The spin is all too predictable. With the US stock market clawing its way back from the sharp correction of early February, the mindless mantra of the great bull market has returned. The recent correction is now being characterised as a fleeting aberration - a volatility shock - in what is still deemed to be a very accommodating investment climate. After all, the argument goes, economic fundamentals - not just in the United States, but worldwide - haven't been this good in a long, long time.

But are the fundamentals really that sound? For a US economy that has a razor-thin cushion of saving, nothing could be further from the truth. America's net national saving rate - the sum of saving by businesses, households, and the government sector - stood at just 2.1 per cent of national income in the third quarter of 2017. That is only one-third the 6.3 per cent average that prevailed in the final three decades of the twentieth century.

It is important to think about saving in "net" terms, which excludes the depreciation of obsolete or worn-out capacity in order to assess how much the economy is putting aside to fund the expansion of productive capacity. Net saving represents today's investment in the future, and the bottom line for America is that it is saving next to nothing.

Alas, the story doesn't end there. To finance consumption and growth, the US borrows surplus saving from abroad to compensate for the domestic shortfall. All that borrowing implies a large balance-of-payments deficit with the rest of the world, which spawns an equally large trade deficit. While President Donald Trump's administration is hardly responsible for this sad state of affairs, its policies are about to make a tough situation far worse.

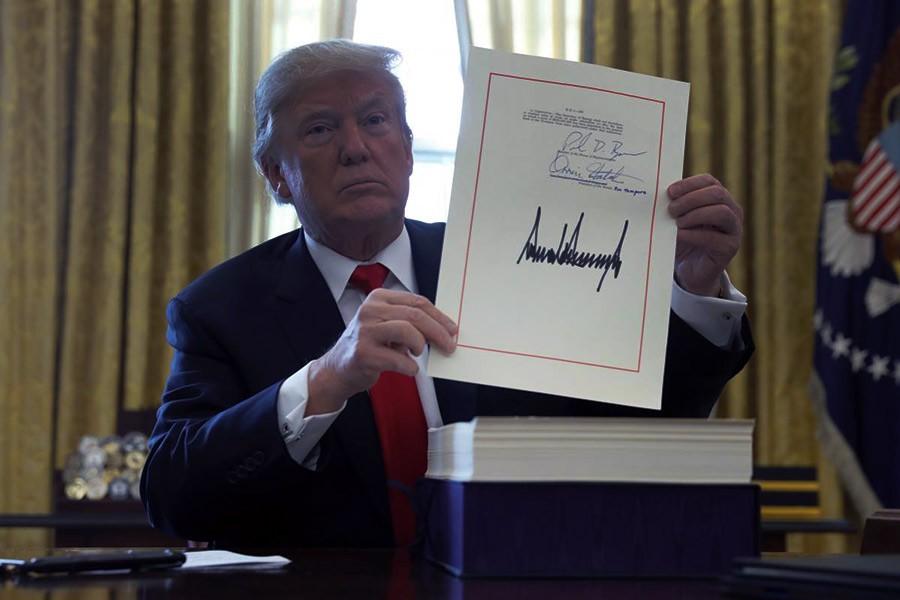

Under the guise of tax reform, late last year Trump signed legislation that will increase the federal budget deficit by $1.5 trillion over the next decade. And now the US Congress, in its infinite wisdom, has upped the ante by another $300 billion in the latest deal to avert a government shutdown. Never mind that deficit spending makes no sense when the economy is nearing full employment: this sharp widening of the federal deficit is enough, by itself, to push the already-low net national saving rate toward zero. And it's not just the government's red ink that is so troublesome. The personal saving rate fell to 2.4 per cent of disposable (after-tax) income in December 2017, the lowest in 12 years and only about a quarter of the 9.3 per cent average that prevailed over the final three decades of the twentieth century.

As domestic saving plunges, the US has two options - a reduction in investment and the economic growth it supports, or increased borrowing of surplus saving from abroad. Over the past 35 years, America has consistently opted for the latter, running balance-of-payments deficits every year since 1982 (with a minor exception in 1991, reflecting foreign contributions for US military expenses in the Gulf War). With these deficits, of course, come equally chronic trade deficits with a broad cross-section of America's foreign partners. Astonishingly, in 2017, the US ran trade deficits with 102 countries.

The multilateral foreign-trade deficits of a saving-short US economy set the stage for perhaps the most egregious policy blunder being committed by the Trump administration: a shift toward protectionism. Further compression of an already-weak domestic saving position spells growing current-account and trade deficits - a fundamental axiom of macroeconomics that the US never seems to appreciate.

Attempting to solve a multilateral imbalance with bilateral tariffs directed mainly at China, such as those just imposed on solar panels and washing machines in January, doesn't add up. And, given the growing likelihood of additional trade barriers - as suggested by the US Commerce Department's recent recommendations of high tariffs on aluminum and steel - the combination of protectionism and ever-widening trade imbalances becomes all the more problematic for a US economy set to become even more dependent on foreign capital. Far from sound, the fundamentals of a saving-short US economy look shakier than ever.

Lacking a cushion of solid support from income generation, the lack of saving also leaves the US far more beholden to fickle asset markets than might otherwise be the case. That's especially true of American consumers who have relied on appreciation of equity holdings and home values to support over-extended lifestyles. It is also the case for the US Federal Reserve, which has turned to unconventional monetary policies to support the real economy via so-called wealth effects. And, of course, foreign investors are acutely sensitive to relative returns on assets - the US versus other markets - as well as the translation of those returns into their home currencies.

Driven by the momentum of trends in employment, industrial production, consumer sentiment, and corporate earnings, the case for sound fundamentals plays like a broken record during periods of financial market volatility. But momentum and fundamentals are two very different things. Momentum can be fleeting, especially for a saving-short US economy that is consuming the seed corn of future prosperity. With dysfunctional policies pointing to a further compression of saving in the years ahead, the myth of sound US fundamentals has never rung more hollow.

Stephen S. Roach, a faculty member at Yale University and former Chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2018. www.project-syndicate.org