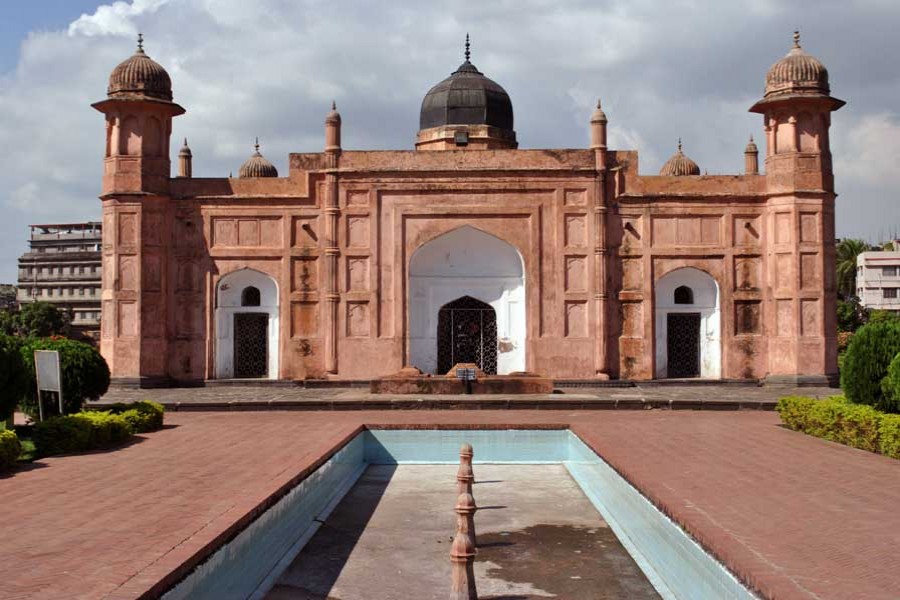

Had there been no British administration, though colonial, Dhaka's Lalbagh Fort and its other landmark relics would have crumbled down one-and-half to two centuries ago. In their place the city residents would have seen the construction of different types of new-age architectural edifices. As time wore on, these buildings were supposed to see newer renovations befitting taste and trends of the time. Thanks to British passion for the preservation of installations carrying heritage value, Lalbagh and other set-ups have been able to save themselves from the sledge hammers of labourers employed by the later-generation developers. The post-partition Pakistan also did not show the dreaded temerity to demolish buildings and installations of archaeological importance. As they had left Mohenjodaro and Harappa undisturbed, they did not think of tampering with Mahasthangarh ruins or majestic temples like Kantajeu Mandir in Dinajpur.

It's saddening to note the short shift given by the authorities to scores of archaeological sites in independent Bangladesh. Lots of historical edifices built in medieval and earlier periods in Bengal failed to save themselves from the onslaughts of man --- euphemistically termed time. While they were being encroached upon or destroyed, the government agencies looked the other way. Those brick-built constructions included palatial mansions and chateaus, royal courts, ramparts, prayer complexes etc. The reason archaeologists have cited for their eventual disappearance chiefly comprises triumphalism on the part of a conquering king or a local feudal chief. The local influential land grabbers also did not lag behind. As part of the human nature, upon conquest of a land, many triumphant heroes demolish the vestiges of the previous rulers. They do not feel any emotional attachment to the architectural marvels of the time before them. Perhaps in line with this rule, numerous historical structures are found in the forms of ruins in the later years. This applies to many territories and civilisations around the world.

In almost every land, the once-majestic concrete structures become pitifully dilapidated through the ages, because cruel time continues to chip away at their past elegance and grandeur. In Bangladesh, the vulnerably standing sites of Mahasthangarh and Paharpur Buddhist Monastery are two such victims of neglect. At Mahasthangarh, bricks made in ancient times continue to be stolen; exclusively archaeological plots are made private properties with unauthorised structures being erected on its peripheries. Unchecked littering and noise by tourists increasingly robs Paharpur of its serenity. Many also add the name of Shaalbana Buddhist Monastery in Lalmai-Mainamati area to the list. The list gets longer as excavations continue to be carried out by dedicated batches of young archaeologists. Over the last three decades, nearly a hundred worn-out structures have been discovered and marked 'archaeologically important' across the country. They include temples, mosques, lost townships, ports etc. Of them, Wari-Bateshwar human settlement in Narsingdi, not far from Dhaka city, stands out with its amazing archaeological prospects.

Good news is, a few renovated historical spots in the country have found place on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Prominent among them are Shatgombuj Mosque in Bagerhat district and Paharpur Monastery in Jaipurhat district. A number of other sites are mulled as prospective candidates for UNESCO recognition. There is a bleak aspect of the future UNESCO heritage sites list: due to their ill maintenance a number of the heritage sites may not make it to the said list despite their great archaeological potential. Moreover, a few are feared to lose their titles eventually. However, the discoveries increasingly prove that this small deltaic country ruled by different dynasties is in fact a treasure-trove of invaluable ruins. Apart from kingly sites, there are a lot made famous for their ancient links to religious practices. Many early royal sites had been made to fall into ruin due to neglectful stance on them by the latter kingdoms. On the other hand, the religious centres were spared these spiteful treatments. According to historians, it has a lot to do with the tolerant attitude of religious groups to each other in the land's distant past. Instances of causing wholesale damages to places of worship by apparently antagonistic communities, except during brief interludes, are little in the land of Bengal. This has helped greatly its architectural heritage flourish. Proofs of simultaneous construction of mosques and temples side by side are plenty. In cases, the same groups of building planners and masons may have been employed to construct separate structures. Later animosities, provoked by vested interests, have drawn the curtain over this chapter effusing fraternity and social harmony.

These apart, architectural wonders are encountered in the private individual sectors too. Apart from the ruins of institutions, community places and other installations built by the locals of an area, there are many such installations constructed and promoted by local 'zemindars' or representatives of Delhi-based rulers. Mosques comprise a grater segment of these aesthetically built installations. The Bengal Sultanate and the Mughal periods are credited with building many such places of saying prayers. But in spite of their architectural magnificence, those have fallen on hard time thanks mainly to the negligent attitude towards them by the later state administrations. The Rezakhoda Mosque in a Bagerhat village is one such structure. Built in the 15th century, and now lying in a completely time-worn state, the mosque is under the custody of the Department of Archaeology. It is said to have been declared a UNESCO World Heritage in 1985. Due to its being unfit for saying prayers inside, a section of local enthusiasts has built a tin-roofed building adjacent to the dilapidated mosque. They have also made use of some of the pillars of the mosque's ruins. Now a dilemmatic situation has emerged. Relevant laws do not permit anyone to renovate an archaeological site, like Bagerhat's 15th century mosque, at one's own sweet will. But the worshippers cannot use the new makeshift mosque either, as the structure has many construction deficiencies. The onus, however, is with the department concerned. According to UNESCO, the Department of Archaeology should ensure that activities which may affect the Outstanding Universal Value of the property --- such as buildings or infrastructure, cannot be carried out within or close to the property and no one can alter or deface monuments.

This is but one example of how an archaeological monument from the ancient times enters the process of decay, and finally, disappearance in this country. Like mosques, a number of once-famous Hindu temples are also said to be bracing for meeting similar fate. Due to the land's being inhabited by the people belonging to Hindu belief and popular cultures before the arrival of Islam, temples were found to be scattered everywhere. Many of them later emerged as landmark structures of architectural exquisiteness. A few have survived the ravages of time only to keep themselves erect amid a mist of obscurity. The stark reality is the structural plight of temples in remote areas is similar to many ancient mosques. It is mainly the common people who take it upon themselves to keep the places of worship alive by visiting the places regularly even today.

There is also another aspect of this matter. As seen in Bangladesh and other poorer countries, it is only the educated enlightened classes which attach value to the preservation of archaeological sites. The general people are least bothered about their protection. The scene is different in the developed societies. Here, every citizen is equally concerned about a threatened structure.