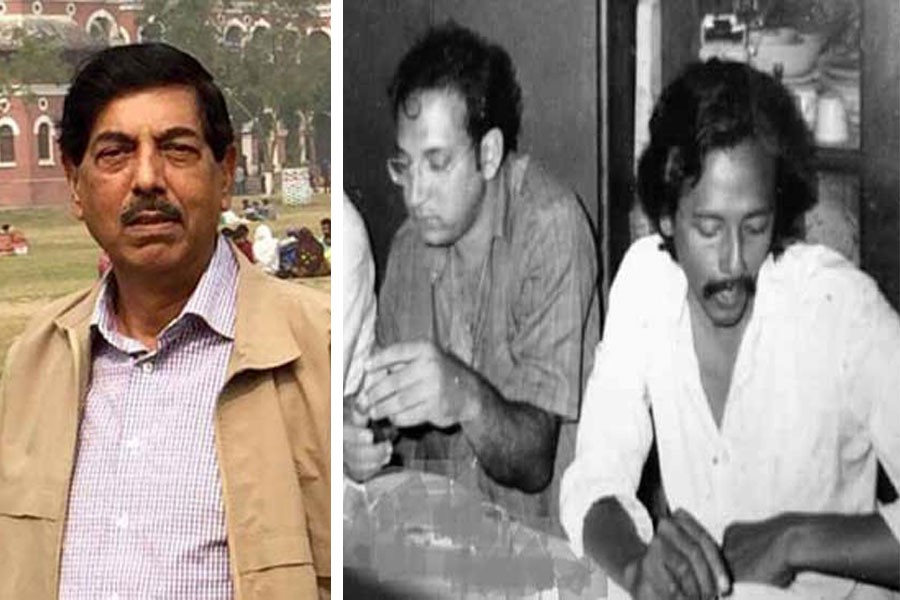

People like Zillul Hye Razi are not found too often. Razi passed his life from youth to his sudden death at 66 on November 27in style. It was unique to him. Apart from the folksy way he appeared to his friends and associates at the mundane level, he also proved in his death that he was different from others. He was health-conscious and had always been caring about his friends and the close ones. His vast reading and the tendency to keep abreast of the latest developments in every field, including medical science, does not go with his death from a cardiac arrest. It was his first, and a massive one at that. Despite his warmth and friendliness, Razi used to nurse a private self. It was his favourite recess flooded with the light of knowledge. Few were able to fathom it, and fewer still were qualified enough to have access to it. Given this, at the age of 66 Razi was not aware of the fact that he might fall victim to a heart attack anytime, and thus should keep the physical vulnerabilities at bay is a great riddle to many. The most shocking part of Razi's passing-away was he had been on the Facebook just an hour before his heart failure.

To his friends and admirers for nearly forty years, including this writer, Zillul Hye Razi was lovable and unpretentious. At the same time, he was a person with self-dignity as well as respectful of the importance of others. He could be defined as the epitome of civility and the virtues clean and heartening. Razi's total mien and the individual way of viewing life and things around were not supposed to fit him into the noisy and often-raucous ambience of the gossip venue called Rekhayon. Many would like to ascribe this attraction of Razi for the place to his latent passion for creativity and the arts. A number of the Rekhayon visitors were engaged in practical journalism, and would love to talk current affairs. Razi found in them a medium of testing the credibility of his own observations on many global issues.

Rekhayon was a well-known venue in the capital for idle gossip and informal discussion on creative activities in the 1970s-early 1990s. Had it not been located at a roadside in Dhaka's Shahbagh area, it could well have been passed for an indigenous salon --- like the ones in Paris in the 19th and 20th centuries. The day and late night-long 'adda' at Rekhayon, basically a centre of commercial painting, had almost every feature that distinguished the literary and cultural assemblages in Paris. Tea or coffee, accompanied by occasional nun-kebab, pure gossiping, poetry readings, discourses and debates --- the essential components of a lively salon --- would be found at Rekhayon. Raghib Ahsan, a self-made artist and aesthete now living in the USA, ran the whole show as the owner of the art shop. Many, including Razi and a few others, would like to call Rekhayon a street-side boulevard café like those seen also in Paris. No matter how people would define it, Rekhayon managed to keep its youthful character for years on end. In those days, scores of Dhaka young ladies used to attend art and literature-centred gossip sessions. Rekhayon, too, had its lady poets, artists and intellectuals.

Dhaka has not had any dearth of youth hangouts. Nor has anyone ever felt that there would be any gap in the future. In every part of the city, vibrant youths and seemingly ever-green middle-aged people would be seen launching their own 'addas' or relaxed gossip sessions. By the mid-1970s, the golden age of the proverbial cultural haunts of Beauty Boarding, the restaurants of Rex, Gulsitan, etc., had been on the wane. After that the new-generation outlets for buoyant youths bubbling with creativity, new ideas and entrepreneurship kept coming up. As the capital stepped into the decade of the seventies, it entered its second golden age in its tradition of leisurely gossiping, 'addabaji' in Bangla. Youths involved in cultural and literary, also scholarly, activities literally had their heyday in Dhaka forty-five years ago. As part of a universal rule, no `golden age' is everlasting. The duration of some is too short; some begin petering out after a comparatively longer period of existence. The truth, however, is one day all such sessions will have to call it a day. Among these 'addas' in Dhaka in their second golden age, Rekhayon was able to stand out with its uniquely striking features.

Located on Elephant Road near today's Aziz Supermarket in the then tranquil Shahbagh area, Rekhayon hosted a localised hangout frequented mainly by young poets and short story writers and artists. A section of little magazine editors were also regular visitors. Most of them were students of Dhaka University and the erstwhile Dhaka Art College. Fresh entrants to professions like journalism, teaching, art work and copywriting, as well as film society activists would also comprise the crowd time-outing there. Moreover, university dropouts, jobless youths, and thus free like a bird, used to constitute a sizeable segment. One remarkable feature had made the Rekhayon 'adda' different from the others: most of the people there directly and indirectly were involved with either literature or other branches of the arts.

Unlike Dhaka's other 'addas', the one at Rekhayon had no time-schedule. It would open in the morning and its shutters would be pulled down late into the night. Its door remained wide open to anyone interested in creative activities. Beginning in the 1970s and continuing through the mid-1990s, the morning to late-night gossip sessions would welcome everyone. In spite of the dominance of young authors and artists, Rekhayon always took pride in the presence of a few brilliant youths. They did not write or paint. But their erudition and polished nature would add to the shine of Rekhayon. Zillul Hye Razi was one such young man. All of them had their own distinctiveness. In the seventies, like many of us, Razi was a student at Dhaka University. He passed out with Masters in Economics in 1974. A meritorious student all through, he joined the Dhaka office of the European Union in 1989. After serving there for 26 long years, Razi retired as trade adviser to the Delegation of the European Union in Bangladesh. He was also a member of the management committee of the Ispahani Islamia Eye Institute and Hospital Bangladesh.

Remaining engaged in talking without any specific subject, interspersed with quips and sardonic remarks on certain persons, defines a typical Bengalee `adda'. It has been so since the spread of urban culture in this part of the South Asian region. At the Rekhayon gossip sessions, Razi's role chiefly was that of a patient listener. He loved to watch others talking, getting emotional and excited at times, without normally participating in those. He appeared to have nursed an inherent gift for mediation and peace brokering. This quality of Razi has prevented many tiffs from snowballing into bitter face-offs. In spite of his scholarship accompanied by a reserved air, his subterranean blithe temperament would not remain hidden. This writer has never seen him making fun of anyone present, but he had an enviably rich stock of jokes. Razi's sense of humour and the witty comments endeared him to both younger and senior visitors to Rekhayon. Before he joined his EU job, his afternoon and evening presence at the venue was an everyday routine. Had Rekhayon's 'adda' been in place today, Razi's friends would have to grope for the appropriate words to express their shock and grief over his untimely death.