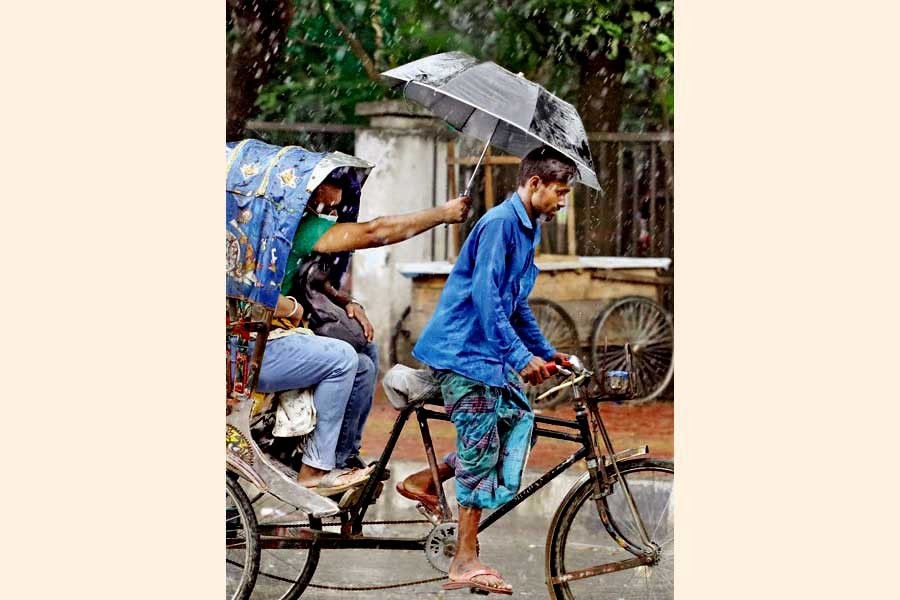

In a casual look, the photograph may seem nothing unusual. But upon an in-depth view, the uniqueness latent in it would be revealed to many. The photo printed on the first page of FE recently is one of common Dhaka scenes on a rainy day. It shows a rain-drenched rickshaw-puller pedallling his tricycle amid heavy downpour. Behind him a couple is found sitting under the plastic hood. What has made the photograph different is the male passenger's all-out effort to save the helpless puller from gettingsodden. He is seen holding an unfurled umbrella above the rickshaw-puller's head by extending his right arm. Apparently, this narrow-range umbrella-cover has prevented the puller from being fully drenched.

This kind of humane spectacle is rare in this ever-bustling city, but not too infrequent. Helping a blind youth with a white cane or an octogenarian woman with a small girl cross a traffic-filled road can be encountered often. These speak eloquently of a metropolis populated by many a compassionate person. But scenes of opposite nature are also there. A well-dressed young woman lying face down on aroadside apparently hit by a speeding vehicle, or while she was trying to get down from a local bus are not common spectacles. So are the briskly walking pedestrians going past her, showing little curiosity about what could have happened to her. Quite often, road accident victims are seen lying unconscious in a pool of blood. Few pause for even a while, and go about their business. These views of stony insouciance are unthinkable even in civil war-torn cities, notorious for their pervasive barbarity.

Few acts are more humanethan expressing sympathy for or standing by those fallen victim to unexpected hazards. Dangers do not come with prior notice. Barring humans with the so-called sixth sense none can realise in advance any approaching danger. Universally, mishaps befall man all on a sudden. The true human-selfprompts man to go to the rescue of those trapped in sudden dangers. Be it anywhere in the world, people with human qualities cannot let a helpless man or men or women drown in a river. On being prompted by their conscience, the rescue teams deploy their all-out initiatives to save fortune-seekers in mid-sea as they are battered by storm or cold. In mundane life, none will file cases against the men who cannot promptly carry a road accident victim to hospital. They think somebody else can perform the 'cumbersome' task better than them. This is escapism. Even if they can manage to bypass community rebukes, theycannot escape the interrogation of their own conscience, which plays the role of a judge.

In civilised cities, the law enforcement forces are omnipresent. Close-circuit cameras' surveillance of human and vehicular movement remains active without break. Even in this ever-heightened security alert and the blanket watching of public movement, isolated crimes do happen. However, those are confined to a few notorious neighbourhoods. Yet a passerby hit by a speeding car and lying unconscious with none coming forward to his or her help is an absurd scene there. Police patrols are omnipresent in these cities. Ambulances and hospitals' emergency wards are always ready to provide services to the victims.

However,the instance of a passenger helping a rickshaw-puller with his umbrella to keep him dry is extraordinary. This is no great deed. It is just a proof of how men of conscience stand by their fellow beings during their distress. Stunningly, a different segment of males verbally abuse a young woman walking home alone on a deserted road. This is sheer mockery of the compassionate treatment of a rain-soaked rickshaw-puller by his sympathetic passenger. Is man really a bundle of contradictions?

shihabskr@ymail.com