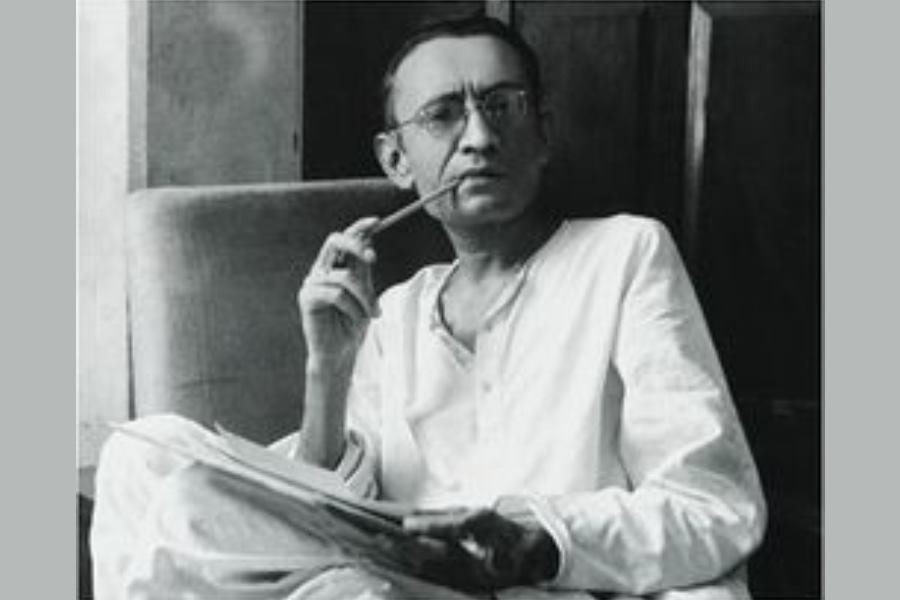

Saadat Hasan Manto, one of the unique storytellers in the history of literature, was devastated by the horrors of the partition of the British India. The aesthetic commentary on violence expressed in his writings slapped the face of our conscience cruelly. The partition in 1947 has a long-lasting impact on Bangladesh and through shared emotions, some Bangladeshi readers feel engaged with the writings of Manto even with the translated versions.

Though many criticise him for obscenity in literature, addiction to alcohol, chaotic lifestyle, non-involvement in the party politics, Manto is the artist who exhibited the same colour of dismay grown in the minds of the two legal states on both sides of the Radcliffe Line.

The life of a storyteller

Manto’s ancestors were Kashmiri. He was born in a place called Samrala on the way to Chandigarh in 1912. His father Khwaja Ghulam Hasan was a judge under the Punjab government. He had two wives, but could not provide equal status to both of them. This fact always tormented the mind of the son.

Not being able to concentrate on institutional studies, Manto failed the matriculation examination three times in Urdu and passed it on the fourth attempt, as well as failing the First Arts examination. He was also expelled from Aligarh University for tuberculosis. Although formal schooling did not give him much, he learned a lot from schools around the world.

In the 1930s, Marxist philosophy was introduced to the anti-British movement of turbulent India. At that time, Manto came in contact with Bari Alig. Mr Alig inspired Manto to write against the tyranny of Britain. Manto's first story ‘Tamasha’ (The Joke) was published under a pseudonym in a magazine edited by Mr Alig.

During that period, Manto studied Russian, French, and English literature. He also translated some foreign literature into Urdu, his mother language. The influence of Russian literature is particularly noticeable in his writings.

Manto was involved in various professions throughout his life. Besides editing magazines and writing features, plays for All India Radio, screenplays and dialogues in the film industry of Bombay and Pune, he continued doing many literary works. After the partition, he and his family left Bombay for Lahore in the face of the threat by Hindu fundamentalists.

Stories he wrote

Ayesha Jalal wrote in her book ‘The Pity of Partition: Manto's Life, Times, and Work Across the India-Pakistan Divide’, “Creative writers have captured the human dimensions of partition far more effectively than have historians. Manto excelled in this genre with the searching power of his observation, the pace of his storytelling, and the facility and directness of his language.”

Manto resumed writing shortly after getting settled in Pakistan. But he faced many obstacles there. The Pakistani government not only banned his story named ‘boo’ (The Smell) but also stopped the publication of the newspaper called ‘Nakush’. The story ‘Thanda Gosht’ (The Cold Meat) was also accused of obscenity. At one point, everyone from radicals to Marxist progressives began to oppose him.

When he asked for money, the editor of the magazine extended the pen and paper to write something for the newspaper. Manto started writing again. His drunk eyes kept roaming in every corner from Samrala to Lahore.

He wrote how Titwal's dog ran aimlessly from one side to another side in the Siachen Glacier located in the middle of Hindustan-Pakistan and was shot dead by Jamadar Harnam Singh. He showed a prostitute named Sultana of Delhi is anxious for a black Salwar to mourn in Ashura (the first month of the Muslim Calendar). He penned that Ranadheer was looking for the sweating smell of a dirty working woman who had spent a night with him on the body of his newly married beautiful and educated wife.

Manto wrote that two friends wanted to return a prostitute to her procurer since she was not of another religion, as per their demand. He showed how the Seths lured the Ramkhilawan to kill Muslims. He wrote that Sirajuddin's daughter Sakina unhesitatingly took off her pajamas when the doctor said 'khol do’ (open up) to Sirajuddin to open the window. He had to spend a few months with the lunatics in the insane asylum to write the story 'Toba Tek Singh'.

In Manto's stories, political and social rebellion sometimes took the form of sexual rebellion. He thought that the morality of this rotten society did not lie in sexual purity but sexual repression. As a sensitive writer, Manto tore apart the social and psychological aspects of sexual perversion.

He clearly said: “If you are not familiar with the time we are living in, do read my stories. If you can’t tolerate my stories, do think that this time is unbearable.”

Ismat Chughtai, a famous Urdu writer and a friend of Manto, wrote in her book ‘My Friend My Enemy’ translated by Tahira Naqvi: “I don’t know if Manto actually experienced much of what he wrote about prostitutions, or if his observations were based on his principles and beliefs. I say this because, if he had gone to the prostitute’s kotha, he would have seen the heart of a woman who is a worm from the gutter but who loves life’s inherent goodness. Smashing the scales that have been created to weigh good and bad, Manto created his own scales for these values. Even a perverse and useless person like Khushia (character from the story “Bu”) could experience a sense of honour.”

How the people of Bangladesh evaluate Manto

Javed Hussen, a writer and columnist, has been studying Manto for a long time. He published a translation of Manto’s ‘Siyah Hashiye’ in 2019. He added an essay instead of the conventional preface. He wrote there,

“Manto is second to none in highlighting the multitude of human psyche and ugliness! He observed that everything is altered at any cost as needed when the present turns into the past.”

Researcher Kudrat E-Huda, also a teacher of Bengali language and literature at Shreenagar Government College, said, “Manto was much ahead of his time and unconventional in his writing style. He, being one of the proletariat people, wrote for the same. He wrote about those who are absent and criminals in the eyes of both the state of Pakistan and India.”

Sayeed Ferdous, teaching anthropology at Jahangirnagar University, completed his PhD on “East Bengal/Pakistan episode of the 1947 Partition and its prolonged aftermath in Bangladesh” from Lancaster University, the UK. He said, “Manto's writings reflect the impression of the violence during the partition in human psychology. How the role of the victim and the perpetrator gets tied to the same knot through the violence is captured in Manto's 'Cold Meat' (Thanda Gosht) story. This write-up shows how riots divide the entity.”

The demise of the storyteller

Sanchari Sen, a writer of West Bengal, translated a few of the stories of Manto and published them in a book titled ‘Sadat Hasan Mantor Galpo.’ She added an essay titled ‘Mantonama’ in the preface. She wrote there, “The partition of the country completely devastated some sensitive people. Manto is one of them. His stories written in Pakistan are considered the best but his life in Pakistan was the most difficult. ... Finally, on January 18 in 1955, at the age of forty-two, the word ‘only’ may be placed before the number, left the mortal earth.... Manto did not leave knowing that the movie about Mirza Ghalib, the great poet with whom he identified himself, won the award later. He also deserved the credit for the screenplay of the film. Perhaps he could not have expected that we, the people of this Bengali region, would accept his writing in amazement even today a hundred years after his birth.”

Sadman Sakib is currently pursuing a professional degree at ICMAB.