The governments of Bangladesh and India have agreed to sign a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA). Formal announcement in this regard was made in the last week of September this year in Dhaka. Commerce ministers of both countries expressed high hopes on the outcome of the agreement, little details of which have been made public. Thus the issue deserves close scrutiny, especially in the perspective of bilateral connectivity which has gained momentum in recent times.

The proposal of CEPA was formally mooted by India early this year and Bangladesh accepted it within a short time. However, a number of Indian experts floated a similar idea a few years back under the so-called Track-II diplomacy framework. It failed to draw much attention at that time.

CEPA would be a free trade deal on goods and services along with mutual facilitation on investment. It would also include provisions of cooperation or partnership on trade and customs facilitation, competition and intellectual property rights (IPRs) between the contracting countries. Thus, it would be wider in scope than the traditional Free Trade Agreements (FTAs).

Bangladesh is yet to sign any FTA with any country though a number of initiatives have been taken. It was in 2003, when India asked Bangladesh to sign bilateral FTA and Bangladesh agreed to start negotiation in 2008. But there was very little progress. In 2011, India allowed tariff-free market access, in compliance of WTO regulations, to all but 25 Bangladeshi products under the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) agreement. Thus the need for BFTA was to some extent materialised.

Nevertheless, geo-political tension mostly originating from Indo-Pak rivalry put the future of SAFTA under question. The bilateral hostility reached to a new peak in 2016 when India had boycotted the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) summit citing Pakistan's unrelenting support to terrorist activities in India. Bhutan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan had also expressed their inability, although on different grounds, to attend the summit. At the same time, India put some additional effort to move ahead with the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan are common members of both the regional blocs while two other members of BIMSTEC are Myanmar and Thailand.

CONNECTIVITY IN FOCUS: Meantime, India has reinvigorated its efforts to strengthen connectivity with Bangladesh both through bilateral and sub-regional frameworks. Due to some geo-political implications, full-fledged transit and transhipment facilities to India thorough Bangladesh ultimately got packaged with a number of sub-regional moves like Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal (BBIN) Motor Vehicle Agreement (MVA). But a big push to widen bilateral connectivity has been there for the last couple of months. As a result, the two countries have signed a number of agreements in the last week of October in New Delhi.

One agreement allows India to use Chattogram and Mongla sea ports for transhipment of Indian goods to its land-locked North-Eastern region. It is a landmark move especially for India as the country has long been waiting to get port access. For Bangladesh, it is very challenging as sharing the sea ports is likely to put pressure on its own international trade.

In another agreement, Dhaka and Delhi also decided to initiate Kolkata-Dhaka-Guwahati-Jorhat river cruise services. The two countries have also decided to increase the river routes and ports of call under the existing Protocol on Inland Water Transit and Trade (PIWTT). Port of call is a spot where ships make a stop during a journey.

The third agreement allows inclusion of Rupnarayan river from Geonkhali to Kolaghat in West Bengal in the protocol route. They also agreed to declare Kolaghat in West Bengal and Chilmari in Bangladesh as new ports of call. Again, both parties agreed to declare Badarpur on river Barak as an extended port of call of Karimganj in Assam. Ghorasal of Narsingdi is selected as the extended port of call for Ashuganj in Bangladesh.

It is very crucial for India to enhance connectivity with the north-eastern region through Bangladeshi inland waterways. It has already outlined a detailed plan for establishing 900-km 'waterway freight corridor' through Bangladesh to reach north-eastern states. The waterway may reduce the cost of carrying goods by about 70 per cent. India has already agreed to finance 80 per cent of the dredging cost of Ashuganj-Zakiganj and Sirajganj-Daikhowa stretches of Indo-Bangla inland water protocol route. The extensive dredging will allow smooth movement of water cargos in dry season.

Finally, in the Delhi meeting, India restated its proposal to use Kolkata and Haldia ports for transhipment of Bangladeshi goods in bilateral trade. It also asked Bangladesh to give opinion on 'third country' export-import trade under coastal shipping agreement. Bangladesh, however, said that it would hold stakeholder consultations in this regard first. Stakeholders in Bangladesh are yet to understand the rapid development in water-based connectivity adequately. Same thing is also true for CEPA.

CEPA REQUIRES EXAMINATION: The proposed Indo-Bangla CEPA will take more time to negotiate due to its complex nature. Very little background work has been done, although the Indian side has already sent a draft in this regard. It seems unusual as the government generally goes for a study before taking any decision on any bilateral or regional trade-related issues. Nevertheless, a detailed study can still be done before initiating negotiations on CEPA.

India has already signed two separate CEPAs with Japan and South Korea and three Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreements (CECAs) with Malaysia, Singapore and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). All these are now in force. Moreover, India and Sri Lanka have also negotiated a similar deal but not finalised as yet. Outcome of these deals are still inconclusive.

Both the CECA and CEPA are almost similar as there is no rigid criterion for these. Negotiating countries can customise their own CECA or CEPA. Some argue that technically CECA is mostly an extension of bilateral FTA and it should be singed first before going for CEPA. Some other counties in Asia and the Pacific region also have similar agreements. Australia and Indonesia finalised their bilateral CEPA this September.

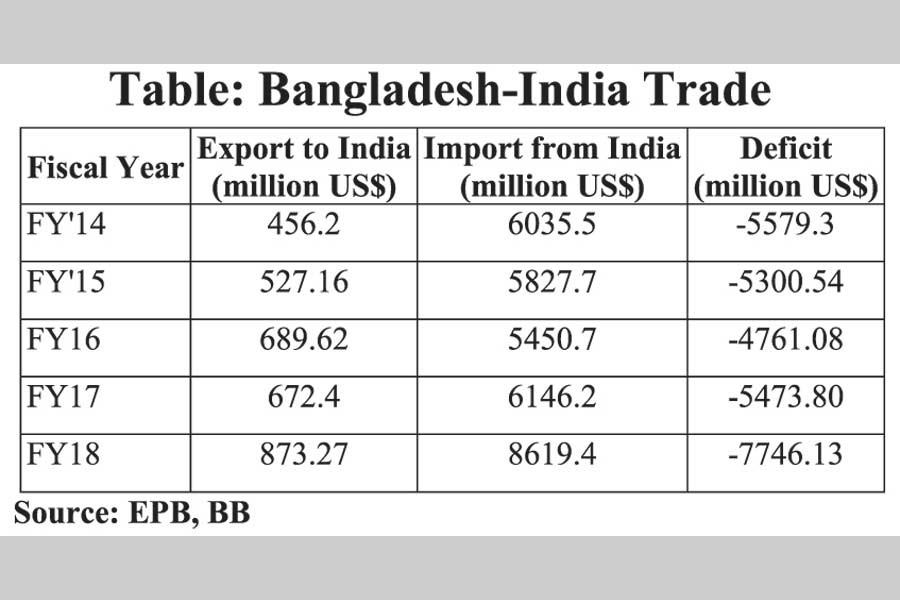

Having huge deficits in bilateral trade in goods and services with India, the proposed CEPA is unlikely to create any win-win situation initially. The bilateral merchandise trade gap stood at $7.74 billion in the past fiscal year (FY18). Though export to India soared by around 30 per cent to $ 873.27 million in the past fiscal year from $672.40 million, merchandise import from India recorded 40 per cent growth during the period under review. As a result, payments for import from India stood $8620 million in FY18 from $6146.20 million in FY17. Deficit in service trade also reached at around $630 million as earnings from service export is negligible ($0.61 million).

As India is the third largest trading partner of Bangladesh mainly due to its being the second largest source of import, deepening of economic integration through trade and investment is a must. The decision to strike CEPA appears sensible although there are factors that may not render it win-win. Due to the gap between the level of economic development along with disproportionate size of two economies, Bangladesh is not in a position to provide reciprocity to India under the proposed agreement. The country has also no legal obligation under the framework of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Graduation from the Least Developed Country (LDC) status by 2024 will also not bar to enjoy existing preferential trade benefits for another three years. All these things need to be taken into consideration while negotiating CEPA with India.