When this writer turned to serious Bangla literature, especially fictions, he kept himself confined to West Begngal authors. For reasons unknown to even himself, he had still nurtured an aversion for Dhaka-based novelists and short story writers. He was in the last year of his school then. When his reading-circle members were found kept glued to Syed Shamsul Haque's 'Khelaram Khele Ja' or the Masud Rana thriller series, their liking couldn't also be weaned off from the literary giants like Tarashankar, Manik Bandyopadhyay, Bibhutibhushan and the other stalwarts of Bangla fictions. Their lists also included short stories by Narayan Gangopaddhay, Tarashankar, Manik, Jyotirindra Nandi, Bimal Kar et al.

Against this backdrop, the book lovers laid their hands on a few novels and story collections published from Dhaka. Almost all of them became awe-struck as they delved into the novels and the short stories. The authors included Syed Shamsul Haque, who had already been credited with a few extraordinary prose works --- apart from, of course, 'Khelaram'. As his contemporary or near-contemporary authors, Haque found Alauddin Al Azad, Shaukat Ali, Borhan Uddin Khan Jahangir et al. All of them are considered the writers belonging to the 1950s.

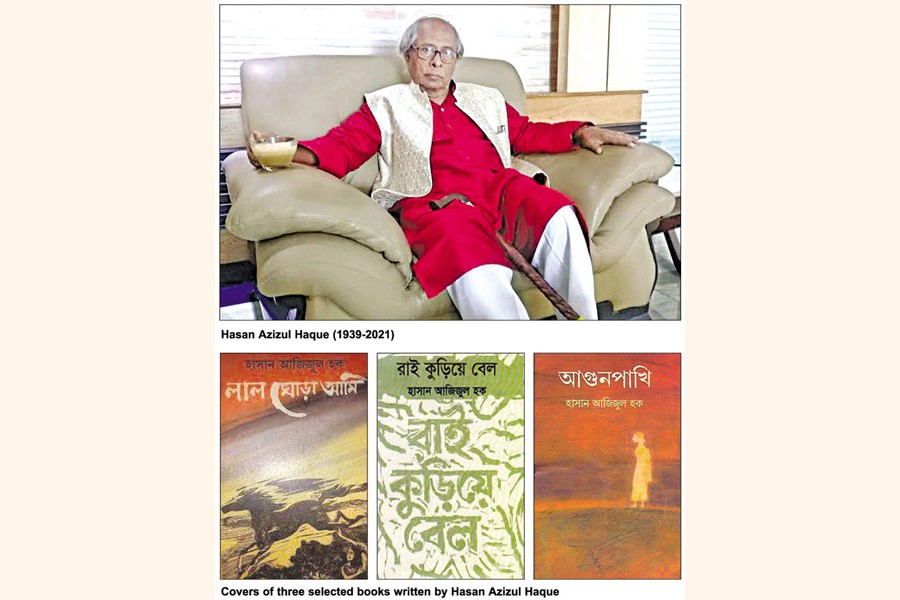

Surprisingly, our initiation into the East Bengal novels started with the stories of Hasan Azizul Haque (b1939), who passed away last November 15. When we became drawn to this relatively less known writer, he had published just two collections of stories. They were 'Somudrer Swapna Shiter Oronyo', (1964) `Atmoja O Ekti Korobi Gachh' (1967). His other books included short story collections, 'Jibon Ghoshey Agun' (1973), 'Namhin Gotrohin' (1975), 'Patale Haspataley' (1981), 'Amra Opekkha Korchi' (1988), 'Rarho Bonger Golpo' (1991), 'Ma Meyer Sangsar' (1997), 'Bidhobader Kotha O Onyanyo Golpo' (2007). Hasan's novels include 'Agunpakhi' (2006), 'Sabitri Upakhyan' (2013), 'Shamuk' (2015). We the new readers of Hasan became ardent admirers of the writer after reading his very first collection of stories. We read them three to four years after their publication. By the time Hasan Azizul Haque published his second collection in 1967, we had reached the doorstep of our Secondary School Certificate exams. All of us, especially we three avid readers, had proved ourselves to be prematurely mature (ichre paka) readers. In our judgement, Hasan Azizul Haque was emerging as a major writer in the eastern part of Bengal. It didn't take long for us to realise that this writer's work belonged to the genre of a unique realism, soaked with quintessentially romantic and lyrical features --- both in the treatment of his subject and his diction. During the period of Hasan's post-debut phase of evolution, he developed a prose-style not seen before in Bangla stories or novels. Many readers may become incredulous or feel perplexed if some avant garde critics distinguish the writer as one subconsciously submerged in poetry. The writer himself doesn't realise the fact that in almost all of his stories, especially the earlier ones, he leaned greatly towards poetry. From the portrayal of characters to that of their locales, it was the poeticism that effused from his stories. Thanks to this rare artistic virtue which takes a creative and realistic prose writer to the realm of poetry, Haque remains an author apart from his contemporaries. They are both his senior and junior by age. The Dhaka-based prose writing activities in the 1960s were dominated by a number of widely admired and popular authors. The time was distinguished by the common trend of plain store-telling. Even the decade's stellar authors didn't show any keen interest in experimenting with their characters and prose.

Stunningly, a seclusion-loving writer took the much-awaited attempt. The author was Shahed Ali. His short story 'Jibrailer Daana' proved in time the key to a world rich with the gifts of both dream and the mundane. Some also feel tempted to discover in Shahed Ali a perfect symbolist. Many critics went further in the following in days. They attempted to place Ali in the class of a 'magic realist', with a dressing of spiritual longing. Likewise, Hasan Azizul Haque achieved a distinctive style befitting his realism, soaked in the apparently unreal, in his very early stories.

In that conventional literary landscape that began expanding fast in the 1950s, the well-known writers did not bother to step outside the time's middle-class environs. Except 'Roktogolap', Syed Shamsul Haque remained peacefully ensconced in the fast-consolidating ambience of Dhaka's urban reality. But among Syed Haque's contemporaries, like Alauddin Al Azad or Saiyeed Atiqullah, it was only him who showed the penchant for delving into the psychological abyss of his characters, say, Babar Ali. Yet he didn't go further, apparently in fear of attacks from the conservatism which had gripped society. After 'Khelaram', Syed Haque shunned the path of peeping into his own and others' subconscious. Later, the most celebrated author of Bangladesh, Syed Haque turned to the socio-political issues and subtle psychological turbulence of the urban middle and upper middle-classes.

Surprisingly, even after the great outcry over and the sales success of Samaresh Basu's 'Bibor' (1965) and 'Projapoti' (1967), featured by the protagonists' parenthetical soliloquies, Syed Haque didn't turn to that path. Maybe, something grand and of epic proportions started beckoning him in the decade as early as the late-1960s.

Despite the fact that many readers and critics dubbed him as being in the domain of Manik Bandyopadhyay or partly Premendra Mitra, Hasan Azizul Haque created a distinctive world unique to him only. As the discerning readers find themselves amid a fictional ambience not experienced before in Bangla language, Hasan emerged as a major short story writer in the sub-continent's literary landscape. On the other hand, in spite of his being a writer having the subconscious leaning towards the left, the Bengalee author doesn't portray the harsh realities like done by Manto, Abbas or Premchand.

In his stories, Hasan Azizul Haque is never found oblivious to his Bengal roots. Thanks to this fact, the readers do not fail to discover a true portrayal of this land in his stories. In his hand the land's beauty continues to be enhanced with the changes in the looks of landscapes. Admiring readers find this beauty being dominated by both suave and harsh natures. With such ever-changing seasonal charms offered by the humid and the mostly flood-dominant country, the writer hardly fails to detect the backbreaking toil the socially marginalised put in to eke out a living. Some of them manage to stay afloat somehow. Others find little space in their struggle to have the luxury of indulging in dreams. Still the unremitting, tooth-and-nail fight of Hasan's characters to survive in this often adverse world, finally, stops at a certain point. Here they are given the choice of an interregnum to reflect on this earthly existence.

The result is amazing; at times it sees the men and women in his writings being pushed into endless courses of bewilderment. On other occasions, some of them are seen at the entrance of the celebrations of life. Being unable to muster enough courage, they remain hesitant at the gateway to the world which has the rewards for them in store. They are too weak to raise their voice.

Both defeated and triumphant people keep appearing in Hasan Azizul Haque's stories. It is one of the dominant features of this major creator of Bangla short stories. In the newly shaping Bangla literary scenario, Hasan Azizul Haque found an area already prepared for him. He couldn't resist the signs of beckoning to the world of fresh short stories. He presented the Dhaka-based literature dozens of marvellous stories not experienced before. Though Hasan may have turned to Bimal Kar, Jyotinindra Nandi or a few pieces written by Manik, he was quite fortunate. Hasan didn't have to wait much to ensure a lasting place in Bangla literature. The struggle for bare survival coupled with the day-to-day realities of the rising middle class had kept shaping his short stories.