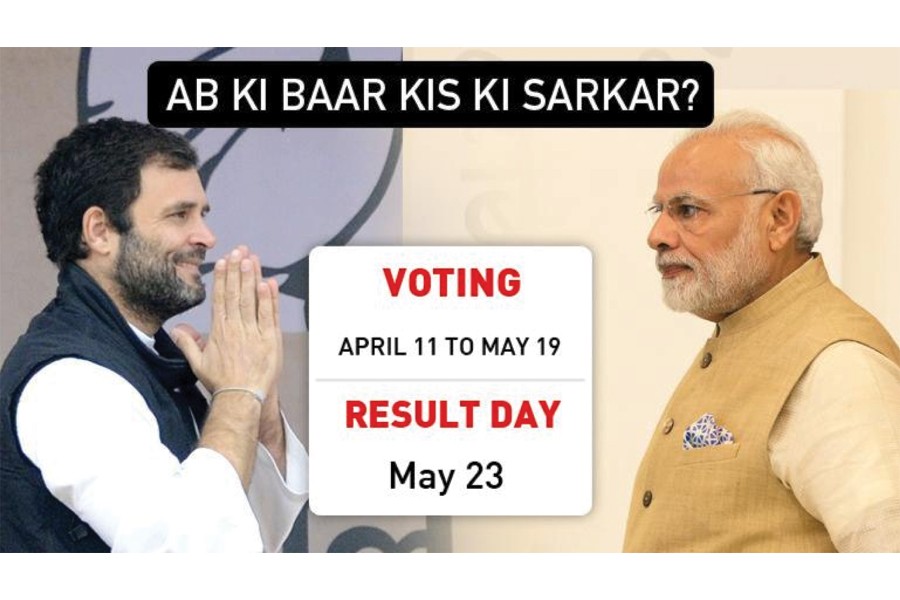

The Indian Election Commission has announced on March 10 that India's next general election will take place in seven phases between April 11 and May 19; votes will be counted on May 23. Lok Shaba (the lower house) has 543 elected seats and any party or coalition will need a minimum of 272 MPs to form a government.

One needs to understand the enormity of this colossal matrix. This time, more than 900 million people above the age of 18 are eligible to cast their ballots at nearly a million polling stations. The number of voters will be bigger than the population of Europe and Australia combined. Indians being enthusiastic voters by nature, the turnout in the last general election in 2014 was more than 66 per cent, up from 45 per cent in 1951 (when the first election was held). More than 8,250 candidates representing 464 parties contested the 2014 elections, nearly a seven-fold increase from the first election.

The Lok Shaba voting will be held this year on April 11, April 18, April 23, April 29, 6 May 06, May 12 and May 19. Some states will hold polls in several phases. It may be recalled that India's historic first election in 1951-52 took three months to complete. This improved somewhat between 1962 and 1989, when elections were completed in four to 10 days. The four-day elections in 1980 were the country's shortest ever. This time it will take 39 days.

Elections in India become long-drawn-out affairs because of the need to create security in polling stations through the deployment of not only local police but also federal forces. India's Centre for Media Studies estimates that in the last election held in 2014, parties and candidates throughout the country spent nearly US$ 5.0 billion. Analysts think that this time the total figures of overall expenditure might reach nearly double of that amount. It would be interesting to note here that comparably the free-spending presidential and congressional elections in the USA in 2016 saw an expenditure that reached almost US$ 6.5 billion.

An interesting aspect that has been drawing the attention of observers is the gradual increase in the number of women taking interest and vote in Indian parliamentary elections. Some have observed that that this time more women than men might vote in the elections. In 2014 the vote gender gap had already shrunk and the turnout of women was 65.3 per cent as against 67.1 per cent for men. Several local elections in 2018 have demonstrated that the turnout of women was higher than men in two-thirds of Indian States. This probably happened because several political parties have been focusing on women as a constituency and offering them, particularly in rural India, different kinds of gifts - from education loans to free cooking gas cylinders and even cycles for girls.

BJP VERSUS CONGRESS: In 2014, Prime Minister Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) received almost a third of the popular vote and won 282 of the 428 seats it contested. This was the first time since 1984 that any Indian political party had won an absolute majority by itself in a general election. This success was attributed to Mr Modi having the ability to promote himself as a decisive, hardworking leader who believed in ushering in, after 2014, a corruption-free "better times". Analysts believe that the 2019 election will not only be a referendum on how Modi has performed in promoting India's socio-economic agenda but also on the manner in which his government has been able to ensure India's security through their armed forces and law enforcement authorities.

Comparably there is a different sort of focus on the 133-year-old Congress party. In 2014, the party suffered its worst-ever defeat in a general election. It won a mere 44 seats - compared to 206 seats in 2009 - and picked up less than 20 per cent of the popular vote. This poor showing continued for this prestigious party through their string of losses in State elections over the next four years. It came to a point where in the middle of 2018, the Congress and its allies ran only three State governments, while BJP and its partners ran as many as 20. Consequently, many observers made critical references and observed that unless things turned for the better its leader Rahul Gandhi, fourth generation scion of the famous Nehru-Gandhi family, had no chances in the future.

Such criticism however became slightly low-key in December, 2018 when the Congress staged a partial revival by winning three key northern States from the BJP. Many attributed this recovery to anti-incumbency factor as two of the three States had been ruled by the BJP for years. Others suggested that this swing had taken place because of the more active involvement of the Congress leadership at the grassroots level. The recent involvement of Rahul Gandhi's charismatic sister Priyanka in active Congress Party politics appears to have added an evolving dynamics to the electoral exercise.

This revival of the Congress Party has enabled it to rejuvenate a fractured opposition. This has led many political scientists to believe that 2019 will see a greater contested scenario.

ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL MATRIX: Many socio-economists and academics have been focusing on the economic and financial matrix operating currently in India, Asia's third largest economy, and how it might cast its own shadow on the elections.

There have been references in this regard to a coin having two sides. Different political parties are trying to exploit them to their respective advantages.

Some critics are saying that under Modi the economy has lost the requisite momentum. They are pointing out that in the past two years farm incomes have stagnated because of a crop glut and declining commodity prices. This has led to angry farmers being saddled with debts and creation of bad loans in some of India's state-owned banks.

They are also drawing attention to the contentious 2016 currency ban - locally called 'demonetisation' - and the complex and badly executed new uniform goods and services tax that has affected small and medium entrepreneurs. This in turn has also led to reduction in export in some tertiary sectors.

It is being alleged that this dynamics has reduced growth and has had an adverse effect on generating employment in India's huge informal economy both in the rural and urban areas. Over the last two years this has emerged as a giant challenge. Economists have pointed out that this is drawing special focus as more than half of Indians are aged 25 or under, and some 12 million enter the workforce in that country each year.

On the other hand, BJP supporters highlight certain positive facts within the financial sector. They have pointed that inflation is in check, increased government spending in infrastructure and public works has created dynamism within the economy and that despite some constraints growth is expected to be at least 6.8 per cent this fiscal year. Mr Modi's government has also announced direct cash transfers to farmers and waivers of farm loans. It has also promised job quotas for the less well-to-do among the upper castes and other religions.

Pro-Congress analysts however have been quick to point out that India's GDP (gross domestic product) needs to grow at a rate faster than 7.0 per cent for the country to continue to pull millions out of poverty.

MUSCULAR NATIONALISM AND POLITICAL HINDUISM: Some analysts have also been drawing attention to another aspect that might affect the thinking of voters. They have been referring to that Party's recent approach in electioneering through muscular nationalism and political Hinduism. They believe that this might create greater divisions among the different communities living in different parts of India. Radical nationalist rhetoric has already emboldened radical rightwing groups towards aggressive enforcement of anti-slaughter laws. Consequently, the cow has become a polarising animal. People critical of radical Hinduism are also being labelled as anti-nationals and dissent is being frowned upon. This is not being liked by the left-secular and the liberal groups.

This scenario has acquired a special status after the recent tit-for-tat aerial bombings by India and Pakistan at the end of February following a deadly suicide attack in Indian-administered Kashmir. This has triggered more nationalistic scenarios and Modi has made it clear that he and BJP consider national security a key plank of his campaign.

The Opposition led by the Congress Party, on the other hand, does not appear to have been able to come up with a persuasive counter-narrative. This is bound to affect millions of swing votes going Modi's way.

The last important thing that will be followed carefully will be the evolving political dynamics in the socially divided northern State of Uttar Pradesh, home to more than 16 per cent of India's population. Eighty Members of Parliament are elected from here. In the 2014 election, the BJP won 71 of the state's 80 seats. Mr Modi's charisma and his ability to stitch together a rainbow coalition of castes contributed to this success. This time, some think that the efforts of Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) might stop such a rout. Some analysts are stating that one should not be surprised if this leads to BJP losing their majority in this State. If that happens, it will affect BJP having a direct majority in the Parliament.

The coming elections will prove which side of the coin the people have agreed with pertaining to all these different dimensions.

Muhammad Zamir, a former Ambassador, is an analyst specialised in foreign affairs, right to information and good governance.