased significantly amid the global crisis in 2007-9, when Intel, which then made over 70 per cent of its sales outside the US, opened a $2.5 billion wafer fabrication foundry in Dalian, northeast China. In contrast to simple assembly plants, these "fabs" represent the tech giant's IP crown jewels. Unsurprisingly, the move attracted many other foreign technology companies to create a foothold in the mainland.

As the global crisis dragged major advanced economies into stagnation but China grew vigorously another half a decade, that bet proved very lucrative. At the time, Intel's chairman was Craig Barrett, former CEO. Yet, today Barrett is one of the commissioners of the US IP Commission who would like to challenge China's IP practices.

ADVOCACY IN THE NAME OF INDEPENDENCE: The Trump administration has relied heavily on the IP Commission, which provides ammunition to its "America First" views. It has been portrayed as an independent actor in the IP debate. But that portrayal is not valid.

The IP Commission is co-chaired by Dennis Blair, former US Director of National Intelligence and Navy admiral who was commander of US forces in the Pacific; and Jon Huntsman, Trump's current ambassador to Russia and former ambassador to China who left his post after a controversial appearance amid a planned pro-democracy protest in Beijing.

In addition to Intel's Barrett, the Commissioners include veteran senator Slade Gorton whose focus is on economic and trade threats against America, from the "9/11 Commission" and the bipartisan Partnership for Secure America to the Slade Gorton International Policy Center funded by the National Bureau of Asian Research. The latter originates from the '70s, when the anti-communist Senator Henry M. Jackson, a hero of the neoconservatives, raised the need for what was initially called a "National Sino-Soviet Center."

The IP commissioners also include former US Deputy Secretary of Defence William J. Lynn III, a longtime lobbyist of Raytheon, a major $25-billion US defence contractor that is focused on crushing China's air defences, among other things. In turn, Deborah Wince-Smith is President and CEO of the US Council on Competitiveness who swears in the name of "Made in America," has criticised China-Canada free trade agreement and expects US to replace China as the leading global manufacturer by 2020. Finally, Michael K. Young, the President of Texas A&M University, is a Mormon official who served in President Bush's US Commission on International Religious Freedom and remains an ardent advocate of religious freedom and global democracy.

Of course, the point is not that these members of the US Commission are not qualified. On the contrary, all are highly-regarded in their respective areas of expertise. Rather, the point is that the Commission is not an independent or a neutral broker. Rather, it is a highly partisan advocacy group for "America First" interests operating outside yet closely with the government.

HISTORICAL TIMING OF THE IP DEBACLE: On October 10, the first public hearing about Chinese trade conduct took place in Washington, DC. Afterwards, Bloomberg reported the obvious: "Trump Is Warned His Intellectual-Property Probe Risks a Trade War With China." Led by the US Trade Representative, Office of Intellectual Property and Innovation, and the Council of Economic Advisers, the hearing involved four panels, which reflected IP, legal, business and union interests, along with the views of US and Chinese think-tanks.

Unsurprisingly, government officials argued that "China's IP theft" represents the "greatest transfer of wealth in history," which was seconded by the IP Commission's opinion of China as a "party state" in which "companies are afraid to report abuses." In contrast, legal experts praised China for strides in "combating counterfeit products" suggesting that US government views were "completely untrue." Interestingly, business interests sought to push back aggressive claims of forced IP transfer.

The dissension illustrates a clash between facts, myths and ideological views on Chinese IP. Historically, the timing of the IP friction itself is relevant.

The current IP debacle is escalating at a historical moment when Chinese companies are beginning to compete among world-class leaders, cutting-edge innovation and lucrative brands. The shift is reflected by increasingly global struggle for innovation. According to the number of total patent applications, China's role exploded since mid-2000s. Two decades ago, it was still far behind the US, Japan, South Korea and Germany, the world's leading patent players. Now it is ahead of all of them (Figure 1).

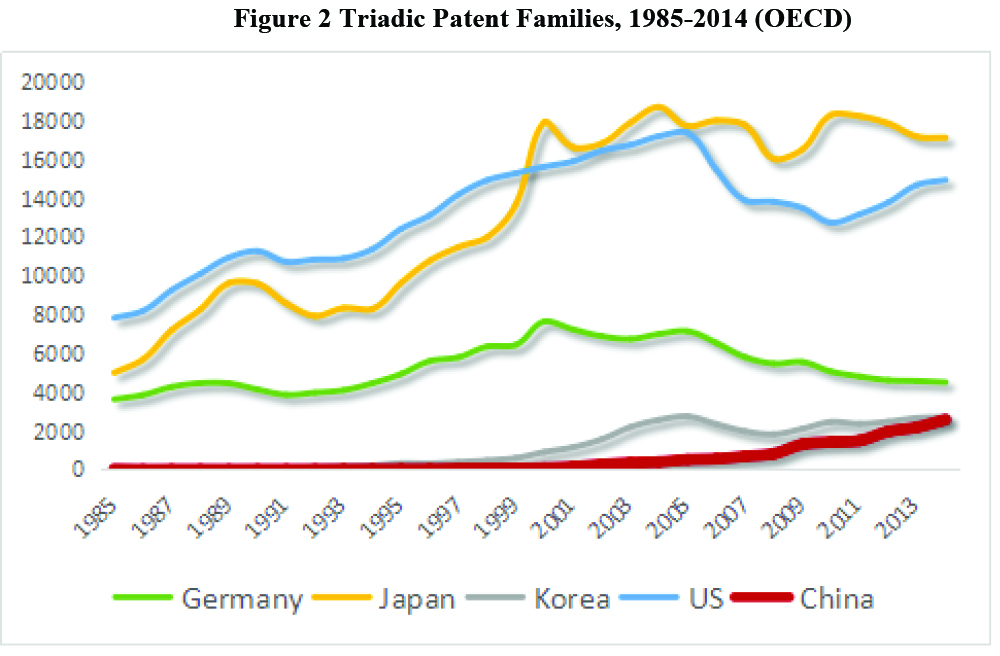

But in these rivalries, not all patents are of equal value. The so-called triadic patents, which are registered in the US, EU, and Japan to protect the same invention, tend to be the most valuable. In triadic patents, too, China's patent power has increased dramatically and is about to surpass that of Korea and Germany. The patents of Japan and the US peaked around 2005-6. Despite some progress, US patents are still 15 per cent below their peak, whereas those of China increased more than sixfold in the past decade (Figure 2).

Now, since patent competition is accumulative, catch-up requires time. But here's the thing. Yet, the trend line is clear: If, for instance, US and Chinese triadic patents would increase in the future as they have in the past five years - which is likely because, despite growth deceleration, Beijing is accelerating the economy's rebalancing from investment and exports to innovation and consumption - China is likely to surpass the US by the late 2020s. And perhaps that's why Trump is targeting China's IP today.

Not surprisingly, some US observers suspect that the Trump administration's IP investigation is less a scrutiny of forced technology transfers than a negotiation ploy to start bargaining from a more favourable starting-point. That's typical to Trump's tactics, as spelled out in his Art of the Deal (1987). But it is also a Pandora's Box that can undermine progress in US-Chinese trade and further penalise global growth prospects.

In fact, much of China's IP progress can be explained on the basis of past technology transfer and the government's high investment in science and technology. Moreover, as Chinese companies have rapidly moved up the value-added chain, they have begun to emphasise the need for IP protection.

Indeed, the Trump administration could achieve far more in innovation by steering greater investment into new and emerging technologies in the US than penalising China for its progress.

Dr Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served as research director at the India, China and America Institute (USA) and visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore).