The entry of a European robot company in Bangladesh eying to automate 3.0 million manufacturing jobs is more than a threat of job loss. In an industry, once one firm starts taking the advantage of robots to replace human workers to reduce cost, competition starts compelling other firms to start increasing robot usages--leading to penetration across all firms of the industry, eventually across all industries and countries.

For centuries, industrial economy has been the ladder for uplifting value addition and income level. Technology progression and public policy triggered the globalisation of manufacturing in 1960s. Over the last several decades, developing countries have been witnessing the conversion of paddy fields into export-oriented manufacturing zones. These factories offered work opportunity to farm workers to become industrial workforce. As a result, labour force has been migrating from agriculture and mining to manufacturing for both higher pay and decent work. Labour cost advantage has been the primary reason for rapid growth of these factories in developing countries. But according to a recent report, it has been observed that the gap between the cost of robot and human labour has been rapidly shrinking, making robot-labour even cheaper than the least costly manufacturing labour force of the world. As machine-labour is becoming a cheaper alternative, upon losing manufacturing jobs, will the factory workers return to their villages to work in farmlands? If so, how should we accommodate this change? Can we create better opportunities for the people losing jobs to robotics and automation in industrial economy?

Over the last 50 years, countries across Asia and also Latin America, lately Africa too, saw sharp growth of manufacturing jobs, primarily due to the technology progression and globalisation. According to the African Development Bank, the continent's manufactured exports doubled between 2005 and 2014 to more than $100 billion. Millions of labour force migrated from farmlands to manufacturing heartlands across the Asian countries. Asia is the largest supplier of low-cost labour to global manufacturing. China alone is home to 100 million labour-intensive manufacturing jobs. Similarly, Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh witnessed rapid growth of industrial jobs over the last couple of decades.

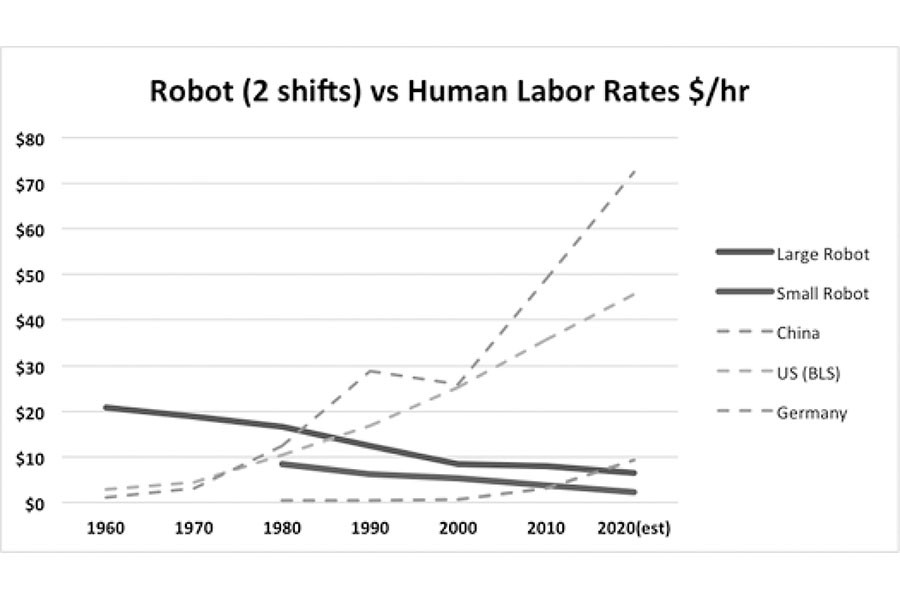

But the same technology progression is raising serious concern. Job division and specialisation has divided production into a series of discrete tasks. Many of these those discrete tasks, involving common operations like pick and place, are now subject of automation, as robots are cheaper to do the job. Robot labour cost, computed as the installed cost of the robot plus tooling and engineering, running 2 shifts at $2-$3 per hour, is now lower than the cost of human labour in China and other low-cost countries across the world. The finding of the recent report referred by the Guardian is highly alarming to observe that "robots are now cheaper than human beings earning $5.0 a day." It translates out that most of the manufacturing jobs in developing countries are vulnerable to automation as these are relatively very simple jobs.???

Automation, in various forms without even having the shape of conventional robots, has been already killing jobs at a rapid space. As a result, the total number of manufacturing jobs has started to shrink. For example, although Bangladesh has been blessed with more than 4 million manufacturing jobs in the textile and readymade garments (RMG) sector, these jobs have started to disappear due to automation. As opposed to 4.4 million jobs in the RMG sector in 2013, current jobs in the sector now stand at 3.6 million. But during the same period, the value of total apparel export from Bangladesh grew from $23.5 billion to more than $28 billion. Those jobs were mostly killed by automation. What are the alternative opportunities of these workers, who mostly left farming jobs to enter into industrial economy, is a serious concern.

Not only the cost of robot is decreasing, but also its capability is rising. With decreasing cost of diverse sensors, particularly digital imaging sensors, and rapid advancement of computing processing capability, it has become technologically feasible as well as economically viable to add smart sensing capabilities to robots. Robots with the capability of sensing and perceiving the environment are now able to deal with variations, and also to cooperate with fellow human workers. This capability has given them a new name: collaborative robots -- opening the window of delegating increasingly complex tasks. As a result, the scope of job delegation has rapidly improved in all major areas: cost, quality and safety.

The rising robot capability to take jobs from human workers is raising serious concern. The economics of producing better products at lower cost with the growing role of robotics is unstoppable. Moreover, for certain countries such advancement of robots has become a blessing, particularly to deal with the ageing workforce. Robotics has been a very timely help in China as a less costly substitute to growing ageing population density caused by one-child policy. For countries with pyramid shaped demographic distribution, like India or Bangladesh, robot as a substitute to low-cost labour is a serious concern. Does it mean that the opportunity of labour force migration from farming to manufacturing is basically coming to end? If that is the reality, what are the possibilities for these countries to find alternatives to deal with the situation? Upon losing factory jobs, what will those factory workers do?

The decreasing cost of robot to perform repetitive manufacturing jobs is raising the vital question: are we at the cusp of reverse labour force migration? But neither agriculture nor mining needs more labour, they need advanced technology-based innovations to turn farming into high-tech productive activities to support sustainable wealth creation. How to balance profit making and job loss due to robots, and create alternative opportunities is a major policy challenge for the development planners and policy makers.

M Rokonuzzaman Ph.D is academic, researcher and activist on technology, innovation and policy. [email protected]