On March 1, 1971, I was watching an unofficial cricket test match between Pakistan and the touring MCC at Dhaka Stadium. Cricket matches were a lot of fun and I did not miss the opportunity to witness one if the game was played in Dhaka. Such matches were also an occasion to rail against Pakistani discrimination since no Bengali had ever made it to the first eleven in the Pakistan team. The one or two East Pakistanis that made it to the first eleven were not ethnic Bengalis; they were Urdu speaking East Pakistanis. This time around, my friend Roquibul Hasan, a fellow Bengali and a contemporary in Dhaka University was playing for Pakistan. He was only 19 and opened the batting. His bat had a triangular sticker with the words Joy Bangla and a Nouka (Boat), the election symbol of the Awami League. Roquibul later told us that there was quite a bit of commotion in the Pakistani dressing room as to why he had put a political sticker on his bat. The downside was that Roquibul did not bat well and scored only 1 in each innings.

On the last day of the match, the government announced that the national assembly session scheduled for March 3 was postponed till March 25. The stadium was full, everyone was supporting the home team, Pakistan, but in a moment the place exploded. People rushed into the ground and all the players except Roquibul were chased out. Bonfires were lit with chairs and the overhead canopies set alight. I trooped out with my companions and walked to Hotel Purbani, practically next door. Sheikh Mujib was holding a meeting inside. The crowd was growing bigger by the minute and nobody knew what was going on. Everyone expected Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to come out and speak but he never did. Some student leaders were speaking to the crowd over loudspeakers from the roof of the car porch when someone brought a Pakistani flag and set it on fire! The crowd cheered loudly. (We had gotten used to watching American students burn the American flag in protest of the Vietnam War.) Then, for the first time I saw the red, green and yellow flag of 'Bangladesh' being waved from the car porch roof. It felt strange. I felt pride but also fear.

Around dusk, an announcement came that Mujib had called a general strike on March 3. Government offices in the eastern province were instructed not to take orders from Islamabad. Military food suppliers were told not to supply anything to the cantonments and by and large most of them complied. The general strike was a complete success. Vehicles stayed off roads, shops and markets were closed, and educational institutions did not hold classes. Normal civic and economic activities came to a standstill. Subsequently, the strike was extended indefinitely and the word was that unless a definite date for the first session of the National Assembly was announced the strike would continue. It seemed as though the writ of the Pakistan Government had ended in East Pakistan. Everything including the functioning of government offices was being done on the instructions of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

From March 1 onwards, thousands would gather outside Mujib's house from the crack of dawn to late night to hear their leader but Sheikh did not make any statement. Instead, a public meeting was announced for March 7 in the racecourse maidan where he would speak. Everyone waited for the big event.

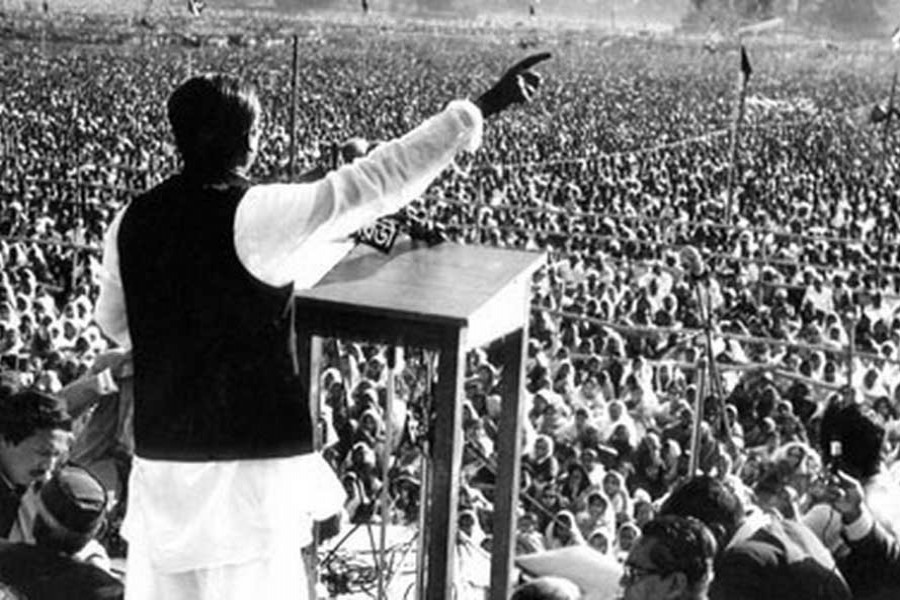

On March 7, people started converging on the racecourse from early morning. I reached there around midday. The place was packed as far as the eye could see. The crowd would eventually spill over to the adjoining roads and the adjacent Ramna Park. I had never seen such a mammoth crowd. We waited in the sun as military helicopters and light aircrafts flew overhead. Eventually, more than a million people would assemble there. People were speculating what Mujib would say. Would he live up to expectations? Would he declare independence and if he did so, what would the army do? Would they attack us from the air? Anything could happen. There was considerable nervousness but no one left the venue; such was the resolve and the nature of the defiance.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman arrived around three in the afternoon and the meeting got underway. Mujib did not make a prepared speech and was not looking at any papers; he spoke from his heart. It was an epoch making speech, it was fiery, defiant and yet he did not close the door for negotiations if that was still possible. He summed up the situation in the country and the feelings of the people of East Pakistan with a clear message to the Yahya government to follow democratic norms or the people of East Pakistan would do what they needed to do to establish their rights. He warned them not to use the military against the people and if any such attempt was made it would be resisted by the people by denying the army the food and water of Bengal. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's speech sounded like symphony to his audience. Although there was no outright declaration of independence, he did say: "The struggle this time is the struggle for our freedom! The struggle this time is the struggle for independence!" The speech was punctuated by thunderous cheers of Joy Bangla. It was his finest hour.

In the meeting, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman announced a complete non-cooperation movement against the Islamabad government. People were instructed not to pay taxes and he gave instructions for the essential services, banks, courts and government offices to function but only according to his instructions. From the following day, people of East Pakistan, irrespective of status, started following Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's directives. Newspapers carried reports and images of various preparations that were underway although most of it was only symbolic.

This piece is excerpted from A Qayyum Khan's book titled 'Bittersweet Victory: A Freedom Fighter's Tale'. (The University Press Limited, Dhaka, 2013)