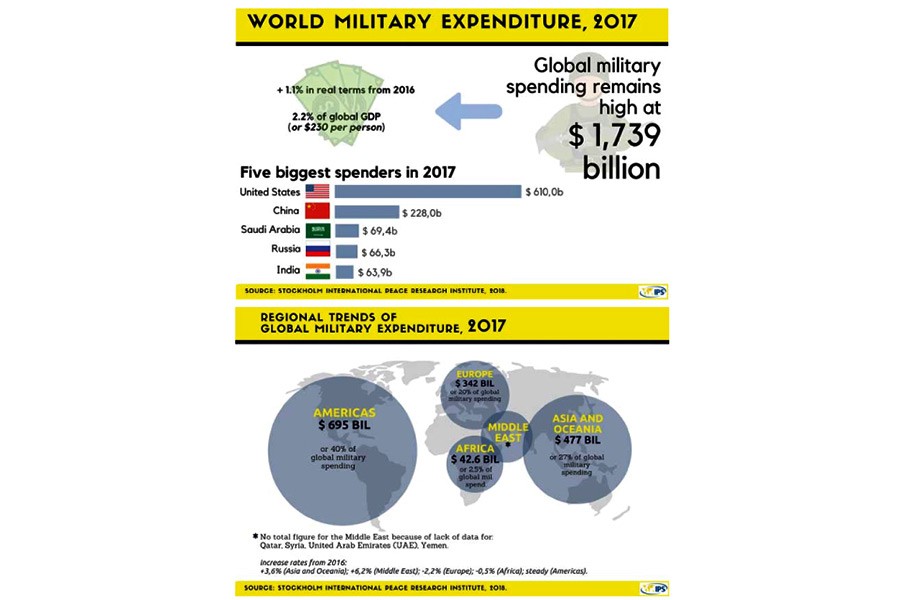

According to the latest report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), in total, countries around the world spent $1739 billion on arms in 2017. Although there was a marginal increase of 1.1 per cent rise in real terms on 2016, the total global spending in 2017 is the highest since the end of the cold war.

This is an unprecedented amount of resources. The spending in 2017 represented 2.2 per cent of global domestic product (GDP) or $ 230 per person. The 'military burden', which is "the military expenditure as a share of GDP" and which "assesses the proportion of national resources dedicated to military activities and the burden on the economy", has fluctuated from a post-cold war high of 3.3 per cent in 1992 to a low of 2.1 per cent in 2014.

The five biggest spenders in 2017 were the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, Russia and India, which together accounted for 60 per cent of global military spending. The United States alone accounted for more than a third of the world total in 2017 ($695 billion) and it spent more than the next seven highest spenders combined, confirming the fact that the country can retain itself as the most powerful nation - in terms of military - in the world.

Looking at the US trend, there is a clear difference between the Obama and the Trump administration. US military expenditure had fallen each year since 2010 and substantially did not change in 2017 from 2016. However, the military budget for 2018 has been set by the Trump administration at a considerably higher level ($700 billion).

REGIONAL TRENDS: Looking at the regional trends, in the Middle East, because of a lack of accurate data for Qatar, Syria, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Yemen, SIPRI could not estimate the total military spending in this region in 2017. Between 2009 and 2015, military expenditure of countries in this region increased by 41 per cent, although it then decreased by 16 per cent between 2015 and 2016 because of the fall in oil prices.

The spending increased again in 2017 by 6.2 per cent with Saudi Arabia being the largest military spender in the region and the third largest in the world, following the US and China. Turkey increased its military expenditure by 46 per cent between 2008 and 2017 while the last available estimate for the UAE's military spending is for 2014, when it was the second largest military spender in the Middle East ($24.4 billion). After some years of decline, Iran could increase its military spending between 2014 and 2017 by 37 per cent, mainly due to the gradual lifting of European Union and United Nations sanctions, which brought benefits to the Iranian economy. Israel's military spending increased by 4.9 per cent to $16.5 billion in 2017 (excluding about $3.1 billion in military aid from the USA). Today Israel is one of the 10 countries with the highest 'military burden' in the world (4.7 per cent of GDP).

Military spending in Asia and Oceania reached $477 billion in 2017, a 3.6 per cent higher than in 2016 and 59 per cent higher than in 2008. These high levels make the region the second largest spender after the Americas. The largest increases in military spending between 2008 and 2017 were those of Cambodia (332 per cent), Bangladesh (123 per cent), Indonesia (122 per cent) and China (110 per cent). China's military spending in 2017 ($228 billion) accounted for 48 per cent of the regional total.

Europe accounted for 20 per cent of global military expenditure in 2017, at $342 billion. The spending in Europe was 2.2 per cent lower than in 2016 and marginally higher (1.4 per cent) than in 2008. France's spending fell by 1.9 per cent to $57.8 billion; the British military spending rose by a tiny 0.5 per cent to $47.2 billion, while Germany's spending rose by 3.5 per cent to $44.3 billion, its highest level since 1999.

In Africa, military expenditure was marginally down in 2017, by 0.5 per cent to $42.6 billion or 2.5 per cent of global military spending. North Africa's military spending was an estimated $21.1 billion in 2017: the first annual decrease since 2006. Algeria, Africa's largest spender, decreased its budget by 5.2 per cent between 2016 and 2017 to $10.1 billion. Nigeria's expenditure fell for the fourth consecutive year in 2017, despite the ongoing military operations against the terrorist group Boko Haram. Its spending was $1.6 billion in 2017.

MILITARY EXPENDITURE VS AID TO DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: These data, combined with other key information on budget spending from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), show that the portion of GDP that OECD countries spend every year for the military, is much higher than the one dedicated to the 'Official Development Assistance' (ODA). The latter is defined as "government aid designed to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries". According to OECD, "loans and credits for military purposes are excluded [from ODA]" and this aid "may be provided bilaterally, from donor to recipient, or channelled through a multilateral development agency such as the UN or the World Bank".

The gap between military expenditure and ODA in OECD countries is incredibly deep in most cases. For example, Turkey spends more than twice as much for its military budget rather than for aid to developing countries: 2.2 per cent of GDP for its military and 0.95 per cent for ODA. The gap is even greater in the case of Israel: 4.7 per cent for the military budget and an insignificant 0.10 per cent for ODA. The US spends 3.1 per cent of its GDP for the military and 0.182 per cent for ODA. Only a few countries follow the opposite trend. Luxembourg, for example, in 2017 spent twice as much for ODA (1.00 per cent of its GDP) rather than for its military budget (0.5 per cent).

Analysts, activists and policymakers worldwide have often criticised this allocation of resources. Regardless of the freedom of each country to spend its budget in the way it prefers in order to guarantee security for its citizens, there is an important aspect to note. Anton Chekhov once said: "If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise, don't put it there". This principle, which then took the name of 'Chekhov's gun', was paraphrased as "once a gun appears in a story, it has to be fired", someday soon.

A global military expenditure of over $1.7 trillion clearly represents much more than a simple "pistol on the wall". The likelihood to have a conflict caused or fuelled by those arms produced by that $1.7 trillion global budget, is higher than ever.

-Inter Press Service