What's in a name? No matter how one calls a rose, it will continue to give its sweet smell. Thus felt Shakespeare. The people feeling troubled over the changes in the English spelling of five districts in the country could have taken recourse to the playwright. They haven't apparently. Instead, scores of others joined the chorus of disapproval. Many others have welcomed the step. After all, spellings of the names of the five districts of the country in English were introduced by the British colonial administration. Being a foreign power, they assumedly had little regard for the public sentiment. So they introduced the 'distorted names' by using an administrative fist. This being the popular notion suiting public consumption, some others may ask --- how could the misspelled names remain in official use for this long in the first place?

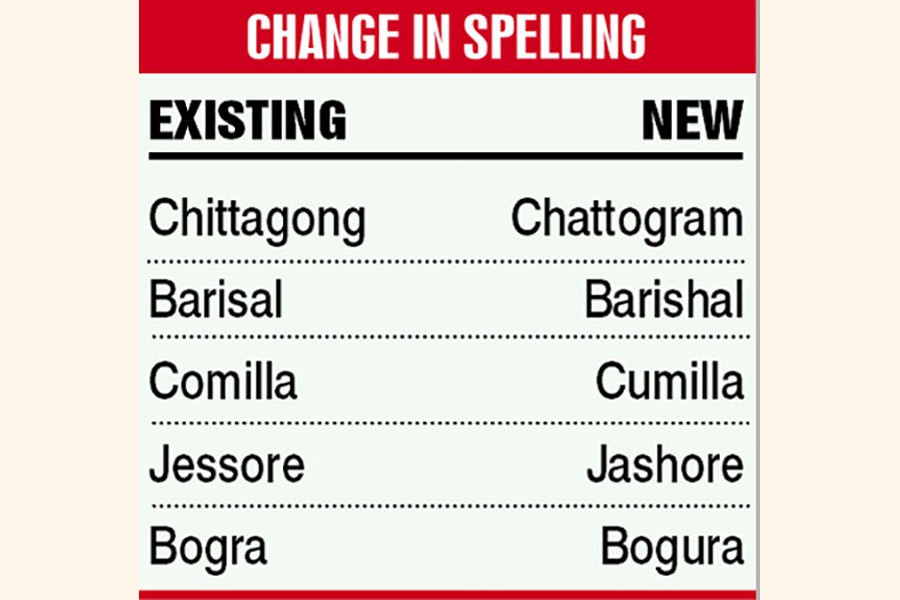

Whatever the public reaction is, the spellings of the names of five districts have been changed officially. More such changes are reportedly in the offing. The names are Chattogram (Chittagong), Cumilla (Comilla), Barishal (Barisal), Jashore (Jessore) and Bogura (Bogra). In terms of change, the new English spellings do not seem anything which might be called remarkably major. The catch is, no matter how close the English spelling of a local name could be brought to it, the pronunciation remains largely defective in the foreign tongue. In the 1980s, when 'Dacca' was made 'Dhaka', the name of the historic capital did not attain any special glory. The earlier name of the greater Comilla district was 'Tripura'. In English, it would be spelled as 'Tiperah'. The then Pakistan government changed the name into 'Comilla' in the mid-1950s, apparently to keep at bay the spectre of 'disintegration'. By the act it demonstrated its apprehensiveness over the dreaded closeness with the neighbouring Indian state of 'Parbottyo Tripura'. This over-reactive action also prompted the rulers to rename East Bengal (now Bangladesh) East Pakistan. They retained 'Punjab', despite the presence of another Punjab in India. All this was driven by myopic politics.

The trend of bringing changes to English spellings of Bangladesh place names, however, is one prompted by a kind of patriotic zeal. It can be likened to the return to pre-colonial native names of some countries in Africa. The three prominent among these changes are Burkina Faso (earlier Upper Volta), Zimbabwe (earlier southern Rhodesia) and Zambia (earlier northern Rhodesia). The changes brought to all the three were prompted by disillusionment with colonial rule, as well as the urge to uphold indigenous identities. Since the early 21st century many smaller regions and cities have been showing their desire to be known by their old names. In the sub-continent, 'Bombay' reverted to 'Mumbai', 'Madras' to 'Chennai' and 'Bangalore' to 'Bengaluru'. The Indian state of 'West Bengal' officially came to be known as 'Paschimbanga'. Its capital 'Calcutta' in English became 'Kolkata', which was closer to its Bangla pronunciation.

Even by not going into the debate over the gains or futilities of these changes, the new place names do carry some significance. Names and looks enable one to have a glimpse into the essence of something. Most importantly, these changes have a lot to do with feelings and certain emotions. The change of 'East Pakistan' into 'Bangladesh' involved the emotional welling-up of a nation and the irresistible urge to be free of bondage. Bringing spellings closer to those in the native language has a strong symbolic value. With a nation carrying the legacy of a colonial past, the spelling changes far transcend the precincts of rituality. Remaining content with the distortions left by a foreign power doesn't befit a nation with self-esteem. Changes to place names have been occurring since long. In the past they followed territorial conquests. The practice, nowadays, is set against a different perspective altogether.