When I first met him in his office in Camden, London, it was with love that he spoke of Bangladesh, of the experience of the country that had become part of his memory. The time was the late 1990s and I was new in Britain, with the responsibility of manning the press wing of the Bangladesh High Commission. In what I considered to be get-acquainted meetings with British journalists, especially in the mainstream newspapers, I visited a number of media offices and found it worthwhile interacting with the people who kept their organisations going.

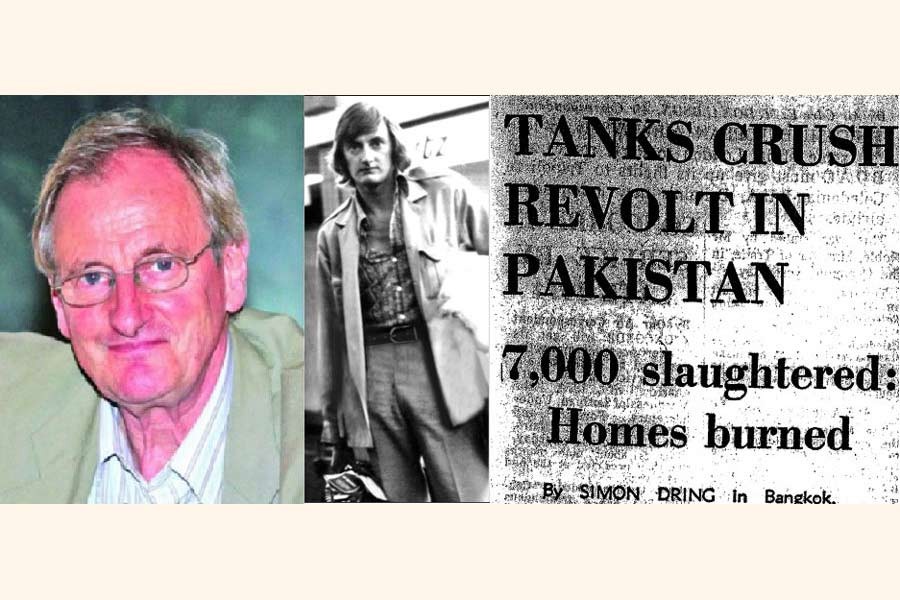

And then I decided to see Simon Dring. We spoke on the phone and a couple of days later I was in his office, marvelling at the man who had filed that report from Bangkok which had brought to the attention of the world what had been happening in occupied Bangladesh. As we sat down in his office, over tea, I recalled the opening lines of his report, 'Tanks crush revolt in East Pakistan':

'In the name of "God and a united Pakistan", Dacca is today a crushed and frightened city.

After 24 hours of ruthless, cold-blooded shelling by the Pakistan Army, as many as 7,000 people are dead, large areas have been levelled and East Pakistan's fight for independence has been brutally put to an end.'

That was Simon Dring. In that office room of his, he gave me a graphic description of the atrocities he had witnessed in the few hours before he would make his way out of Dhaka. He was not supposed to be there at that point, for the army had rounded up, prior to the launch of its operations, all foreign newsmen who had been covering the political crisis and put them on aircraft flying out of Dhaka. I asked Simon how he had managed to elude the soldiers, for they knew he too was in the Intercontinental Hotel. It was sheer luck, as he put it. He had somehow managed to slip out of the group of the overseas newsmen and made his way to the roof of the hotel. The soldiers then went looking for him everywhere in the hotel, but it did not occur to them to go up to the roof to look for him.

Boarding a flight to Bangkok the next day, he was fortunate that despite the thoroughness with which the soldiers searched him --- pockets, notebooks, et cetera --- they could not get their hands on the notes that he had made of the military crackdown on the Bengalis. The first thing he needed to do, he told me, was to get the word out to the rest of the world of the carnage in Dhaka. On 30 March, his report appeared in the Daily Telegraph in London. The repression the Pakistan army had resorted to on the night of 25 March then exploded as a major story in the world's capitals. Simon Dring had done his job. The global media would then go full scale into the task of keeping tabs on the atrocities committed by the Pakistan army over the subsequent nine months.

I left Simon as a late afternoon began to give way to evening, promising to remain in touch.

Fast forward to the year 2001. On the day the machinations of the newly installed BNP-Jamaat government resulted in orders for Simon Dring to leave Dhaka, indeed to say goodbye to Ekushey Television, I called him on the phone. I had returned to Bangladesh a year earlier. I simply needed to tell Simon we were all with him, that the darkness into which we had been pushed would pass. Simon was extremely emotional on the phone. For a man who had braved all dangers in his career as a journalist, this crude attempt by a set of new rulers to undermine politics and the media in Bangladesh nearly broke his heart. But then he and I told each other that it was not the end of the world, that a better tomorrow would dawn.

As Simon left Dhaka on that dark day, I recalled the enthusiasm with which he had some months earlier invited me over to his office at ETV. He took me around, telling me all about the technology that ETV would employ in its reportage. ETV, he cheerfully informed me, would bring about a generational change in the dissemination of information in the country. It was obvious that, as a journalist with roots in a liberal West, Simon was looking to replicate some of that liberalism in Bangladesh's media world.

He and I went up to the roof of the ETV building in Karwan Bazar, where he pointed out all the instruments, antennae and all, that connected the channel to the wider world beyond Bangladesh's frontiers. And then he wondered, to my surprise, if I could be part of ETV. The thought was generous of him. I thanked him, letting him know that perhaps we could work together at ETV at some point despite my grounding in the world of newspapers. Simon was thinking of introducing an English language segment in ETV programmes.

As we in Bangladesh mourn the passing of Simon Dring, I remember the details he gave me of his journalistic experience in large parts of the world, especially Africa. There were the dangers he confronted everywhere, but the intrepid journalist that he was, Simon emerged from all such assaults unscathed. I recall his happiness over Eritrea gaining independence from Ethiopia. He was on very friendly terms with Isaias Afewerki, the guerrilla leader who had forced the Ethiopians into granting independence to Eritrea.

Simon was cheered by the simplicity and humility which Afewerki and his fellow guerrillas in the freedom struggle had made the norm in government. Of course, I wonder what Simon would think of the autocracy which Afewerki today presides over in Asmara. But all those years ago, he told me, the fact that Eritrea's leaders wore simple attire, had nondescript slippers on their feet and travelled around on their bicycles was reflective of a nation determined to claim its place in the sun.

In the report which is now part of Bangladesh's historical documentation, Simon Dring quotes an officer of the Pakistan army on the military operations in Dhaka and elsewhere. 'Nobody can speak out or come out. If they do we will kill them. They have spoken enough. They are traitors and we are not. We are fighting in the name of God and a united Pakistan', says the officer.

That was how our good friend Simon Dring let the news of the initial moments of the genocide go out to the world. As he passes into eternal silence, we know how intensely we will miss him, how warmly we have held him close to our hearts.

Let it be said again: Simon Dring carried Bangladesh in his soul. And we have given him a special niche in our history. As he goes forth to meet his Creator, we wave him a fond farewell. He was part of us, in these fifty years since he penned those loaded words damning an army that went around cheerfully murdering Bengalis.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a senior journalist and writer.