The book 'Bangabandhu: Epitome of a Nation' contains a photograph of the cabinet formed under the stewardship of Sher-e-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Haq right after the historic victory in 1954 election of the team which contested under the banner of Jukto Front. There in the photograph we see a tall handsome young man standing next to the leader and looking proudly to the camera. How old was that young man at the time? He was only 34, hardly an age to face the reality of the cruel world so convincingly. Yet, he was doing exactly the same, as if by glaring straight into the destiny he was telling us not to keep our heads down even when time turns extremely unfavourable.

If you give a closer look, you might find in that group-photograph not only the reflection of that precise moment, which photographs usually reflect, but something beyond that. The young man was clearly displaying the signs of his future emergence as an undisputed and unparalleled leader that our country had given birth in centuries. We know 34 is an age considered to be a formative one in all senses and not an age to find a place very close to the top. But he did it at that young age, as if by getting a signal from his sixth sense that the time allocated to him was much shorter than that of many around him.

Merely a quarter of a century after the historic photograph was taken he was lying on the stairs of his sweet home with blood spilling around. No one was there to mourn his death and no one around to listen to what he had to say in that defining final moment when his soul parted from his bullet-ridden body. And he was only 55, much younger than many of us who are burdened with the guilt of doing nothing to salvage him from the barrage of diatribe thrown regularly at his direction almost for two decades since then.

The book also contains a somewhat blurred photograph of that tragic scene. I often wondered what made that photograph blurred and presumed that the photographer who was forced to take that image was in deep shock seeing the beloved leader's blood-stained body and his silent cry had the unwilling impact of shaking his hand while pressing the shutter. It's a pleasure to see that the slightly blurred but historic photograph has its rightful place in the wonderful book complied by Enayetullah Khan. This wonderful compilation can be termed one of our finest tributes to the country's finest leader that this land has ever produced.

In between the two photos, although the gap is of a relatively short period of just 25 years, things that happened in the life of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and in the lives of millions of us who had the opportunity of crossing the great river of destiny riding the same boat of time are of immense significance. And in most of those events, it was he who was at the centre of attention; sometime as a saint assuring us of victory even as we were on the verge of facing a great deluge, and most of the time urging us not to give up hope as he was shuttling between the iron fence of captivity and the warmth of his cozy sweet home where a family had always been kept in waiting for his much desired return. This painful process had paved the way for the emergence of a leader, who like Danko in Maxim Gorky's famous story, had ripped open his own chest to bring out his shining heart for showing us the way out of the dark forest and we followed him, not realising that once we are out in the light, Danko would fall to the ground after fulfilling the responsibility of salvaging his people. Isn't that what exactly happened to our leader? The book 'Bangabandhu: Epitome of a Nation' presents page after page enough evidence in text and photographs of this human tragedy centred on one individual who was born with endless love for his people.

In the time-span of a quarter of a century from the moment young Mujib is seen in the photograph standing proudly among the top leaders of his youthful days, he had travelled hundreds of thousands of miles to claim his rightful place in history as the sole leader of his people who would not waver from the simple desire of making them happy. And in return, he could win the trust of his people so convincingly that when he asked for their support, he received that without any question asked. The result of the elections held in December 1970 proves this beyond any doubt. What happened later was probably the expected outcome when a figure like him leads the nation so convincingly. However, that was also a source of envy that haunted him until the day he was gunned down so brutally. Those who envied him resorted to the age-old method of spreading fake news to taint the figure they had targeted. So are the stories of bank robbery and accumulation of wealth and undisclosed Swiss bank accounts. Every single of those charges turned out to be fake from the moment he was gone. So, Mujib was also the first victim in this country of the criminal act that we these days term "fake news". And the perpetrators remain unpunished till today.

The book tries to capture Mujib - the man of the people, as he walked day and night throughout the length and breadth of the friendly terrain of his motherland to make people aware of their rights. In between he also had to deal with other political figures of his time, many of whom were among those who descended from heaven, people who got indulged in politics by virtue of being born in the families of landed gentries or emerging merchant class. Mujib was the odd man out among that lot. He had neither the backing of an influential family, nor had the blessing of a leadership enjoying the honey-dipped cream of power. And by standing firmly on his own feet defying all the adversities, he could also break the age-old mould of leadership in our part of the world where leaders usually are those who are sent from the heaven and not those who mingle with people from everyday life.

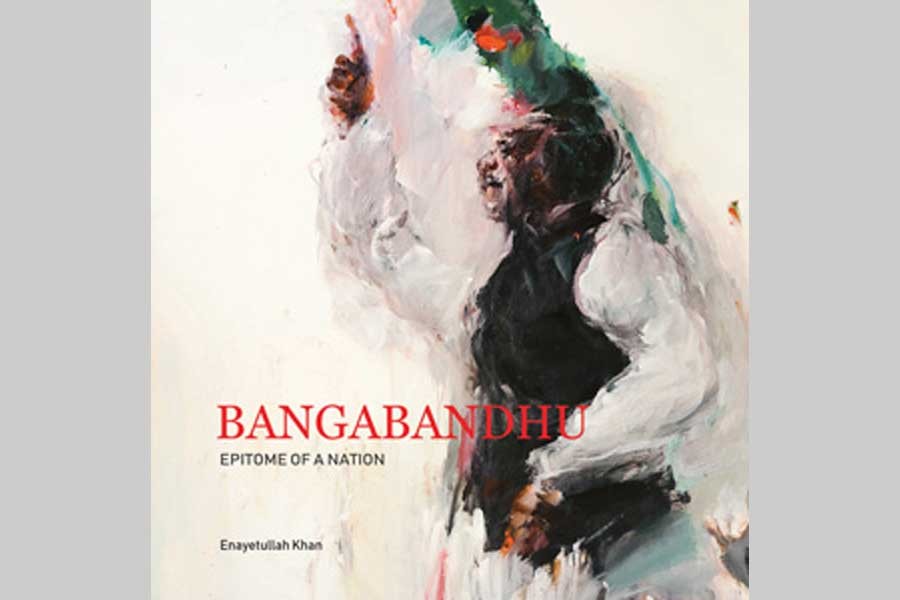

Enayetullah Khan has taken a timely initiative to present this genuine Mujib to a wider readership at home and abroad by publishing the book in English and enriching the text with photographs, and paintings of Shahabuddin. Mujib had the charm of winning very easily the trust of those who had the opportunity of encountering him face to face or even those who could look at the person from a distance. I have a friend at the Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan who belongs to those who had a chance encounter of him from a distance during an official assignment. RikioImajo has retired from the Associated Press after serving the agency for decades as a photographer. He was sent by AP to cover the OIC conference held in Lahore in 1974 and had taken a number of photographs of Mujib among other OIC leaders, including Yasser Arafat, HuarieBoumedine, Z. A. Bhutto and Muammar al Gaddafi. He once told me that the Mujib that he saw at the conference was a person made of a completely different mould. To Imajo Mujib looked more like a good uncle in the neighbourhood who is willing to extend his helping hand to whoever is in need. And it made him very sad when he came to know a year later what had happened to the person he saw as a good uncle of the neighbourhood.

This is the true face of Mujib, which is genuine to the core and without any colouring added for making it look beautiful. That same Mujib was also seen by the famous Japanese film director Nagisa Oshima, when he went to Bangladesh only a few months after the country was liberated. He was assigned to make a documentary on Mujib and was utterly surprised when he was led to the dining room of the leader where he was having breakfast with his family. The comment Oshima made in describing that scene is also a significant one that goes like this: he is probably the only leader in this world who enjoys such a humble breakfast in a humble surrounding. The book obviously did not fail also to present that Mujib to the readership and here it differs from many others.

A chapter on Col. Jamil, the only fallen hero who responded to the leader's call and sacrificed his own life in the failed attempt to save Mujib, adds further significance to the book. Late Jamil's brave act shows clearly that Mujib was not abandoned by all at that crucial moment, like those, who still tend to taint his image, would like to tell us.

Monzurul Huq is a Tokyo-based Bangladeshi journalist. He also teaches at Japanese universities.