President Donald Trump lost. But Trumpism did not.

It won in the parts of the country and with the voters whom Trump catered to over four years, constantly jabbing the hard edges of almost every contentious cultural issue into Red America, on the bet that fear and anger were a winning hand. It almost was.

Joe Biden defeated Trump to win the presidency, and is on pace to win up to 306 electoral votes, a total that would match what Trump exaggerated as a “landslide” four years ago. In a typical election year, such a victory would mean Biden would have carried other Democrats along with him. Instead, several promising Democratic Senate and House candidates, including incumbents, lost.

For Trump, the situation was the inverse. His popularity among his base voters helped protect incumbent Republicans but was not enough to save him. He won more votes for president than any other candidate. Except Biden. The rejection of Trump was personal.

The election did little to suggest that the country was suddenly less polarized. Trump wrung out votes from areas where he already had a core of support, in rural and small-town America. Biden did the same, only more, in urban and suburban America while also holding down Trump margins in some rural areas. The outcome didn’t change the fact that much of the country is still speaking two different political languages.

“This defied everyone’s expectations. Everyone said if Joe Biden wins, Democrats win the Senate. If Trump wins, Republicans win the Senate,” said Rahm Emanuel, the former mayor of Chicago and chief of staff to President Barack Obama. “That’s not what happened. Clearly there was an undertow.

“Life is not binary,” Emanuel said. “It’s more complicated. Florida, a state that voted for Trump, voted for the minimum wage. Illinois, a state that voted for Biden, voted down a progressive income tax. California, cobalt blue, voted against affirmative action in the place of employment.”

Emanuel said that Democrats may have erred in not offering clearer plans about how they would rebuild the economy while also gaining control over the virus and in not batting back Republican efforts to label them socialists.

“Trump played to people’s fatigue about COVID,” he said. “If we had brought the same sense of urgency to getting the economy moving as we did getting COVID under control, it might have been different.”

Instead, some Democrats were advocating for expanding the Supreme Court and ending the filibuster in the Senate, proposals that might have prompted fear about one-party control.

“It’s clear there was more voter frustration with Trump than with the ideology of the Republican Party,” said Mike Murphy, a strategist to several Republican presidential campaigns who broke with his party over Trump. “Clearly the presidential race was operating in its own world from the congressional race.”

Since Trump campaigned largely on friendly turf, he also helped Republican candidates in those areas.

“Trump lifted Republican candidates by vastly boosting turnout in areas of Republican strength,” said David Axelrod, former senior adviser Obama. “In the states and districts that favor Republicans, they ran up the score.”

Many voters offered a consistent refrain about Trump: They liked his policies but could not abide his anger-fueled personality, his constant use of Twitter as a weapon, and the way he ridiculed anyone who dared disagree with him.

Biden’s call for a return to decency, and his appeal to be a president for all Americans and not just the base of his party, was an important part of his formula.

But the closeness of the race, even with the president’s persistently low approval ratings, was also a testament to the inherent power of an incumbent seeking reelection. There’s a reason only three elected incumbents before Trump had lost in nearly a century.

When an incumbent loses, the challenger’s party often gains. In 1980, when Ronald Reagan defeated President Jimmy Carter, Republicans took 12 Senate seats from Democrats. In 1992, Bill Clinton’s victory over President George H.W. Bush also came with three Democratic Senate victories over incumbent Republicans. When Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated President Herbert Hoover in 1932, Democrats gained nearly 100 House seats and a dozen in the Senate, giving Roosevelt the muscular majorities he needed to pass sweeping New Deal legislation.

But no president in recent memory had maintained such iron-grip allegiance from his own party as Trump, with only a handful of Republicans in Congress ever willing to cross him, fearing that they were always one presidential tweet away from a primary challenge. They stuck with him during his impeachment, when only Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, voted to convict him, and Trump ostracized him. And several were sticking with him even in defeat, offering up unproven allegations of voter fraud.

Some voters liked Trump’s tough talk on trade and getting other nations to pay more for common defense. They gave him credit, right or wrong, for an economy that was buoyant before the pandemic struck. And Trump played to Americans’ fatigue from all the restrictions imposed because of the virus by saying the warnings of his own administration’s top public health officials were overblown.

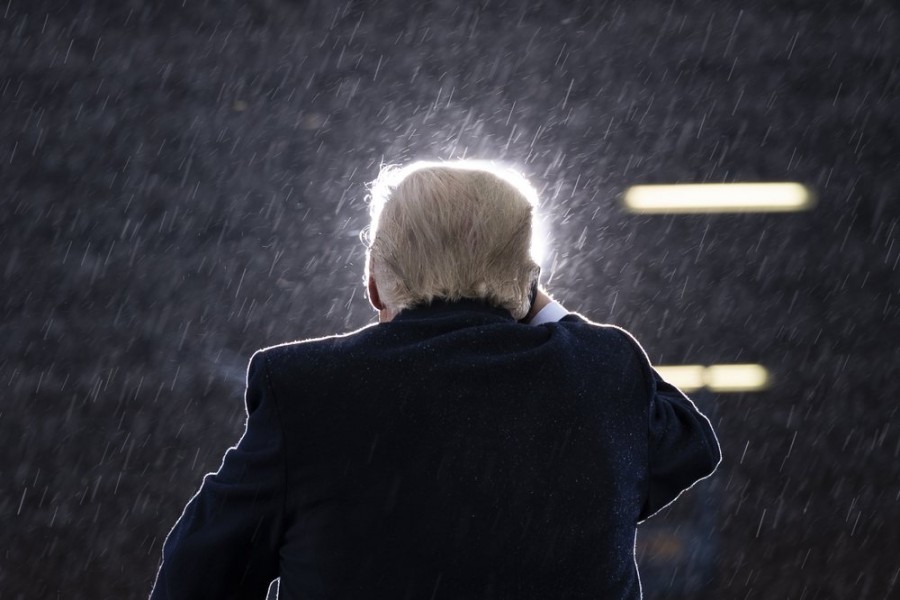

Still, there was a collective limit to how much more of Trump’s always-in-your-face presidency they were willing to take.

Not enough, though, to deliver Biden a majority in the Senate, at least not until the outcome of two runoff elections in Georgia in January.

But some Democrats also noted that they held most seats in swing states, and that Biden won in some competitive districts. “There are also many districts that Biden flipped from 2016, like my district,” said Rep. Elaine Luria of Virginia. She said her margin of victory over the same opponent more than doubled from 2018.

“The bottom line on Republicans winning in traditionally Republican-held seats was their unprecedented turnout,” Luria said. “Trump was not able to capitalize on that turnout himself, because his actions and rhetoric over the last four years made him unpalatable to the majority of Americans.”

Biden clearly was seen as both a necessary and acceptable alternative. He had no pithy slogan like “Hope and Change” when he was Obama’s running mate in 2008. Rather, he tapped into a national desire to stop the noise, to turn the page from a period so marked by rage and hate inspired from the White House itself.

The article was published on Nov 8, 2020, on apnews.com.