JOHANNESBURG - As the US Federal Reserve embarks on the "great unwinding" of the stimulus programme it began nearly a decade ago, emerging economies are growing anxious that a stronger dollar will adversely affect their ability to service dollar-denominated debt. This is a particular concern for Africa, where, since the Seychelles issued its debut Eurobond in 2006, the total value of outstanding Eurobonds has grown to nearly $35 billion.

But if the Fed's ongoing withdrawal of stimulus has frayed African nerves, it has also spurred recognition that there are smarter ways to finance development than borrowing in dollars. Of the available options, one specific asset class stands out: infrastructure.

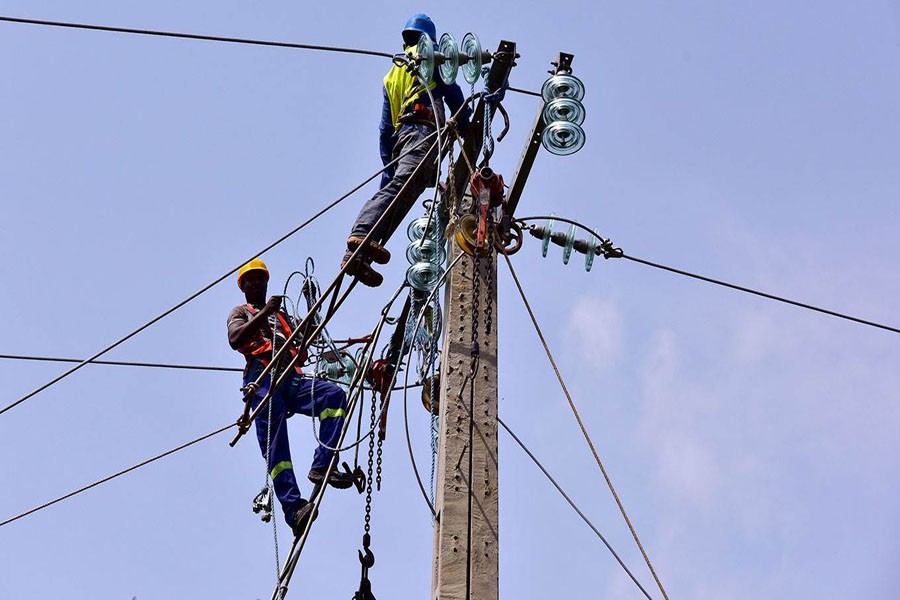

Africa, which by 2050 will be home to an estimated 2.6 billion people, is in dire need of funds to build and maintain roads, ports, power grids, and so on. According to the World Bank, Africa must spend a staggering $93 billion annually to upgrade its current infrastructure; the vast majority of these funds - some 87 per cent - are needed for improvements to basic services like energy, water, sanitation, and transportation.

Yet, if the recent past is any guide, the capital needed will be difficult to secure. Between 2004 and 2013, African states closed just 158 financing deals for infrastructure or industrial projects, valued at $59 billion - just 5.0 per cent of the total needed. Given this track record, how will Africa fund even a fraction of the World Bank's projected requirements?

The obvious source is institutional and foreign investment. But, to date, many factors, including poor profit projections and political uncertainty, have limited such financing for infrastructure projects on the continent. Investment in African infrastructure is perceived as simply being too risky.

Fortunately, with work, this perception can be overcome, as some investors - such as the African Development Bank, the Development Bank of Southern Africa, and the Trade & Development Bank - have already demonstrated. Companies from the private sector are also profitably financing projects on the continent. For example, Black Rhino, a fund set up by Blackstone, one of the world's largest multinational private equity firms, focuses on the development and acquisition of energy projects, such as fuel storage, pipelines, and transmission networks.

But these are the exceptions, not the rule. Fully funding Africa's infrastructure shortfall will require attracting many more investors - and swiftly.

To succeed, Africa must develop a more coherent and coordinated approach to courting capital, while at the same time working to mitigate investors' risk exposure. Public-private sector collaborations are one possibility. For example, in the energy sector, independent power producers are working with governments to provide electricity to 620 million Africans living off the grid. Privately funded but government regulated, these producers operate through power purchase agreements, whereby public utilities and regulators agree to purchase electricity at a predetermined price. There are approximately 130 such producers in Sub-Saharan Africa, valued at more than $8.0 billion. In South Africa alone, 47 projects are underway, accounting for 7,000 megawatts of additional power production.

Similar private-public partnerships are emerging in other sectors, too, such as transportation. Among the most promising are toll roads built with private money, a model that began in South Africa. Not only are these projects, which are slowly appearing elsewhere on the continent, more profitable than most financial market investments; they are also literally paving the way for future growth.

Clearly, Africa needs more of these ventures to overcome its infrastructure challenges. That is why I, along with other African business leaders and policymakers, have called on Africa's institutional investors to commit 5.0 per cent of their funds to local infrastructure. We believe that with the right incentives, infrastructure can be an innovative and attractive asset class for those with long-term liabilities. One sector that could lead the way on this commitment is the continent's pension funds, which, together, possess a balance sheet of about $3.0 trillion.

The 5.0 per cent Agenda campaign, launched in New York in September, 2017, underscores the belief that only a collaborative public-private approach can redress Africa's infrastructure shortfall. For years, a lack of bankable projects deterred international financing. But in 2012, the African Union adopted the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa, which kick-started more than 400 energy, transportation, water, and communications projects. It was a solid start - one that the 5.0 per cent Agenda seeks to build upon.

But some key reforms will be needed. A high priority of the 5.0 per cent Agenda is to assist in updating the national and regional regulatory frameworks that guide institutional investment in Africa. Similarly, new financial products must be developed to give asset owners the ability to allocate capital directly to infrastructure projects.

Unlocking new pools of capital will help create jobs, encourage regional integration, and ensure that Africa has the facilities to accommodate the needs of future generations. But all of this depends on persuading investors to put their money into African projects. As business leaders and policymakers, we must ensure that the conditions for profitability and social impact are not mutually exclusive. When development goals and profits align, everyone wins.

Ibrahim Assane Mayaki, a former Prime Minister of Niger, is CEO of the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) Planning and Coordinating Agency.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2017.

www.project-syndicate.org