The gross domestic product (GDP), export and import of goods and services are very significant macroeconomic indicators and integral part of the total developmental efforts and national growth in all economies. Exports can largely meet 'foreign exchange gap' and also enhance the import capacity of a country. It is argued that foreign currencies brought through export earnings facilitate the import of capital goods, which in turn increases production potential of an economy. Apart from this, the export and import performance has tangible effect on the GDP that leads to supportive trade climate in a country, resulting in boosting up of industrialisation as well as overall economic activities. All these depend on how the state policies function to facilitate trade openness and create business-friendly environment in the country.

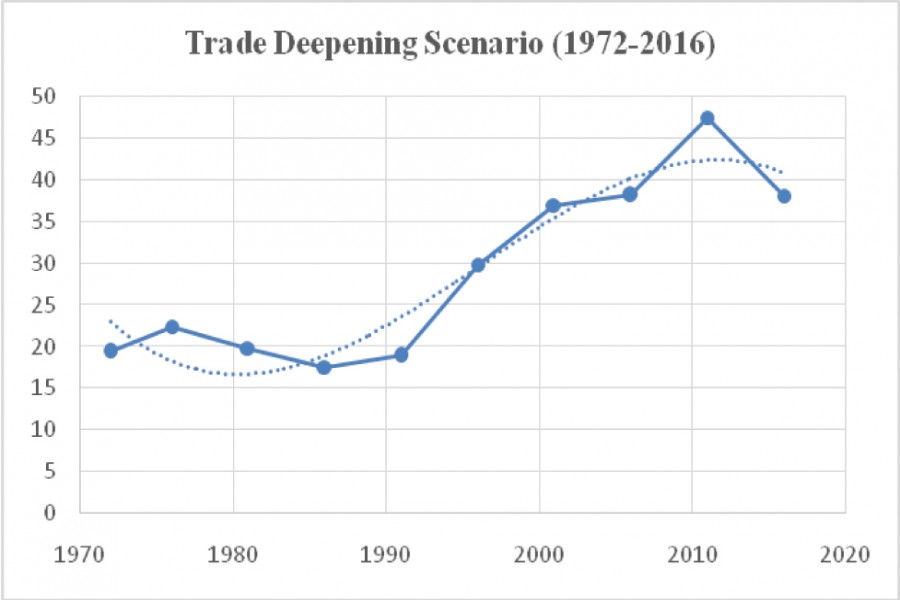

The calculation of trade deepening is based on trade shares (outcome openness measure), which translates to exports plus imports divided by GDP. In short, it is the ratio of total trade (exports cum imports) as the percentage of GDP. The increased volume of exports and imports helps a country to be more global and also aids in forging integration with other countries of the globe in terms of trade. By the same measure, Bangladesh as a developing country is positioned as one of the crucial actors in global trade that experiences critical business barriers within and outside the country. The trade deepening figure of the country started with 19.40 per cent in 1972, just one year after its independence; it has now reached 38.02 per cent, which shows the noteworthy trade performance of the country within a short span of time.

From the policy perspectives, Bangladesh was called a closed economy during the first decade of its birth, as only jute and few other commodities were available for export. At the same time, import of raw materials and intermediate goods was kept in abeyance due to industrial sluggishness in the country. But the country not only imported food-grain but also received food aid for feeding its people. The first decade witnessed an average 19.07 per cent of trade deepening in Bangladesh - a war-ravaged country with fragile trade situation. A study showed that political instability worsened the trade feasibility. On the other hand, hard work in agriculture kept jute production steady for export, which became the benchmark for trade deepening during the first decade (1971-1980) of Bangladesh.

Bangladesh went through the trade-related structural policy reforms during the 1980s and early 1990s, which had impact on the overall trade pattern and economic growth. The government of Bangladesh undertook a series of reforms in the external sectors during the period. In fact, the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) prescribed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had an impact on the overall macro economy of the country. The SAP was designed to eliminate aberrations and economic inefficiencies by focusing on some macroeconomic variables like balance of payments, interest rates, etc. In addition to some positive changes, SAP enabled the option of investments without verification of projects or sources of fund. So, the percentage of black money in GDP marked a phenomenal increase. It made the jute and stock market more volatile. The government had to depend on more foreign grants and loans than before, and occasionally faced shortage of fund for welfare programs. Import was out of control, and the country lacked self-sufficiency at that juncture. In fact, the instability of politics and the adoption of SAP policy led to the squeezing of trade deepening and resulted in negative growth of trade at an average rate of 0.021 per cent during the decade of 1982-1991.

Spurred by significant trade liberalisation policies during the decade of 1990s, Bangladesh's merchandise foreign trade nearly doubled and shot up to 30 per cent of GDP during the decade. Increased openness to international trade brought about considerable economic gains; eventually growth of exports became strong enough to cover imports and keep the trade deficit at a sustainable level. With laudable progress in eradicating a sizable portion of import restrictions and in reducing the average rate and dispersion of import tariffs, Bangladesh then reformed its economic policies. A report claimed that this economic restructuring made a significant departure from a highly restrictive system based on import substitution to a more dynamic, export-oriented one in the backdrop of a competitive global market by focusing on ready-made garments, knitwear, frozen food, and leather products. As a result, the decade (1992-2001) witnessed a huge upturn in trade openness, reaching an average 5.56 per cent that can be considered as the steadiest rise in trade performance in the history of Bangladesh.

The fourth decade (2002-2011) of Bangladesh was closely associated with political cliques and confrontations. Bangladesh failed to sustain its trade openness trend during the decade and the downturn in figure led to an average figure of 4.15 per cent. The policy makers barely strove to raise, explore and expand the volumes and destinations of exports. However, since 2008, a massive shift in the governmental mission and vision relating to economic policies from customary to development-oriented ones boosted trade performance by seeking new ways and destinations for exports and eliminating import barriers.

Bangladesh Economic Review 2011 revealed that the government declared the first stimulus packages in FY 2008-09 and the second in FY 2009-10 especially for the export sector to curb the negative impact of global economic recession and foster the growth of exports. This package helped the Export Development Fund (EDF) to swell from US$300 million to US$ 400 million in order to assist the export sector in the country. Besides, attempts were made to make the import policy compatible with changes in the world market and World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules. A source claimed that the export growth rate during the period might have been lower than that of 4.15 per cent if the business communities were not proactive and the government had not taken timely policy initiatives. These led to an almost stable trade performance despite colossal political upheavals faced by the country.

During the period 2012-2016, trade deepening touched the record figure of 43.75 per cent on an average. Notably in 2012, Bangladesh reached the zenith of trade openness at 48.11 per cent, which exceeded all trade deepening figures the country had recorded since its birth. But the compound trade deepening figure during these years marked a negative growth of 5.68 per cent, as Bangladesh's export basket increasingly looks like a 'tadpole' - an early phase of a frog's life cycle with a big upper part of the body (i.e. large volume of export originating from limited number of products), which is linked to a narrow middle part (i.e. moderate volume of export of few products) and long tail in the lower part (i.e. small volume of export of large number of products). Overall, Bangladesh lags far behind in terms of developing a diversified export base with regard to both products and markets.

In 2016, a BMI research claimed that Bangladesh's trade balance, or the difference between exports and imports, was likely to worsen slightly during fiscal 2015-16 as imports might surge on the back of a strong taka. A 2016 report said that the reason for the slow import growth was the lack of investment appetite. Not only the industry-related items, the import of other goods like food and petroleum declined. All these factors were crucially responsible for the negative trade deepening during the past five years (2012-2016).

In this backdrop, Bangladesh has made, like other developing countries, significant progress as an exporter of manufactured goods, but it is yet to diversify its export-base due to a limited level of comparative advantage. Policy makers should pay heed to this. Trade gaps between Bangladesh and India as well as non-tariff barriers (NTBs) have remained as bones of contention between the two countries. As import restrictions are less than that of previous decades, it may help our import promotion. In that case, priority should be given to import of raw materials and intermediate goods for expanding value-added industries, which may have significant impact on industrialisation in the country.

For continuous deepening of trade, the country should adopt more export-oriented policies as expansion of exports may generate more foreign exchange for payment of import bills and enhance capital accumulation. Bangladesh needs to use the preferential market access facilities to a greater extent. It should strongly raise the issue of NTBs at bilateral discussions and government-to-government (G2G) negotiations with emerging countries, especially with neighbouring India, and also improve its domestic institutional base for monitoring the technical standards. All these policies and programmes can pave the way for upgrading the existing trade deepening in the country.

As Bangladesh hopes to become a middle income country in 2021 and a developed nation by 2041, sound trade policies for the optimal growth of trade deepening do matter. The government policies should be private sector-friendly for encouraging the private entrepreneurs to invest in the export-based production sectors. Policy makers of the country should groom a knowledge-based group who may be deployed for tackling all types of trade barriers faced by the country and move forward to obtain or maintain Generalised System of Preferences (GSP).

Monirul Islam is an Assistant Professor at Bangladesh Institute of Governance and Management (BIGM). [email protected]