The Finance Minister (henceforth FM) of the country has recently presented his budget proposals for the fiscal year 2021-22. This is the first budget prepared with more than a year's knowledge of the health and economic effects of COVID19 pandemic both in Bangladesh and the rest of the world. Predictably, it is a large deficit budget in line with the budgets of most other countries. Many of the broad details of the budget were already leaked out to the media perhaps to whet its enthusiasm or soften post budget reaction.

FM has proposed a budget with government expenditure set at Tk6.04 trillion and revenue at Tk3.92 trillion. The proposed expenditure is 6.28 per cent higher than that of the previous year, and the revenue is 1.8 per cent higher. FM had set the revenue for 2019-20 budget at 11.36 per cent higher than that of 2018-19. The expenditures in the earlier budgets were usually set at more than 15 per cent higher than that of the immediate past year. The unusually low rates of increase in revenue and expenditure envisaged in the proposed budget are perhaps a reflection of either the FM's grim expectations about the performance of the economy in 2021-22 or a necessary correction for the unattainable targets of the earlier years.

A very common question that is asked soon after FM has read out his budget proposal is whether the budget is 'realistic' or 'ambitious'. Since these terms do not lend to a single definition, it is useful to explicitly state what one means to avoid unnecessary argumentation. For the purpose of the discussion below let the realism and ambition of the budget be defined in terms of only implementation setting aside the important questions of pandemic response, allocations and appropriateness. This minimises talking at cross purposes.

If the government can demonstrate that the budget is within its capacity to implement fully, it seems reasonable to regard it realistic. The ability of a government to implement a budget depends on its capacity to do so. Since it cannot be observed, the only way we can infer the current capacity is by looking at how the government has implemented the budgets in the earlier years. An organisation as large as the government cannot dramatically increase capacity in a short time. It requires sustained investment in right efforts and activities, especially motivation and human capital formation, over a long period to build up capacity. With the lowest investment in human capital in the South Asia region Bangladesh government cannot expect to rapidly increase capacity such that the year-to-year variation on average will be small.

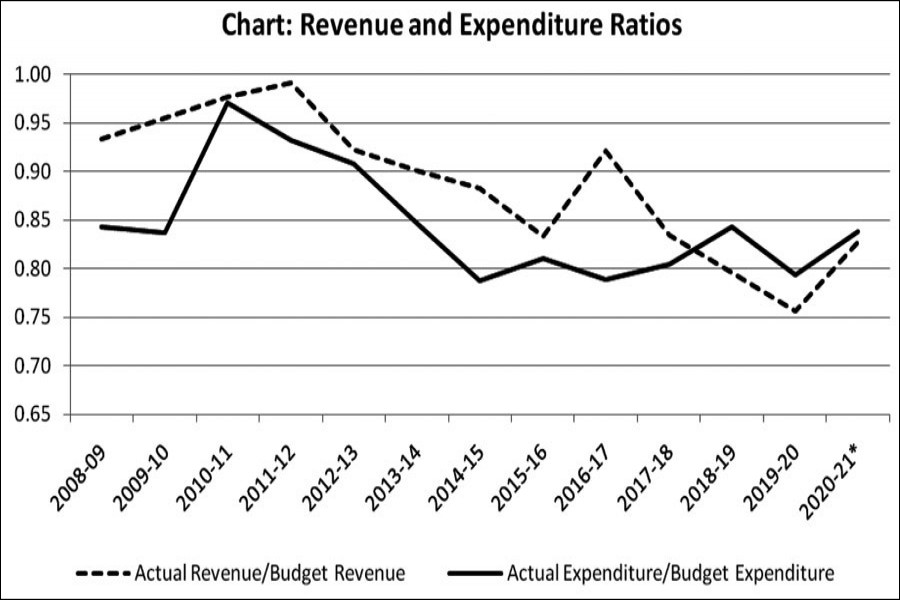

A visual representation of the actual rates of implementation of the expenditure and revenue targets set out in the budgets for the period FY2009 to FY 2020 is shown in the Chart. The dotted line shows the revenue realised by the government as a ratio of the original prediction or expectation of the revenue when the budget was passed by the parliament. The solid line is the ratio of actual expenditure reported by the Ministry of Finance in the fiscal reports and the expenditure originally stated in the budget. These ratios may be regarded as the indices of revealed capacity in respect of revenue collection and spending. A ratio less than one implies the government does not have adequate capacity to implement the budget fully.

The chart shows that the revenue ratio fell from a very high 97.7 per cent in FY2011 to a low of 75.6 per cent in FY2020 almost monotonically except for a spike in FY2017. The expenditure ratio on the other hand rose to 97.1 per cent in FY2011 and then fell off to 78.8 per cent in FY2015. Since then it has hovered around 80 per cent. There is little doubt that the budget performance has worsened since 2012-13. This could be due to either an unrealistic increase in the budget targets or a reduction in effort or both.

It is unlikely that the situation will improve much. The total revenue collection during the first nine months of the current year has been only 58.2 per cent of the budget target. At this rate the revenue ratio for the whole year will not be much better than that of the last year. On the other hand the government spent less than 40 per cent of the budget expenditure till March 2021. Although the government has a propensity to very considerably increase spending in the last months, the past trend suggests that the expenditure ratio may not be much above 80 per cent in the current fiscal. The lines in the chart clearly suggest that the government did not have the capacity to fully implement either the revenue or the expenditure budget especially since 2012-13.

Looking at the trend of the actual revenue collection and government spending over the past several years it seems that the implementation performance in respect of both the proposed revenue budget and the expenditure budget for 2021-22 will be about the same as the last few years. Consequently, by the criterion mentioned above it would be reasonable to conclude that the recent budgets were mostly not realistic. This is perhaps what most commentators have in mind when they question if the budgets are realistic.

The word ambitious normally has the connotation of aiming for something at the edge of, or beyond, the normal capacity. Since the 2021-22 budget is apparently not realistic because it is beyond the revealed capacity of the government to implement fully under reasonable assumptions, it could be said to be ambitious. Indeed, the repeated failures of the government during the past decades to implement the budgets fully have entrenched the view that the budgets are too ambitious.

Defining the implementation capacity in terms of the ratio of actual capacity and budget figures may seem very persuasive, but it may also make the issue rather flexible or even trivial. All that FM needs to do to ensure an excellent budget performance is to reduce the revenue and expenditure targets (ambition) of the budgets to actual capacities. This is perhaps what has been attempted in, or the pandemic has forced upon, the 2021-22 budget. For the first time in many years the expenditure and in particular the revenue targets show very small increases over the immediate past budget figures as mentioned at the beginning. Hence the likelihood of a better budget performance next year is better even without any extra effort. Lower ambition makes for greater realism.

A great many people are in awe at the size of the budget of six trillion taka. Nominal values are, however, not good indicators of real or relative values, and unsuitable for intertemporal or intercountry comparisons. The well-accepted practice is to use the ratio of the budget size and the GDP of the country for these purposes. The data provided in the budget speech show that 2021-22 budget is 17.47 per cent of the forecast GDP. This is less than the same ratio in the previous two years. FM has apparently reined in his ambition for the next year after poor budget performances over many years.

An important point worth noting is that the revenue and expenditure figures must be viewed in the proper context. The total expenditure shown in the budget is the sum total of the spending reported by all the ministries and offices of the government which receive and spend its funds. It is well known that the actual expenditure is greatly exaggerated. The scandals of government offices buying curtains for millions of taka each or pillows for tens of thousands taka and similar other stories have made headlines in the national dailies. Since such practices in procurements are almost routine, government expenditure is considerably overestimated.

On the other hand, business organisations and ordinary people pay a great deal more to the government functionaries than are shown in the government exchequer. The proverbial Titas or PDB bill collectors who have amassed great wealth obviously did so by under-billing the clients. A part of the payments the consumers made for receiving public services ended up in the pockets of these government functionaries instead of the accounts of the government. Many such payments are not reported and hence the actual revenue shown in the budget is essentially understated. This is particularly relevant in view of the frequent complaints that the tax-GDP ratio of the country is too low which leads to deficits even with relatively small budgets. These deficits could be reduced or turned into surpluses if corrupt practices that reduce revenue and blow up expenditure could be minimised. The impact on economic growth would be phenomenal.

The chart shows that the revenue ratio fell from a very high 97.7 per cent in FY2011 to a low of 75.6 per cent in FY2020 almost monotonically except for a spike in FY2017. The expenditure ratio on the other hand rose to 97.1 per cent in FY2011 and then fell off to 78.8 per cent in FY2015. Since then it has hovered around 80 per cent. There is little doubt that the budget performance has worsened since 2012-13. This could be due to either an unrealistic increase in the budget targets or a reduction in effort or both.

It is unlikely that the situation will improve much. The total revenue collection during the first nine months of the current year has been only 58.2 per cent of the budget target. At this rate the revenue ratio for the whole year will not be much better than that of the last year. On the other hand the government spent less than 40 per cent of the budget expenditure till March 2021. Although the government has a propensity to very considerably increase spending in the last months, the past trend suggests that the expenditure ratio may not be much above 80 per cent in the current fiscal. The lines in the chart clearly suggest that the government did not have the capacity to fully implement either the revenue or the expenditure budget especially since 2012-13.

Looking at the trend of the actual revenue collection and government spending over the past several years it seems that the implementation performance in respect of both the proposed revenue budget and the expenditure budget for 2021-22 will be about the same as the last few years. Consequently, by the criterion mentioned above it would be reasonable to conclude that the recent budgets were mostly not realistic. This is perhaps what most commentators have in mind when they question if the budgets are realistic.

The word ambitious normally has the connotation of aiming for something at the edge of, or beyond, the normal capacity. Since the 2021-22 budget is apparently not realistic because it is beyond the revealed capacity of the government to implement fully under reasonable assumptions, it could be said to be ambitious. Indeed, the repeated failures of the government during the past decades to implement the budgets fully have entrenched the view that the budgets are too ambitious.

Defining the implementation capacity in terms of the ratio of actual capacity and budget figures may seem very persuasive, but it may also make the issue rather flexible or even trivial. All that the FM needs to do to ensure an excellent budget performance is to reduce the revenue and expenditure targets (ambition) of the budgets to actual capacities. This is perhaps what has been attempted in, or the pandemic has forced upon, the 2021-22 budget. For the first time in many years the expenditure and in particular, the revenue targets show very small increases over the immediate past budget figures as mentioned at the beginning. Hence the likelihood of a better budget performance next year is better even without any extra effort. Lower ambition makes for greater realism.

A great many people are in awe at the size of the budget of six trillion taka. Nominal values are, however, not good indicators of real or relative values, and unsuitable for intertemporal or intercountry comparisons. The well-accepted practice is to use the ratio of the budget size and the GDP of the country for these purposes. The data provided in the budget speech show that 2021-22 budget is 17.47 per cent of the forecast GDP. This is less than the same ratio in the previous two years. FM has apparently reined in his ambition for the next year after poor budget performances over many years.

An important point worth noting is that the revenue and expenditure figures must be viewed in the proper context. The total expenditure shown in the budget is the sum total of the spending reported by all the ministries and offices of the government which receive and spend its funds. It is well known that the actual expenditure is greatly exaggerated. The scandals of government offices buying curtains for millions of taka each or pillows for tens of thousands taka and similar other stories have made headlines in the national dailies. Since such practices in procurements are almost routine, government expenditure is considerably overestimated.

On the other hand, business organisations and ordinary people pay a great deal more to the government functionaries than are shown in the government exchequer. The proverbial Titas or PDB bill collectors who have amassed great wealth obviously did so by under-billing the clients. A part of the payments the consumers made for receiving public services ended up in the pockets of these government functionaries instead of the accounts of the government. Many such payments are not reported and hence the actual revenue shown in the budget is essentially understated. This is particularly relevant in view of the frequent complaints that the tax-GDP ratio of the country is too low which leads to deficits even with relatively small budgets. These deficits could be reduced or turned into surpluses if corrupt practices that reduce revenue and blow up expenditure could be minimised. The impact on economic growth would be phenomenal.

The author is Professor of Economics, Independent University Bangladesh.