To quote the Jibanananda Das, not everyone is a poet. Only a few of them are. Elaborately speaking, many people write poems. Only a small number of emerges as poets. Likewise, if someone carries or leaf through a book, he or she is not a reader. Few people see a true reader. They are not easy to identify in a vast book fair, like the one now being held at the sprawling Suhrawardy Udyan in Dhaka. The true readers dread frenzied book-lovers jostling around. They move mostly alone, engrossed in the world of their favourite books. Silently they move from one book stall to another, at times drawing ire of the sales people. They show no interest in the books the general people fall for. The books they frantically look for are not found in the stalls doing a brisk business. After a long search, the books may be available at a humbly decorated stall owned by a dying publication house.

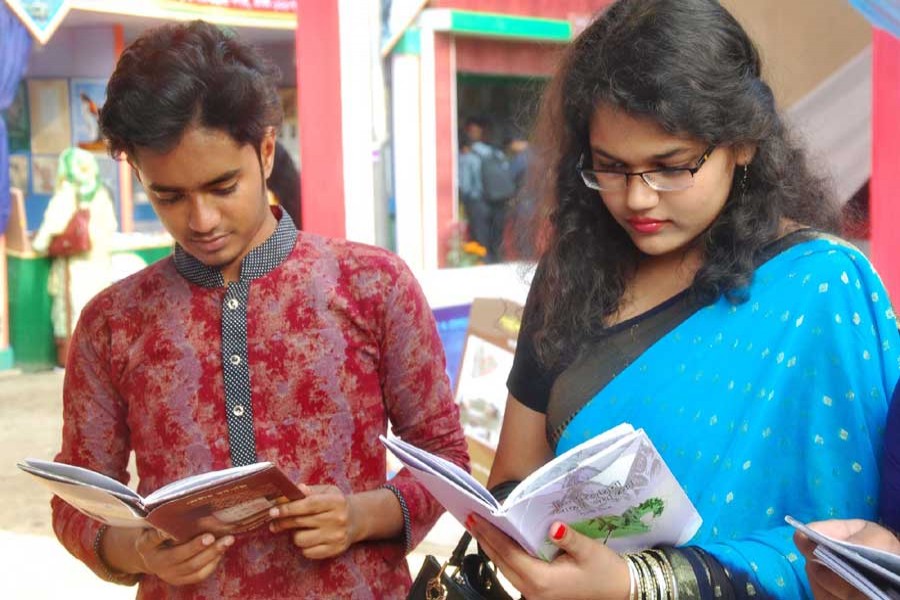

When these readers finally lay their hand on the book or the books of their choice, their delight knows no bound. It could be compared to the discovery of hidden treasures. As time wears on in this country, the number of genuine readers keeps dwindling. The large month-long book fair, like that organised by Bangla Academy on the eve of the Language Movement Day, once was a favourite hunt of these bookworms. They used to be normally seen at odd times moving amid the stalls, averting the many book-related events like book launches, autograph hunting or gossip sessions at one of the 'adda corners' set up by the organisers. Watching these self-absorbed readers at the fair ground, one is reminded of the event's old days. In those days, devoid of many book-related fun and entertainment, the fair premises would be filled with consummate readers only. The competition of bringing out new books had yet to become a dominant trend. Nowadays, the frenzied competition over the number of new publications between the younger writers detracts a lot from the seriousness that goes with books. Scores of readers rue the fact that books have become pure consumer items at the country's large fairs.

A striking aspect of the Ekushey Grantho Mela (Ekushey Book Fair) is how people visit the fair in droves to 'watch' books. Why should not they. Books at many stalls are not sold in their age-old formats. In a display of radical transformation in printing and publication styles, books reach the readers in attractive paper boxes. It is natural that these consumer items sold in the name of books do not have any appeal to the true readers.

The quintessential question is: who are readers and who are not. True readers never eagerly wait for book fairs. Every centre of books is a fair to them. Those could be a library, a book shop or an open-air footpath venue selling old books. The subconscious of a habitual reader remains filled with the urge to collect the books not read yet, as well as the recently published books. These books belong to the group of printed texts. Serious readers prefer them to the other mediums of publications. Of late, books began to be published online. They are getting popular with the relatively younger and emerging readers. But the readers passionately in love with books still shy away from online publications. However, with forecasts of the full-scale start of the era of online books, the old-style readers may not be able to keep themselves distanced from the digital publications for long. In the not-too-distant future when majority of the books are set to be published and read online, the lovers of print media might be compelled to turn to electronic books (E-books). Many overenthusiastic advocates of the digital publications have already begun watching old-style readers opt for E-books. The scenario may not fully reflect the reality. It's true the number of ICT-bred young bibliophiles has been on the rise. Still they are yet to outnumber the lovers of traditional printed books.

The new forms of any media are greeted with both caution and reservation. In the ancient times, just one or two hand-written books would be prepared for the readers. Those would make rounds among the readers by turn. This practice had been in place for long. With the start of mass production of books at printing presses, mostly dealing with anti-clericalism and the citizens' social views, the readers were said to have found themselves bewildered; they had never ever thought of this deluge of books containing these sensitive subjects. The scenario unfolded largely in Europe. Many of the readers allegedly refrained from procuring the books. They feared the mass production of these books could be a strategy to identify the dissenting elements in a kingdom. However, in a decade or so all these premonitions had disappeared. Printing presses began mushrooming throughout the world with the book publication sector undergoing a radical transformation. Procuring books online, has, amazingly, sparked a similar foreboding, especially for people in countries witnessing abuse of the online media.

In spite of the newer modes of publication and the related complexities surrounding books, genuine readers keep themselves glued to printed publications around the world. The approaching era of E-books notwithstanding, printed books still dominate the publication world. In the large cities of the advanced countries with a mindboggling and developed ICT industry, book shops filled with hardbound and paperback publications are a common sight. However, these shops also have digital corners selling books in the CD form. Bangladesh book stores and libraries are still filled with traditional paper books. These are the places, where the readers pass their time the most intimate and comfortable way.

Readers advocating printed books offer a few reasons for their feeling at ease with traditional publications. One of them, undoubtedly, is a potent one. It is the readers' tangible contact with books while reading them. In going through an E-book, a reader can also turn a page. All he or she is required to do is press a key on the keyboard of computers. Readers can complete reading a book without coming into contact with any piece of paper. Many E-generation youths are seen nowadays reading a voluminous book overnight on the PC or smart phone screen. The activity could be compared with watching a movie. True readers cannot think of this virtual or sham reading. Unless they touch a book, carefully turn its pages or place a marker on a certain page and start reading the book again, the ritual of reading remains incomplete. No matter what kind of hurdles stand in their way, none will be able to resist the avid readers from collecting a printed book --- at least not in the near future.

At this point a critical task may crop up involving the people related to selection of manuscripts, printing and, finally, marketing. Selections are mostly done by the publishers, unless a writer takes his or her own initiative to bring out a certain book. Fewer people are required for taking E-books to the readers. The digital sector is free of the cumbersome stages the manually produced books ought to go through. Moreover, the E-books are free of the scourge of getting worn out with the passage of time. They can't be stolen and borrowed, and not returned back. With so many advantages offered by digital books, why people remain stuck to traditional books is a great quandary. The amazing reality is despite its many drawbacks, the country can still take pride in its growing readers. It matters little whether they are digitally oriented or not. But they do serve the authors as their genuine patrons by purchasing their books; vast numbers of them are still printed on paper. It is the readers who help the authors survive. At the same time, it is the critics' responsibility to create the urge for good books among the general readers. A number of scholars differ on this point. As they view it, readers are born --- many with the passion for good books. They cannot be created.