Current trends indicate that the global economic recovery is on - albeit unevenly. Although growth looks to be a bit rapid in many emerging economies like the member countries of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), it still remains fragile in most advanced economies. In fact, the global economy continues to improve amidst ongoing policy support and improving financial market conditions. As the latest trends indicate, the world trade continues to pick up gradually, and in many developing regions, the trade volume has almost returned to the pre-crisis levels owing to the robust growth in some large developing economies - mainly India and China, and the restocking of inventories.

THE TALK OF THE TOWN: Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of natural and mineral resources. The land is so fertile, it could be one of the world's largest exporters of fruits and vegetables (at the moment it is one of the largest importers). People say that you can almost just throw seeds on the ground and they will grow, yet a significant part of the population, ranging between 50-70 per cent, do not have enough food to eat and remains malnourished. In terms of mineral wealth, in some parts of the country the story goes that you can pick up a handful of earth and almost sift diamonds and precious metals through your fingers. It has water in abundance; you can sink a well almost anywhere, yet the majority of the population has no access to safe, clean drinking water.

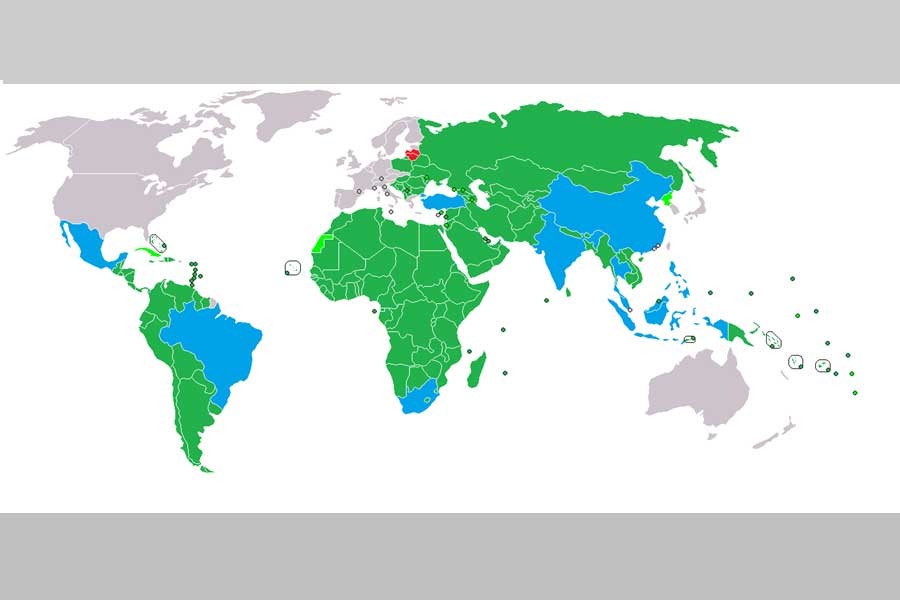

BRICS, coined by US investment bank Goldman Sachs to describe the five key emerging economic powers, has been predicted to account for an increasingly greater share of the world economy, which accounts for around 22 per cent of the global economy - compared to 16 per cent only a decade back. Though Russia (the world's largest gas and oil producer) fell into its worst recession in the very recent past, the economy is still expected to grow in 2018 - mainly by a rebound of oil prices. While dollar-denominated assets were held heavily by China with the US Treasury, Brazil, which slipped into recession a couple of years back, rebounded and grew thereafter with the ability to become a major player tomorrow in the world economy after locating huge deep sea oil reserves. India is expected to post over 7.0 per cent growth this year - mainly backed by consumer and government spending. Economies like Bangladesh, Vietnam, South Korea, among others, are also steadily coming up.

DEVELOPMENT ROUTES ARE NOT THAT REPETITIVE: The latest trend has been that the new financial plumbing are in the making. London and New York are not about to lose their spots as the world's leading centres, and they are being increasingly challenged by emerging market upstarts in a potentially lucrative area - management of fund being cut well away from the traditional centres. If the recent trends are any indication, spur of growth of financial centres in the fastest-growing economies would be there in view of prominent factors like rising trade between emerging economies, cross-border mergers, and acquisition by some companies as well as move by developing world businesses to raise capital in each other's markets.

Capital is much more efficiently deployed in comparatively less risky emerging markets where the returns are higher. The intra-emerging market movements of funds are quite evident - flows between Africa and India, India and China, and India and Korea have been on the rise. Singapore is challenging Switzerland for the world's wealth management business while Hong Kong, which led the world in IPOs (initial public offerings) several years back, has been an upcoming centre as an equity hub for Asia's growing resources companies.

At the global level, these are being considered as seeds of a new model, being the one in which the savings of emerging markets flow to the areas showing highest growth rates and not to the US and Europe.

HEAVY TASKS AHEAD: Obvious enough is that the declining share of manufacturing jobs in overall employment has been a concern for policymakers and the broader public alike in both advanced economies and some developing economies. The IMF (International Monetary Fund) is prompt enough to caution that although manufacturing plays a unique role as a catalyst for productivity growth and income convergence and a source of well-paid jobs for less-skilled workers, yet in many countries, manufacturing appears to have faded as a source of jobs. Its share in employment in advanced economies has been declining for nearly five decades now.

Accordingly, in developing economies, manufacturing employment has been more stable. But among more recent developers, it seems to be peaking at relatively low shares of total employment and at levels of national income below those in market economies that emerged earlier. The share of jobs in the service sector has risen almost everywhere, replacing jobs in either manufacturing (mostly in advanced economies) or agriculture (in developing economies).

Clearly, while the displacement of workers from manufacturing to services in advanced economies has coincided with a rise in labour income inequality, this increase was mainly driven by larger disparities in earnings across all sectors.

New policies are required to foster decent jobs for youth in an era of rapid technical change. The ILO (International Labour Organisation) estimates that 67 million young women and men are unemployed globally, and around 145 million young workers in emerging and developing countries live in extreme or moderate poverty. The ILO reminded that there were more than 700 million workers living in poverty in emerging and developing countries that were unable to lift themselves above the USD 3.10 per person daily threshold in 2017. The rate of progress has slowed, and many developing countries are failing to keep pace with the growing labour force. Despite significant progress, there were still more than 700 million workers in 2017 living in poverty in emerging and developing countries!!

Though the rebound in economic growth has strengthened job creation and the global unemployment rate is expected to fall slightly during 2017-19 (after a three-year rise), yet the labour market recovery is uneven across country groupings, with continued rises in the numbers of people unemployed in developing and emerging economies.

Meanwhile, the new automation and digital technologies pose further challenges. The opportunities they present will demand innovative policy solutions - proper infrastructure and equal access to information and technology should complement investment in education and skills and effective approaches towards lifelong learning.

Agreed - from a long-term economic perspective, the shift of capital and labour into different forms of economic activity is accepted as "structural transformation" with the natural consequence of changes in demand, technology, and tradability.

The IMF opines rightly that new evidence has been there on the role of manufacturing in the dynamics of output per worker and in the level and distribution of labour earnings. Such a shift in employment from manufacturing to services need not hinder economy-wide productivity growth and the prospects for developing economies to gain ground toward advanced-economy income levels.

The IMF urged policymakers to raise productivity towards supporting their goal of equitable growth, as the declining share of manufacturing jobs in overall employment has been a concern for policymakers and the broader public alike in both advanced economies and some developing economies.

Why not to hope that policymakers must ensure that workers in advanced, emerging and developing countries all benefit from a global trading system that produces fair outcomes. Let us take a positive view on these burning issues!!

Dr BK Mukhopadhyay, a Management Economist, is Principal, ICFAI University, Tripura, India.