Bangladesh economy has been registering a consistent upward growth for the last few years. At the same time, inflation rate has also been maintaining a modest hike. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rose to 7.86 per cent in the past fiscal year (FY18) from 6.03 per cent in FY13. Annual average inflation rate, calculated on the basis of consumer price index, declined to 5.78 per cent in the past fiscal year from 6.78 per cent recorded six years back.

Thus the country virtually enters into the 'high-growth low-inflation' cycle. This is a comfort zone for policymakers and also a 'great achievement' for the government as long as the distribution aspect of growth is kept aside.

But it is unwise to focus on growth only without looking into distribution. It is also not possible to see the actual benefit of lower inflation without knowing the situation of real wage. Again, wage trend also reflects a pattern of growth distribution. So, there is an interlinking between growth, inflation and wage. Thus the strength of 'high-growth low-inflation' achievement may be tested by reviewing the linkage.

The 'Global Wage Report 2018/19', prepared and released by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) last month, focused on global trend of real and nominal wage growth and identified that real wage growth declined to 1.8 per cent in 2017 from 2.4 per cent in 2016 globally. Moreover, the rate fell to its lowest since 2008 -- far below the levels obtaining before the global financial crisis.

The scenario in Bangladesh is similar to the global trend. The real wage registered only 3.0 per cent growth in the past year which was 3.60 per cent in 2016. The country witnessed 3.4 per cent average growth in real wage during the last one decade (2008-17) which was lower than the Southern Asia's growth rate of 3.7 per cent during the period. In the region, India achieved the highest growth rate of 5.5 per cent in real wage, followed by Nepal (4.7 per cent) and Sri Lanka (4.0 per cent). Pakistan (1.80 per cent) and Iran (0.40 per cent), however, achieved very low growth in real wage in the region.

If considered in the long-run (2000-2017), real wage in Bangladesh registered the lowest growth on an average among the countries, as per ILO report. The rate was 3.0 per cent against 5.0 per cent in Nepal, 5.50 per cent in India, 6.30 per cent in Sri Lanka, 8.90 per cent in Pakistan and 7.50 per cent in Iran.

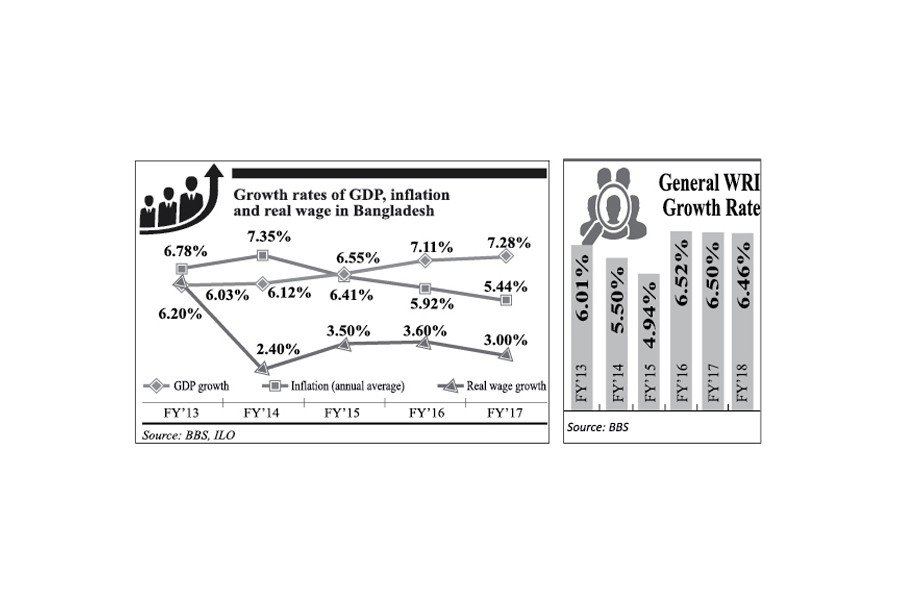

Thus Bangladesh is not doing well in terms of real wage growth. What is more striking is sharp decline in the rate of real wage growth in a period when GDP growth was upward and inflation was in lower curve (see Chart).

Real wage is basically the net of consumer price inflation which means nominal wage is deflated by the consumer price index (CPI). By adjusting nominal wage in terms of inflation, real wage can be determined and so it is also known as inflation-adjusted wage.

Having low level of inflation in recent period, the low growth in real wage is actually ominous for Bangladesh. It means increase of nominal wage in the country is so small that even low inflation is largely eating up the modest rise in nominal pay.

Nominal pay or wage is the amount of money a worker receives from his/her employer. The Wage Rate Index (WRI), estimated and published by Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) monthly, is a good yardstick of the nominal wage. The WRI, however, doesn't count 'salary paid and high contract based earnings' to calculate the index. Nevertheless, it shows the trend of nominal wages of 'low paid skilled and unskilled labour' over time in different sectors of the economy.

The WRI (see graph) show that growth rate of nominal wage in the country has been fluctuating since FY13 when it registered 6.01 per cent growth. The rate declined to 5.50 per cent in FY14 and 4.94 per cent in FY15. After rebounding sharply to 6.52 per cent in FY16, it again declined to 6.50 per cent in FY17 and 6.46 per cent in FY18.

It thus shows that the growth of nominal wage is not growing adequately at par with the GDP growth rate which crossed 7.0 per cent mark in FY16. Though GDP posted 7-plus growth in the past three fiscal years (and every time higher than the previous year), nominal wage growth declined gradually.

The latest adjustment of the minimum wage structure of the readymade garment (RMG) industry workers may also explain the lower growth of real wage. Though the industry owners are highlighting 51 per cent hike in the minimum wage as a 'big blow to the industry,' the reality is different. If adjusted with inflation, the actual hike in the minimum wage stands at around 20 per cent (taking 32 per cent combined inflation rate in five years into consideration). Again, the hike takes place after five years and so annual average rate of wage hike is only 4.0 per cent. Growth rate of real wage is evidently lower compared to GDP growth.

Lower growth of real wage indicates a decline in the bargaining power of workers. Though it is now a global phenomenon, in Bangladesh it has been declining rapidly for the last two decades. Too much politicisation of trade union activity coupled with discriminatory labour laws and polices push the decline. This fallout has also been weakening the share of labour compensation in GDP.

This leads to uneven growth distribution in Bangladesh with wealth being accumulated in a fewer hands. A number of socio-economic indicators suggest that growth story of Bangladesh is also a story of rising inequality and social disparity. Policymakers appear indifferent in this regard. Some of them also argue that disparity is unavoidable for the time being especially when an economy is at its take-off stage.

However, equitable distribution of growth doesn't mean equal share of the growth pie for every one. It is rather ensuring due and right shares of everyone from the economic growth through both market mechanism and state intervention. If nominal as well as real wage do not increase adequately, a large number of working-class people are compelled to contain their consumption spending. This suppresses demand and puts a brake on the optimum growth of the economy.