US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson visited the Middle East last weekend with two simple aims - to wrap Iraq into America's regional axis against Iran, and persuade Saudi Arabia to end its blockade of Qatar. He failed to accomplish either.

The dust was barely settling on the capture of Islamic State's de facto capital Raqqa, a major success for Washington and the coalition it assembled across the region and beyond. While most of the actual fighting has been done by local forces, without US support the Islamist group would still almost certainly dominate huge swathes of the region. Its dramatic early victories in 2014 seriously rattled authorities in Baghdad and Riyadh in particular - but now that it is largely on the ropes, neither government has much appetite for being dictated to by America.

Those in the Trump and Obama administration might be loathe to admit it, but over the last three years both followed a similar approach on Middle East policy. Occasionally dubbed "ISIS first," it prioritised the group's defeat above all other regional interests. It was a reasonable approach, and - while remnants of IS remain - it has proved remarkably successful.

The problem is that there is little clarity on what will now define US Mideast policy. Without a single guiding principle, there is the real risk that an already-conflicted approach could fall apart entirely.

In some respects, this is already happening. With the diminished threat from IS, Washington's always awkward alliance with the Shi'ite-dominated, Iran-allied Baghdad government and the various political entities of Iraqi Kurdistan has deteriorated with dramatic speed. A Kurdish independence referendum last month was followed quickly by an Iraqi government advance into oil-rich areas around the Kurdish city of Kirkuk. For much of the last week, Kurdish and Iraqi government forces - both US-funded and equipped, and until recently allies in the bloody battle for Mosul - have been at each other's throats.

Across the rest of the region, the historical Sunni-Shi'ite rivalry continues to grow more complex. In Syria, Iran and Russia have essentially succeeded in their attempts to salvage Bashar al-Assad's regime. Washington appears to have accepted this as the cost of stability and pushing back against Islamic State, while giving Saudi Arabia effective carte blanche to pursue its own war in Yemen against Houthi rebels allied with Tehran.

With IS weakened, the Trump White House clearly now hopes to make the confrontation with Iran its overarching regional priority. Trump's October 13 announcement that he would not recertify the nuclear deal negotiated by the previous administration was the clearest signal of that so far, followed closely by new sanctions against Iran's Revolutionary Guard, which the US labels a sponsor of terror.

On Iran, however, Washington has little realistic chance of achieving the wide, unified coalition it formed against IS. America's allies remain deeply divided on the best approach to Tehran, with European states openly reluctant to tear up the nuclear agreement also signed by Moscow and Beijing.

The Gulf states are anything but a unified coalition. The Saudi and United Arab Emirates-backed blockade of Qatar continues, putting the United States - which has major military bases in all three countries - in an awkward position, one it appears to have extremely limited ability to remedy.

The face-off between Qatar and neighbours long-infuriated by its support for groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood may now be beyond Washington's ability to resolve. If anything, however, Tillerson was even less likely to achieve his other objective for the visit, that of turning the Iraqi government against Tehran.

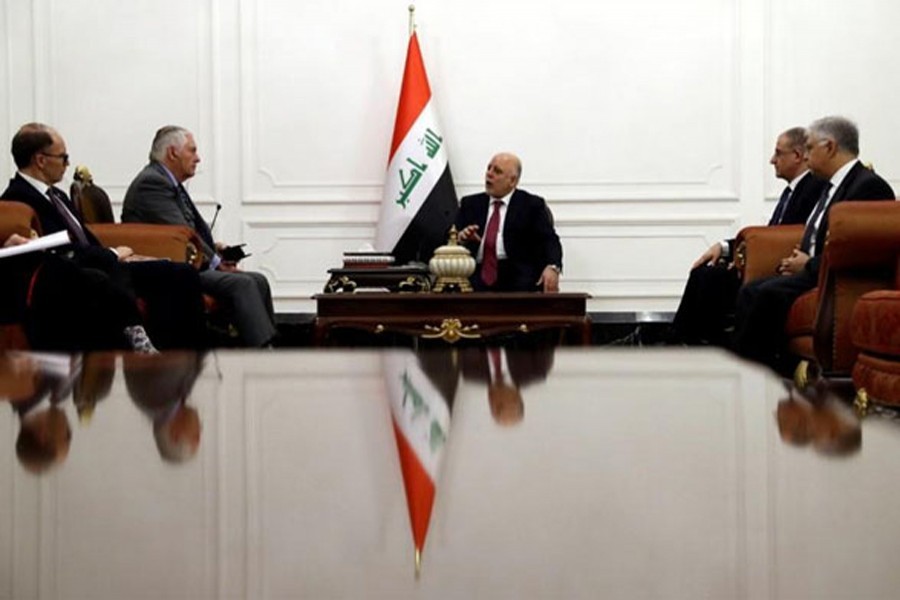

When it comes to defeating Islamic State, Baghdad has been at least as dependent on Iran-backed Shi'ite militias as on Washington or the Kurds. Tillerson's demand this weekend that those militias return to Iran will have been seen as particularly unreasonable - not least because many of their members are Shi'ite Iraqi nationals.

Tillerson's visit risks reinforcing a narrative that had been growing in strength since the Obama administration - that America has ever-less control and influence over traditional friends and enemies alike, particularly at a time when they increasingly feel they can turn to alternatives such as Vladimir Putin's Russia. Under President Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey - a reliable US ally as far back as the end of the nineteenth century - has become increasingly hostile. Egypt's military government too is increasingly keen to assert its independence, even as it continues to receive large quantities of US aid.

Relations with Israel might be marginally better under Trump than Obama but they remain much looser than in recent decades. Trump has sent mixed signals on a two-state solution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; suggested - but not acted upon - moving the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and unsettled Israelis after reports that he disclosed Israeli-provided classified information about Islamic State to Russia's foreign minister earlier this year. Israel's concerns about Iran's rising influence and an unpredictable US administration make it likely that the Jewish state will intensify its own efforts at regional diplomacy, particularly with the Gulf states.

It's a paradox that this is happening at the same time as the largely successful coalition effort against Islamic State - a coalition that depended heavily on the United States, and which perhaps no other country could have ushered into existence in quite the same way. In contrast to the unilateral US military intervention in Iraq, Washington went to great efforts to work with and through regional partners, and it has proved remarkably effective. (The irony isn't confined to the Middle East. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte is celebrating a US-assisted victory over IS in Marawi City at the same time that he intensifies his courtship of Russia and China.)

US military assistance will remain. IS is not completely gone, and will continue to lash out. It may yet seize new safe havens as it has in parts of Libya and Afghanistan. The wider battle against al Qaeda-inspired militancy will unquestionably continue, often with US military support and coordination.

After more than a decade of war and perceived failure, however, America's enthusiasm for attempting to reshape the Middle East may be running out. But even if it isn't, the willingness of those in the region to listen may also be exhausted.

The writer is Reuters global affairs columnist, writing on international affairs, globalisation, conflict and other issues. The views expressed in this article are not those of Reuters News.