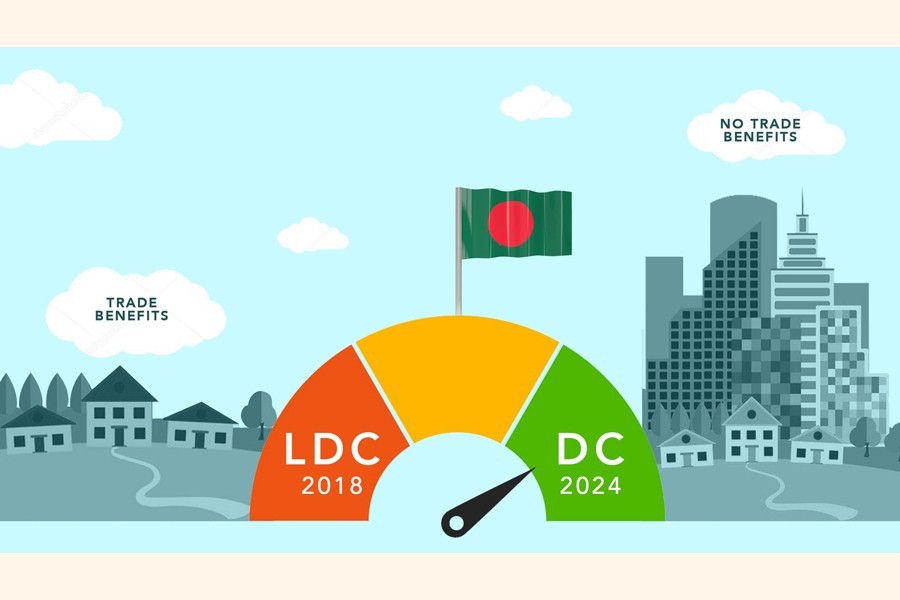

It must have been a rendezvous of destiny when two U.N. agencies found Bangladesh on the aspirant list. One was the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), whose Committee for Development Policy (CDP) monitors development-based 'graduation', in our case from a 'Least Developed Country' (LDC) to a 'developing' one from 2026. The other is the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, whose Division of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) monitors what the title itself says. This one traces its origin to Agenda 21 in the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit of 1992. By September 2015 both U.N. institutions became top Bangladesh priorities. That partnership shows a realistically mixed scorecard today, yet the future could become grimmer.

All this was against a background of a global community too reckless to acknowledge the damage being wrought by conscious development plans. Or, as post-World War-II newly-independent countries were too oblivious of how chipped a world they had entered after getting their freedom. Every country on the upswing of both developmental and sustainable fronts has a right to believe the post-1992 scripts were written for them, partly to alleviate the strategic environmental losses caused by industrialisation and carbon emission in the century before, and partly to assume the 'developing country' mantle created for them. Bangladesh was no exception: it had just broken free from military rule, was already riding high on both microfinance and RMG (ready-made garments) economic miracles, and by 2015 ready to sail higher on both fronts.

Neither the country's LDC 'graduation' pathway nor the 17 SDG mandates were lined with red-carpets, yet Bangladesh has no choice but to make both missions rewarding. Its progressive 'graduation', like other countries on that list, cannot but be aligned with its SDG crusade if success is sought. Today's SDG theme accents the very first term of the label: sustainability. Five goals directly addressing that (SDG 11-SDG 15) pose the most stringent of tasks for a country among the world's most vulnerable against both environmental threats and climate-change impacts.

SDG 11 is on 'sustainable cities and communities', SDG 12 on 'responsible consumption and production', SDG 13 on 'climate change', SDG 14 on 'life below water', and SDG 15 on 'life on land'. Each is one of the most sensitive human concerns today. Currently, Bangladesh is the 104th-ranked country, out of 163, in the SDG Index (a progress report). No DC (developed country) aspirant can rank or remain so low, and no LDC can 'graduate' without showing progressive signs with this rank. As of 2022, the Sustainable Development Report shows SDG 12 and SDG 13 have been achieved by Bangladesh, but all the others pose major challenges: SDG 11 is moderately improving; SDG 14 remains unchanged; but SDG 15 is deteriorating.

SDG 11 does not inspire to know how the country's capital has become one of the world's most congested, polluted, and filth-filled metropolitan area. How Bangladesh moved from a famine-hit agrarian backwater to knocking on the door of the world's top-forty economies is good SDG news. Bangladesh's capital Dhaka partly explains why SDG 13 is ahead of the game. Yet why materialism undermines both SDG 14 and SDG 15 helps explain why Dhaka has become a colony of artless high-rise buildings and the Bay of Bengal is being turned into a possible El Dorado with dreams of 'black gold' (that is, petroleum). Ultimately material gains will have to fight it out with sustainability pressures, with the winner determining the country's future.

Turning the material mindset into a conservation-driven resource is not likely of today's generation. Yet Dhaka is unlikely to persist much longer without resuscitation: groundwater is diminishing, all its rivers have high toxic levels, some irretrievably so, while profit-making through rental apartments in high-rise buildings or factory-ownership continue to top any average citizen's agenda. With megaprojects designed to ease congestion and accelerate transportation flows may end up attracting more rural dwellers into the crowded metropolis in the short-run, when it must be galvanising itself to deliver SDG imperatives. How the post-pandemic inflation circumscribed jobs and expenditures cannot but push more unemployed people from the countryside into the cities.

Dhaka symbolises Bangladesh's metropolitans. None other is quite the size of Dhaka, but they all experience congestion, unplanned construction, and face the dire shortages of critical infrastructures. All of these show unfolding reforms, but the faster-paced 'graduation' pathway imposes a quicker timeline. This may be too quick to digest each megaproject's goals or acclimate citizens to their proper usages. Nothing short of a miracle can bail Bangladesh out, especially as megaproject allurements also throw a curveball: does completing the Padma Bridge, for example, mean more automobiles plying the highways before pollution-controlling laws get enacted? Anticipatory action helps by softening the developmental change or climate-related impacts.

These megaprojects could become the Achilles Heel of advancing the country, the more so the more replicated they become. Though a success story, 'responsible consumption and production' (SDG 12) also seems set to unravel in an unplanned way, unleashing brinkmanship: unless an emergency strikes, no one wants to do anything about medical problems; but deteriorating health pushes consumers abroad, to Bangkok, Kolkata, or Singapore, an unassailable decision no doubt, but whose long-term consequences include retarding local growth and institutionalisation. Production is a game we play very well, whether it is food in the farms or RMG factory outputs. Yet a 'responsible' level is absent, suggesting another arena needing attention. Since curbing consumption and production is vitally needed at a more mature developmental stage, learning and practising this art becomes a long-term investment.

Climate-change impacts (SDG 13) threaten us most. Bangladesh's coastline, Chattogram Hill Tracts (CHT), Sundarbans Forest, and receding river-banks (from erosion, toxicity, and upstream diversion/local consumption), demand attention. Our protective efforts may not be idle on these fronts, but they certainly do not match the needs of the day: refugee inhabited Kutupalong faces land erosion; elsewhere on CHT lands, we see uncurbed deforestation, ostensibly in the name of development, such as building highways, hotels, leisure resorts, and so forth; Sundarbans forest met it match in the rivers drying up, salt-water creeping in as replacement, and cattle-ranchers chopping off trees here or there for pastureland; and receding river-banks pose more direct threats to more people than any of the other climate-change effect.

Trees, indeed, may be our final and most accurate SDG measurement, and predictor of how pretty we look as a 'developing' country. Bangladesh falls slightly short of the 18 per cent of land area forests must cover, but since in 2020 that figure was just under 15 per cent, hope is in the air. If extravagance and recklessness can be controlled there, a greener future Bangladesh awaits us.

Dr Imtiaz A Hussain is Professor, Global Studies & Governance Department, Independent University, Bangladesh.

[email protected]