The International Monetary Fund (IMF) published its World Economic Outlook for 2020 and 2021 last Tuesday (April 14). Amid the Covid-19 pandemic and the world currently looking like some kind of a dystopian movie with empty streets, hundreds of millions of people in lockdown, production facilities shut down, shops shuttered, planes grounded in abandoned airports, grim prospects for the global economy have grown even darker as outlined in the IMF forecast. The IMF predicts that the global economy will be in worse shape than it was in during the Great Depression (1929-33) and the loss of output will "dwarf'' that suffered in the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-08.

The new forecast assumes that the pandemic peaking in the second quarter of this year in the most countries in the world and to be followed by a partial recovery next year from the "Great Lockdown'' of 2020. But the economists at the IMF did not sound entirely convinced. IMF Chief Economist Gita Gopinath said "Much worse growth outcomes are possible, may be even likely''. In the worst case scenario, the global economy would shrink by around 11 per cent rather than 3.0 per cent. Also, for the first time since the Great Depression both advanced and emerging market and developing economies are in recession.

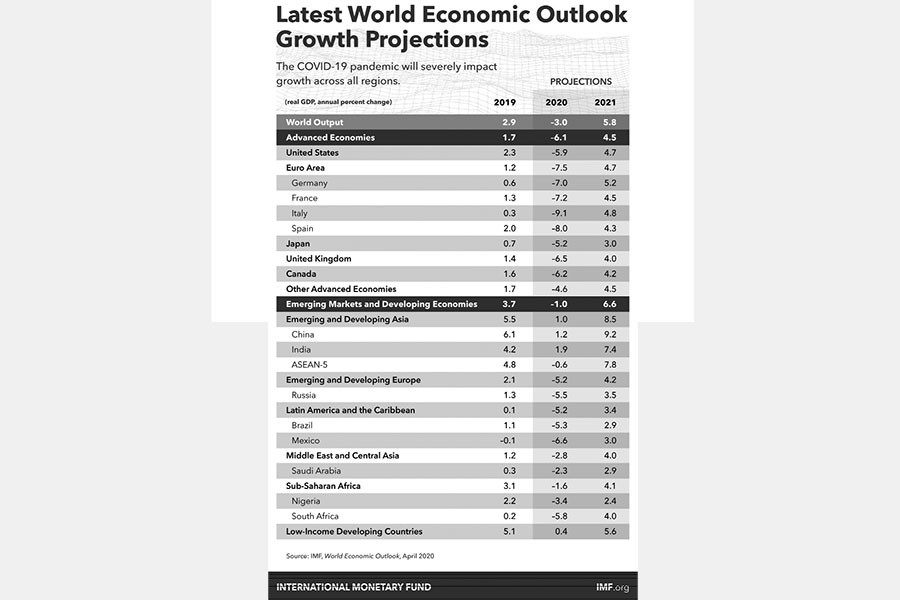

The new forecast sees the global economy contracting at a 3.0 per cent annual rate this year, a 6.3 per cent fall from the forecast issued in January this year. However, the global economy will rebound by a 5.8 per cent in 2021. But even if that takes place, the recovery will only be "partial'' with the level of activity that was projected for 2021 before the virus struck.

It further said all together the cumulative loss to global economy over 2020 and 2021 could be US$9.0 trillion in terms of output (GDP). This amount is equivalent to the combined economies of Japan and Germany, the world's third and fourth largest economies respectively. There are even more pessimistic scenarios. If the pandemic is more protracted and continues into 2021, it could reduce the level of global GDP (gross domestic product) by 8.0 per cent compared with the baseline scenario.

The IMF further predicted the contraction of growth by 6.1 per cent in advanced economies with the US economy contracting by 5.9 per cent, Japan 5.2 per cent and Germany 7.0 per cent. Developing economies, except China, are expected to experience negative growth rates between 1.0 and 2.0 per cent. Income per capita will fall in more than 170 countries.

The IMF also issued a warning about the state of global financial system and said "further intensification of the crisis would affect global financial stability''. However, the massive injection of trillions of dollars by central banks and their willingness to do more if necessary has stabilised markets in the major financial centres around the world. US markets are surging and continuing the mostly upward trend over the last week despite record unemployment claims and poor bank performance.

Former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen in a television interview warned that job losses (in the US) could continue to worsen. She predicted the unemployment rate will reach levels not seen since the Great Depression. But she was hopeful that once the health crisis gets under control, the economy will recover much more speedily than it did from any past downturn.

In Europe the health crisis combined with already struggling European economies have also created a political crisis. In the European Union (EU), where the initial response of member states has been to close borders and for each to look after its own citizens has put enormous stress on countries worst hit by the pandemic like Italy and Spain. These countries failed to elicit any meaningful help from other EU countries which prompted the prime minister of Italy Guiseppe Conte to remark "If Europe does not rise to this unprecedented challenge, the whole European structure loses its raison d'etre to the people. We are at a critical point in European history.''

Meanwhile, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) indicated that global trade would shrink between 13 and 32 per cent in 2020 relative to the previous year due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Nearly all regions will suffer double-digit decline in trade volumes in 2020. Estimates of the recovery in 2021 are equally uncertain. With outcomes depending largely on the duration of the outbreak and the effectiveness of the policy responses.

The International Labour Office (ILO) said that currently 81 per cent of the global workforce of 3.3 billion was affected by the full or partial workplace closures. The ILO further added that globally there were 136 million workers in human health and social work activities, including nurses, doctors and other health workers, workers in residential care facilities and social workers, as well as support workers, such as laundry and cleaning staff, who faced serious risk of contracting Covid-19. Also, there are two billion people working informally in less developed economies and tens of millions of them are now directly affected by the pandemic.

Angel Gurria, secretary general of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), on March 23 gave even a much more dire warning by saying advanced economies should prepare to suffer. He further added if they did everything right the suffering would last a year; if not, they'd never recover. He also dismissed any "V'' shaped recovery, and predicted at best a "U'' shaped recovery with a long trench in the bottom before it got to the recovery period. Only by taking right decision a "L" type recovery can be avoided. But some academic economists do not entirely rule out an "I'' shape economic trajectory - a forever freefall.

Despite such unprecedented economic and social crisis, such pessimistic outcome envisaged by Mr. Gurria and some academic economists are likely to be wrong. The current economic downturn is the outcome of a health crisis; there are not any serious or unmanageable underlying problems with most advanced economies. Also, now there are multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank who can provide safety nets to mitigate any global or regional economic crisis. Such multilateral institutions were absent during the Great Depression.

The IMF also said that the economic fallout from the pandemic can play out in ways that can be hard to predict. Many smaller economies face multilayered crises comprising of a health shock, domestic economic disruptions, the collapse in commodity prices, plummeting external demand and capital flow reversal. Many countries also face very large debt repayment. But also the shape and severity of the downturn depend not only on government policy but also on how businesses steer through adversity and refocus on growth.

There is significant uncertainty about the impact on people's lives and livelihood in developing countries. These countries have weak health systems and these are likely to be overwhelmed delaying the process of overcoming the pandemic. And that will make economic recovery to take longer time period. These countries also face additional challenges like the reversal of capital flows and currency pressures and weakening overseas remittances, high debt levels and very limited fiscal space.

These countries are projected to have negative growth rates between 1.0 per cent and 2.2 per cent in 2020. They are expected to achieve partial recovery in 2021. Overall, Covid-19 now is not only a health crisis in the short run for developing countries but also likely to trigger serious social and economic crises over the months and years to come.

BANGLADESH SCENARIO: Global economic ramifications of the Covid-19 will adversely impact on the previous growth trajectory of Bangladesh for this year. As all major advanced economies are already in recession heading towards a depression, this will adversely affect developing economies like Bangladesh through exogenous trade shocks and disruptions in supply chains. Large retail outlets have already closed their stores, will significantly affect factories and workers locked into supply chains with implications for countries like Bangladesh. In the post-Covid-19 period, the restructured shorter supply chains likely to result in permanent losses of business for many firms and their employees in Bangladesh.

The Covid-19 crisis has caused increased economic vulnerability as reflected in rapid slowdown in projected growth away from the trend. Growth rate for Bangladesh, as projected by IMF, now stands at 2.0 per cent for 2020 against 7.9 per cent in 2019. However, the economy is expected to bounce back to its trend growth rate trajectory in 2021. Bangladesh GDP growth is projected to be at 9.5 per cent in 2021. But that growth rate trajectory is entirely dependent on how soon Bangladesh is able to bring the pandemic under control.

A sample survey conducted by BRAC indicates that millions of low-income people in the country are experiencing serious economic hardship due to social distancing and lockdowns. The report further added that average monthly household income of respondent households dropped from US$172 before the viral outbreak to US$42 after the outbreak. More disturbing finding is that 14 per cent of country's poor have no food.

Such sudden turn of events caused by the pandemic calls for the government to act decisively with the provision of significant financial stimuli and further extension of social safety nets. Also, to mitigate the increasing unemployment, consideration should be given to job retention support to business enterprises as well as tax credits could be extended to business enterprises that do not lay off workers, especially during the recovery period. But for unemployed worker in the informal sector direct cash handout or similar kind of assistance is the only means available to the government to enable these people to tide over the pandemic crisis. In this very difficult and challenging time in the nation's history, the government is to make citizens feel secure and less fearful by providing good publicly-funded health care services and income support for the poor, elderly, sick and the unemployed.

Muhammad Mahmood is an independent economic and political analyst.