We have long speculated on the moment when the shift of global leadership from the United States to China would take place. From Washington to Beijing for the political power, from New York to Shanghai for the economic one. It seems that we are witnessing it now.

Some saw the Beijing Olympics (2008) and especially its opening ceremony as an attempt by China to display this new reality. Others saw it later, with the creation of the Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (2015), as opposed to the Bretton Woods system (IMF and World Bank) that for decades has been a fundamental pillar of North American hegemony.

A certain truce came with Obama and Xi Jinping, with some sort of a de facto confirmation of a new bipolar global regime. A regime that, even if temporary, could punctually have some positive effects for global governance, such as the two leaders' pact on climate change that made the Paris Agreement feasible, also in 2015.

However, with the arrival of Trump and his "Make America Great Again", the escalation of this quarrel for global leadership increased in both speed and visibility. The most relevant examples, so far, are the trade war between the two countries - with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) as a hostage; or the open battle over the control of 5G, with the Huawei controversy at its the core.

Other examples are less obvious to general opinion, but a matter of debate in specialised settings. An example is the full-fledged offensive that China has made to increase its presence and influence in the multilateral system - obtaining important first-level positions, but also second level postings key to influence these institutions, in the face of the neglect of the early years of the Trump administration.

One case is that of Geneva, where the US administration has vacated for more than three years the position of ambassador of this key place, the city with most diplomatic activity in the world. Three long years has taken to the State Department to realise the space that China and other powers were gaining by taking advantage of the US "empty seat" policy.

They did so by appointing a new high political-profile ambassador in November last year. However, the positions of the battles for the future of the WTO or the leadership of the International Telecommunication Union (key in the management of satellite orbits, the management of radio space or digital world governance) were already well advanced at that time.

History is capricious, and again the unexpected ends up precipitating Copernican changes. No one expected the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 with the chain of fatalities that would follow.

Nor could be expected that a clumsy press conference on the afternoon of November 09, 1989 would lead to the Berlin Wall immediate collapse; something that none of the Western intelligence agencies had anticipated.

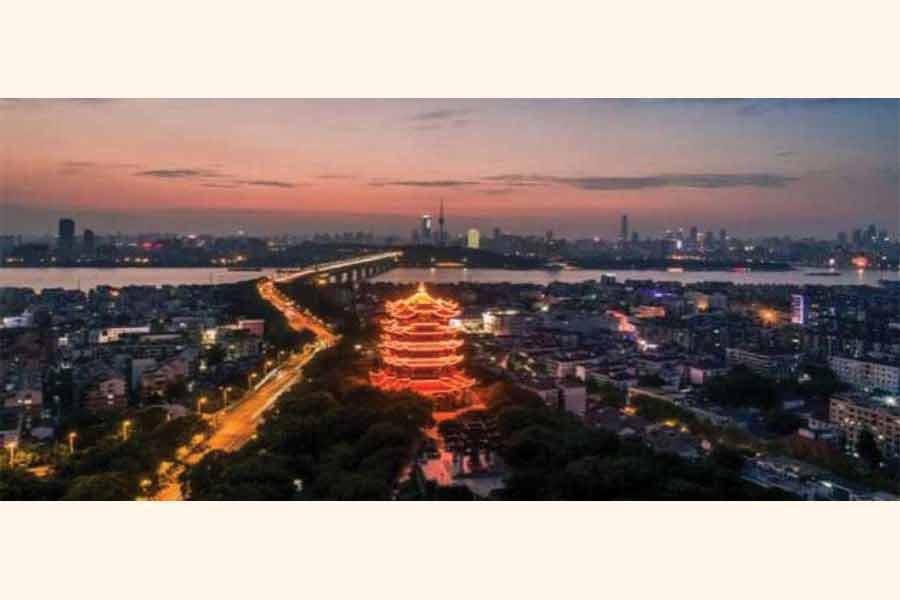

Then, between November and the beginning of last December something happened in the Huanan market, in the city of Wuhan. It seems that the first case occurred on November 17. But it was not until December 31 that an "outbreak of an unknown pneumonia" in this city was reported to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The Huanan market was closed down on January 01. The following day the new virus was confirmed, with the technical name of SARS-CoV-2. On January 16, Japan reported the first case, on the 17th, Thailand did.

The 21st was Taiwan and the United States. On the 24th, France reported the first three cases within the European Union (EU), the number of countries increased as the first border closures took place, especially in countries bordering China.

On January 30 the WHO declared an International Public Health Emergency, the same day that Italy reported its first case; the next day it was Spain at the same time that the virus was already spread in India, Russia, the Philippines or Australia. On March 11 the WHO declared the global pandemic and, while the world trembles, global leadership transits.

On March 20, while the White House or Downing Street were still flirting with denialism in relation to Covid-19, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced a plan to support 82 countries in their fight against this virus.

Two weeks later, as the virus wreaked havoc on hospitals on both coasts in the United States, and the British Prime Minister was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), 18 countries in central and western Africa had already received hundreds of tons of Chinese donations of medical supplies, and 17 more were waiting to receive them in a matter of days. Pakistan, South Korea, Spain or Italy are other countries that have received help. In the latter, this help was not only of material, but accompanied by experts and medical staff.

Putin's Russia also took advantage of the pandemic in the first weeks to project its role as international power; by sending military personnel to Italy - in a context of astonishing silence and blockage of the European institutions - or aid in health supplies to his "friend" Trump.

And even as Covid-19 spreads through Moscow and other cities and regions of the Federation these rather symbolic activities continue. Turkey also tried, by responding to Spain's NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) urgency request, but soon changed its policy once they realised how the situation was deteriorating in Ankara and Istanbul.

It is too early to evaluate the full scope of Covid-19. In fact, no one can really assert at this point what the evolution and global impact of the pandemic will be, neither in terms of public health, nor in its humanitarian, social or economic dimensions.

The outlook is not good, and particularly worrisome is the uncertain effect that this pandemic will have in less developed countries, considering how it is affecting higher-income ones.

However, it is quite clear that this will be a turning point in terms of global governance and hegemony. Once again, the arbitrariness of history precipitates change. The strategists, the intelligence agencies, the think tanks that for years have debated and conspired from Langley through Georgetown, Xijuan or Gouguan had not foreseen what would end up igniting in a provincial market in Wuhan.

But what does seems plausible is that, in the midst of such drama, we are witnessing the hanging over of global hegemony.

Manuel Manonelles is Associate Professor of International Relations, Blanquerna/University Ramon Llull, Barcelona

—Inter Press Service