In Bangladesh, it is reasonable to assess the budgetary allocations from a pro-poor perspective. Latest government estimates show that, in 2018, 21.8 per cent or nearly 36 million of the country's population live below the poverty line; and 19 million of them are extreme poor. The government plans to reduce poverty to 12.3 per cent and the extreme poverty rate to 4.5 per cent by 2023-24.

The medium-term policy strategy underlying the FY2019-20 budget is to achieve a growth rate of 10 per cent by FY2023-24, and maintain that rate until 2041 to build a solid foundation of a high income country. Further, the goal is to enhance the competitiveness of all sectors to reduce poverty, generate employment, and attract foreign investment.

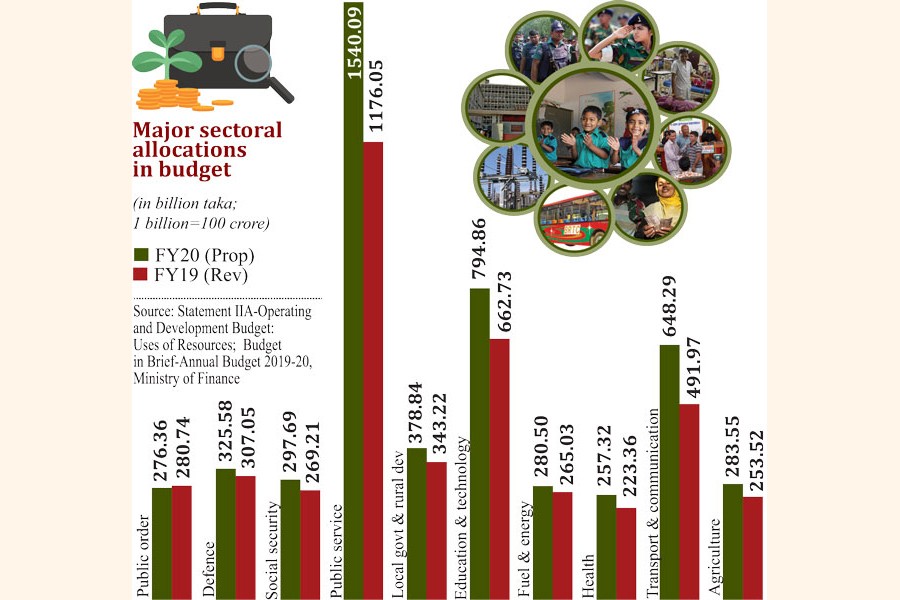

In the budget, regional parity, human resource development, infrastructural development, and quality of expenditure have been given priority. The FY2019-20 budget sets total expenditure at TK 5231.90 billion (523,190 crore), which is 18.1 per cent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). Total allocation for operating and other expenditures is TK 320,469 crore, and allocation for the annual development programme (ADP) is TK 2027.21 billion (202,721 crore). The ADP allocates 27.4 per cent for human resources, 21.5 per cent for agriculture and related sectors, 13.8 per cent for power and energy, 26 per cent for communications, and 11.3 per cent for other sectors. For reducing poverty and income inequality, policy emphasis in the budget is on expanding the coverage of social protection programmes, employment opportunities, microcredit, and efficiency enhancement trainings.

GROWTH OF POOR AND VERY POOR PEOPLE'S INCOMES: Despite the emphasis on social protection, the budget policies do not seem to have paid much attention to the growth of poor and very poor people's incomes, which depends on productive asset accumulation in agriculture and the non-farm economy. Making financial services accessible to the poor and the very poor and ensuring their productive use is a priority, as are measures which ease access to productive assets and equipment. Asset possession underlies resilience against shocks. It is the absence of assets which makes people especially vulnerable. As such, protecting assets is a priority. This may be achieved through social protection, but also through multiple and specific policies such as productive resource conservation, price stabilisation schemes, or insurance linked to financial services.

The poor operate in the low-end segments of labour, service and commodity markets where the returns are low. Getting people from poor households into higher return markets through skills upgrading, and tightening of these markets are two ways of facilitating the escape from poverty.

SOCIAL SAFETY NET PROGRAMMES: There are many categories of people who are especially vulnerable, usually to several sources of risk, and who need broad protection: households mainly dependent on casual wage labour; women-headed households (separated, divorced, and widowed) and their dependents; socially excluded women; older people, the chronically ill; and similar other vulnerable groups. Well-designed social assistance would support the greater involvement of these groups in growth and accessing health and education services, the latter especially important for interrupting inter-generational poverty.

So far, nearly a quarter of the families have been covered under the social safety net programmes. With a target of doubling the allocation for social security over the next five years, the FY2019-20 budget allocation is TK 743.67 billion or 74,367 crore (compared with TK 644.04 billion or64,404 crore in the revised FY2018-19 budget) which is 2.58 per cent of GDP. The portfolio of programmes include allowances for population groups with special needs, food security and disaster assistance programmes, public works/employment programmes, and programmes focused on human development and empowerment.

INEQUALITY INCREASES IN THE RURAL AREAS: It is now widely recognised that inequality can undermine development, poverty reduction and growth in a country like Bangladesh. There seems to exist a positive association between income inequality and income poverty, material deprivation, and multidimensional poverty. The mechanisms which drive this relationship are no doubt complex and cover social, economic, spatial, and political dynamics and even crimes (e.g. drugs) particularly those that have the potential for economic gain. To reduce inequality, there is a need for a more inclusive growth pattern, changes in social norms, and redistributive policies.

Further, the usual focus of political parties is on policies that favour the voting electorate who are less likely to support redistributive (or 'pre-distributive') policies so as to gain support of the rising rich and powerful elite and avoid political instability. But evidence supports the view that to reduce poverty, it is also necessary to tackle inequality. In Bangladesh, distribution is central to fighting poverty; and distribution objectives should be an integral part of the poverty reduction agenda. Although the relative importance of growth and distribution varies across countries and the growth effects dominate in most cases, but distribution can have a significant effect in Bangladesh.

Over the period of 1964-2016, national Gini of income distribution in Bangladesh has risen from 0.360 to 0.483; the rural Gini increased by nearly 38 per cent and urban Gini by 21 per cent over the same period. Thus overall inequality increased rather sharply in the rural areas, while urban areas experienced somewhat moderate rise in income inequality.

The Palma ratio (ratio of the richest 10 per cent of the population's share of gross national income divided by the poorest 40 per cent of the population's share) suggests that 'middle classes' (defined as the five 'middle' deciles, 5 to 9) - tend to capture around half of gross national income (GNI) almost universally. The other half of national income is shared between the richest 10 per cent and the poorest 40 per cent. In Bangladesh, it is changes in these extremes that are most noticeable; while the share of income in the middle is relatively stable. The Palma ratio at the national level has consistently increased in Bangladesh from 1.68 in 1964 to 2.93 in 2016; in urban areas, it rose from 2.00 to 2.96 while, in rural areas, it grew from 1.38 to 2.51 over the same period.

This shows that while the poorest 40 per cent generally loses in terms of income share, the richest 10 per cent gains in Bangladesh. The policy implication is that Bangladesh should focus on its 'extreme' inequalities, that is, inequalities that do most harm to inclusive and sustainable growth and undermine social and political stability. Although Bangladesh is richer than ever before today, the richest 5.0 per cent of the households receives nearly 28 per cent of the total income, while the bottom 5.0 per cent gets only 0.23 per cent.

LOPSIDED PUBLIC EXPENDITURE AND A REGRESSIVE TAX SYSTEM: This year's budget differs only marginally, it seems, on where to allocate public spending. From a poverty perspective, the important issue is: do we have lopsided public expenditure and a regressive tax system in the budget? At the aggregate level, spending on areas as crucial as health and education remains mostly static, whether looked at as a proportion of GDP or as a proportion of total government expenditure. The FY2019-20 budget makes an allocation of 7.2 per cent of total public expenditure for local government and rural development relative to 7.8 per cent in revised FY2018-19 budget; 15.2 per cent (including Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant) for education and technology compared with 15.0 per cent in the earlier fiscal year; 4.9 per cent in health relative to 5.0 per cent in FY2018-19; and 5.6 per cent in social security and welfare in the coming year relative to 6.0 per cent in the last fiscal.

In contrast, expenditures on public services have jumped from 15.3 per cent in the last fiscal to 18.4 per cent in this year's budget; on transport and communications from 11.1 per cent to 12.4 per cent; and on interest payments, expenditures remain mostly static at around 11 per cent.

For the poor, sectoral allocations with programmes that directly target the poor people are important. Under the health sector, this includes universal health coverage including child and maternal healthcare. Under the education sector, allocations to basic education, specifically free primary education programmes and school health and nutrition are important. Budgetary allocations to social protection, namely cash transfer to vulnerable groups, including orphans and vulnerable children, older people and people with disabilities are also important.

The Health Services Division and Health Service and Family Welfare Division of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare have received TK 257.33 billion or 25,733 crore (4.9 per cent of total allocations) in FY2019-20. The goal in the health sector is to ensure affordable and quality health and family welfare services for all. A sector-wide programme has been adopted for implementation during 2017-2022 under 29 operational plans. Providing nutrient foods and health services to mothers and children, quality general and specialised health services for all, control of communicable and non-communicable diseases and diseases caused by climate change, development of modern and efficient medicine sector and skilled manpower are included under the programme.

One of the government's medium-term priorities in the health sector is the scaling up of universal health coverage including maternity health services, subsidies for poor and vulnerable groups and reducing out-of-pocket health expenditure. Further, the government intends to develop a national health insurance scheme as a health sector flagship programme to promote equity in healthcare financing. This is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG3 urges countries to achieve universal health coverage by 2030 including 'financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all'. Community clinic is the first service centre to provide primary health services to the rural people. With 13,779 operational community clinics, rural women and children get basic health services.

With significant progress achieved in promoting primary education, the focus now is on providing education supportive of bringing about fundamental changes in the living standards and on creating better learning environment at schools. The emphasis is on following rules of personal hygiene and maintaining cleanliness of surroundings, morality, discipline and responsibility, life skills and mutual responsiveness.

Various measures are included to ensure quality and universal primary education covering nationalisation of 26,193 private primary schools, enactment of the Non-Formal Education Act, distribution of stipends through mobile banking, improvement of infrastructures in the newly nationalised and existing primary schools, distribution of free text books, supplying computers and multimedia to schools, and improvement of various education related infrastructure. A total of TK 240.40 billion (24,040 crore) has been allocated for the primary education sector, which was TK 205.21 billion (20,521 crore) in the FY2018-19 budget.

Science and technology-based secondary and higher education is the priority of the government including expansion of quality secondary education, among which training for secondary school teachers, construction of classrooms in academic institutions in underdeveloped areas, providing stipends among poor and meritorious students are important. The allocation for the secondary and higher education sector is TK 296.24 billion (29,624 crore) which was TK 258.66 billion (25,866 crore) in the current fiscal year. Initiatives have been taken to set up technical schools and colleges at the upazila level and modernise madrasa education. The proposed programmes are critical to achieving SDG4 -inclusivity in learning opportunities.

For eliminating unemployment by 2030 through generating employment for 30 million (3 crore) people, a three-year programme has been taken up to increase job creation in the industrial sector by improving business and investment environment, ensuring protection of workers, and reforming the legal and regulatory framework. The budget allocates TK 1.0 billion (100 crore) for training and employment of specific groups of people.

For creating jobs for the unemployed youths and generating self-employment opportunities, skill development trainings are provided to youths through 111 formal training centres across the country and 498 training centres at the upazila level. The FY 2019-20 budget allocates TK 1.0 billion (100 crore) to provide start-up capital to promote all types of startup enterprises by the youths.

Apart from involving the poor in regular economic activities, social protection programme has been adopted as one of the tools to fight against poverty and inequality. Following the 7th Five Year Plan (2016-2020), every year the coverage and scope of the main programme is being expanded for the marginalised and most vulnerable segment of society. The country's disaster-prone and ultra- poor regions are given priority while allocating resources.

Along with raising the rate of allowances and widening the beneficiary coverage, efforts are taken to introduce ICT-based reform programmes including G2P payment method to make the social protection programmes target-oriented, transparent and accountable. Besides, digital database integrated with national ID has been developed for every social security programme to prevent duplication in beneficiary selection.

In line with the 7th Five Year Plan, the government is implementing pro-poor programmes for universal health coverage, universal access to basic education, and cash transfers to vulnerable groups including older people, disabled people, orphans and children as well as food insecure households. Compared with previous financial years, almost all the programmes favouring poor and vulnerable groups have been allocated more resources. However, there is a gap between actual allocations and resource requirements to ensure full coverage and create sustainable impacts. Deficits in allocations are observed in all programmes targeted to the poor and disadvantaged people. Further, implementation capacity in the respective sectors is low, which have negative implications on the quality of services. Overall, pro-poor sectoral and programme allocations are yet to take the centre stage in the national budget.

Regarding revenue mobilisation, the actual performance in FY2017-18 gives a figure of TK 2165.55 billion or 216,555 crore (9.6 per cent of GDP) which is projected to rise to TK 3778.10 billion or 377,810 crore (13.1 per cent of GDP) in the budget of FY2019-20. The Finance Minister has also expressed his determination to raise it to 14 per cent of GDP over the next two years which would imply a revenue mobilisation of about TK 4593.73 billion or 459,373 crore in FY2020-21. For the purpose, the budget has proposed massive reforms in the revenue administration, business-friendly tax rates, prevention of mismanagement, corruption and misuse in the tax revenue management through automation.

The number of income taxpayers is only about 2.2 million although there are about 40 million people who are included above the middle income groups. The budget intends to take this number to 10 million at the earliest possible time. Efforts to bring the rest of the citizens under the tax net will continue; but until that happens, these few millions will be the only ones who will be required to pay income tax. And, they number only 1.3 per cent of the total population.

Given the low tax-GDP ratio, it is no doubt important to raise the country's tax levels with tax reforms. But before this additional fiscal space is created, there should also be a clear understanding of how the fiscal space will be used and how the additional tax burden will be distributed. There must also exist public institutions that are capable of enforcing the policies in a competent, efficient and corruption-free manner. In most cases, the costs of tax increase tend to be more certain than the benefits from higher public spending in Bangladesh. In the present situation, it would be better if higher revenues could be obtained from a truly progressive income tax that would bring more equity to the tax system. This could be supplemented by higher taxes from widening the base of the value added tax.

We should note that everyone pays indirect and other taxes and duties which the producers can pass on to the consumers. In fact only about 27 per cent of the government's total tax revenue comes through direct taxes. In the budget speech of FY2017-18, the then Finance Minister hoped to raise this share to 50 per cent -- a difficult task and ambitious target but not impossible. In that speech he also stated a three-pronged strategy. These were: (i) continuity and stability of tax policy; (ii) transparent enforcement procedures; and (iii) simplified business operations. But nothing much has been achieved. Enhancing income tax share means increasing direct tax and ultimately making it much higher than indirect tax. The current 27:73 ratio of direct and indirect tax needs to be gradually reversed to uphold the interest of the consumers and the productive sectors.

Obviously, a big issue in the tax system is that of tax evasion and avoidance on the part of big businesses and rich individuals. The impact of tax evasion on the poor households is that revenues that would be used by the public sector for development assistance, transfer funds, employment creation, services and other investments are lost. It is of concern because it is a symptom of weak institutions and poor policies; it thwarts sustainable development and poverty reduction. Also there exists the issue of providing 'subsidies' to the rich through various tax and duty adjustments. The budget documents should include a 'statement of revenue foregone' because of such measures making it easier to track these subsidies for the rich.

With acute income and wealth inequalities, the question remains whether the government has the ability to enforce wealth taxes on the country's elite that have a vast arsenal of tools to avoid and evade taxes. Wealthy individuals often have access to sophisticated tax sheltering strategies and may reduce their tax burden by offshoring assets to tax havens. The Panama Papers reveal offshore entities are used by many wealthy individuals even from low income countries.

Wider coverage of third-party reporting, coupled with systematic cross-validation of reported information and increased scrutiny of high net worth taxpayers, can strengthen enforcement capacity of the tax administration. Voluntary disclosure schemes help collect new information about assets and income and generate more revenues from wealthy taxpayers. For such programmes to be effective in improving compliance in the shorter and longer term, strict enforcement needs tough noncompliance sanctions and a credible threat of detection. With better enforcement, wealth taxes can complement progressive income taxes to reinforce progressivity and address inequality in the context of Bangladesh where elites are difficult to tax.

Mustafa K. Mujeri is Executive Director, Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development (InM)