In 2017, I arrived at Kabul's Hamid Karzai Airport as part of a congressional staff delegation. Even though the United States (US) embassy stood a mere four miles away, safety concerns necessitated our helicoptering from a recently constructed multimillion-dollar transit facility instead of traveling by road. As we flew over Kabul, I realised that the Afghan security forces, backed by thousands of US personnel, could not even secure the heart of Afghanistan's capital.

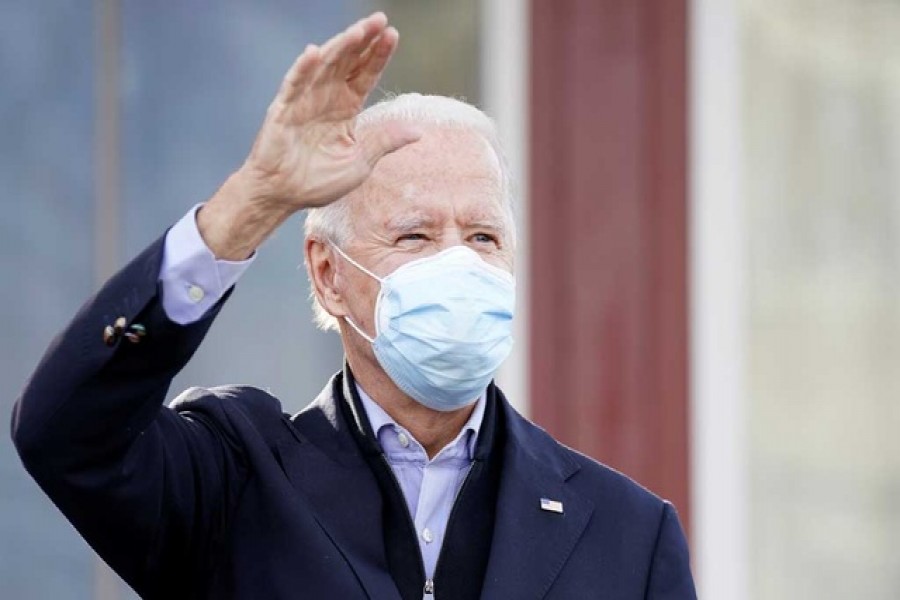

Kabul was not lost yesterday; the United States and our Afghan partners never truly had control of the country, nor of its capital. Once the Taliban had secured an agreement that the United States would be pulling out and that forces would be reduced to minimal numbers before Joe Biden's presidency began, they merely had to wait.

The dozens of congressional briefings I attended over 14 years of working on Capitol Hill underscored this dynamic. The intelligence community would commence each briefing with a stark assessment regarding the fragility of conditions in Afghanistan. Senior defence leaders would then provide a far more optimistic view, one that often gave a sense of progress, despite the Herculean challenge with which they had been tasked.

Various critics of President Biden are engaging in fantasies amid Kabul's collapse: if only we'd used more force, demonstrated more will, stayed a few months longer, and then the Taliban would have adopted a different strategy. John Allen, a retired Marine general and former commander of forces in Afghanistan, argued last week that Biden "should issue a public redline" and that "just this announcement will help the Afghan government and give the Taliban pause." Ryan Crocker, a former ambassador to Afghanistan, was sharply critical of the withdrawal of the last 3,500 troops. Fred Kagan, of the American Enterprise Institute, argued that "keeping American military forces in Afghanistan indefinitely" would be "worth it."

These criticisms ignore the developments of the past decade and downplay the impact of last May's announcement. Even the Biden administration's harshest detractors mostly concede that the United States would eventually have had to withdraw from Afghanistan. According to the US military, the Taliban was stronger this year than it had been since 2001, while the Afghan defence forces were suffering from high rates of attrition. At some point, the attack on the Afghan government would have come, and US troops would have been caught in the middle-leaving the U.S. to decide between surging thousands of troops or withdrawal.

Some critics also argue that the United States should have preserved a residual force in Afghanistan, much as we have in South Korea. There are any number of ungoverned spaces today, however, which pose as great a threat, if not greater, to US security as Afghanistan, and few are calling for US deployments to those areas. There is a cost-financial and military-to tying forces down in a project that was ultimately doomed to fail.

Finally, critics are lobbing the usual refrain that the withdrawal has damaged US credibility. "Afghanistan's Unraveling May Strike Another Blow to U.S. Credibility," read a headline in The New York Times; "Afghanistan's Collapse Leaves Allies Questioning U.S. Resolve on Other Fronts," echoed The Washington Post. The United States has spent billions of taxpayer dollars, fought for more than 20 years, and suffered thousands of casualties in this war. If that sort of commitment lacks credibility, our allies will never believe we are doing enough. Critics likewise argued that withdrawal from Vietnam would hurt our credibility. In reality, Japan and other allies questioned our ability to protect them not because we withdrew from Vietnam, but because the United States was militarily overstretched. Withdrawal did not undermine our credibility; by consolidating our efforts, it might enhance it.

The United States had multiple opportunities over the past 20 years to pursue an end to its involvement in Afghanistan. Shortly after the initial invasion, the US rejected a reported offer of surrender. In 2011, peace negotiations were suffocated in their infancy by political opponents and a wary Pentagon. President Biden has demonstrated courage in finding a path forward where others merely fought to preserve the status quo.

Now policy makers should focus on mitigating the fallout of this disaster. First, Congress-led by advocates such as Representatives Jason Crow and Seth Moulton-should redouble its efforts to allow for the immigration of vulnerable Afghans.

Second, Congress and the administration should revitalise engagement with Pakistan and our regional partners in order to contain the fallout from Afghanistan. Pakistani leaders rebuffed both the Bush and Obama administrations' efforts to cooperate on counterterrorism and instead played a dangerous double game, providing succour to terror groups like the Haqqani Network while accepting billions as part of our counterterror effort. US officials should approach Pakistan in a bluntly transactional manner by asking its leaders to assess the cost of preventing terror groups from using its borderlands as a refuge.

Finally, the United States should repurpose the international-coalition framework used during combat operations in Afghanistan, turning it into the basis of a sustained diplomatic mission. The coalition should keep eyes on the ground in Afghanistan, engaging with Taliban officials where appropriate. This will be challenging without military forces in the country, but it is not impossible, and even a minimal level of observation would be better than the neglect we chose after 1995. The coalition should also collaborate on measures to encourage the Taliban to prevent its territory from being used as a launching point for terrorist attacks. Last, the coalition should maintain UN-based sanctions on the Taliban to pressure the new government to preserve the rights of women and minorities, including the Shiite Hazara population.

Biden faced a set of bad options. He ultimately made the difficult but necessary choice to preserve American lives. That decision will have devastating consequences for Afghanistan, and we will learn more in the coming days regarding how the administration might have executed its plans better. But as I saw for myself in 2017, and as many others had also observed, the government we supported never truly controlled the country it governed. Biden did not decide to withdraw so much as he chose to acknowledge a long-festering reality, one accelerated by the previous administration's withdrawal announcement.

Daniel Silverberg is a former Department of Defense official and, until recently, the national security adviser to the House majority leader. Excerpted from The Atlantic.