The ready-made garment (RMG) industry has been Bangladesh's key export industry and one of the main job-creating sectors for the last three decades. Minimum wage for RMG workers is Tk 5,300, which was set by the government in December 2013. However, there is widespread concern among the workers about minimum wage not meeting their basic needs, and not allowing them the ease, comfort, and decency of leading a respected and dignified life. An ILO (International Labour Organisation) study showed in 2015 that, among the top 20 RMG-exporting middle and low-income countries, Bangladesh was among the countries with the lowest wage for unskilled labour.

In recent time, there is also a growing demand for moving towards a living wage in the RMG sector in major RMG-exporting countries. The definition of living wage incorporates the idea that workers and their families should be able to afford a basic but decent life style that is considered acceptable by society at its current level of economic development. Elements of a decent standard of living include food, water, housing, education, healthcare, transport, clothing, and other essential needs, including provisions for unexpected events.

There are notable differences between living wage and minimum wage (Table-1). The scope of living wage goes beyond subsistence living, incorporating a larger array of amenities far beyond subsistence living. On the other hand, minimum wage is set within the requirements of subsistence living only. Minimum wage is regulated by law, while living wage is yet to fall within such regulatory framework. Another key aspect is that living wage is set within the parameters of negotiation between the industry-owners and their workers. Living wage is rather a consensus and understanding-based wage equilibrium. The focus of the minimum wage is about setting the lowest remuneration, while the focus of the living wage is to move toward a decent livelihood. While the minimum wage is the outcome or result of the union organisation working together to ensure a bare minimum, the living wage arose in the socio-economic scene as a reaction to neo-liberalism, Reaganism, and Thatcherism. The obvious downside of imposing minimum wage or living wage is that the wage would rise above the equilibrium, thus leading to unemployment; whereas the argument in favor of minimum wage or living wage is that these are Keynesian and post-Keynesian in nature, relating to stimulating demand for improving the state of the economy.

The Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) has developed a definition and methodology that operationalised a minimum living wage. The AFWA research estimates a minimum living wage floor across the RMG industry in Asia, and is evidently one of the first efforts to establish an industry-wide living wage across national borders. The standardised floor wage is not about setting the same wage in US$ terms, considering variable exchange rates, the diversity of currencies and standards of living across Asian economies. Rather, a common formula has been devised based on consumption needs. The Asia Floor Wage is calculated in PPP$ (Purchasing Power Parity US$), which is an imaginary currency built on the consumption of goods and services by people, allowing standard of living among countries to be compared regardless of the national currency.

The estimation of living wage for Bangladesh, as per the Asia Floor Wage in terms of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), was Tk 25,687 in 2013, Tk 29,422 in 2015, and Tk 37,661 in 2017. While such figures are obtained by calculations based on PPP, these figures may not realistically match with the current status quo of the minimum wage conversation about Bangladesh. That is why these figures ought to be interpreted very generously as if these are the most ideal scenario that the RMG industry of Bangladesh needs to achieve.

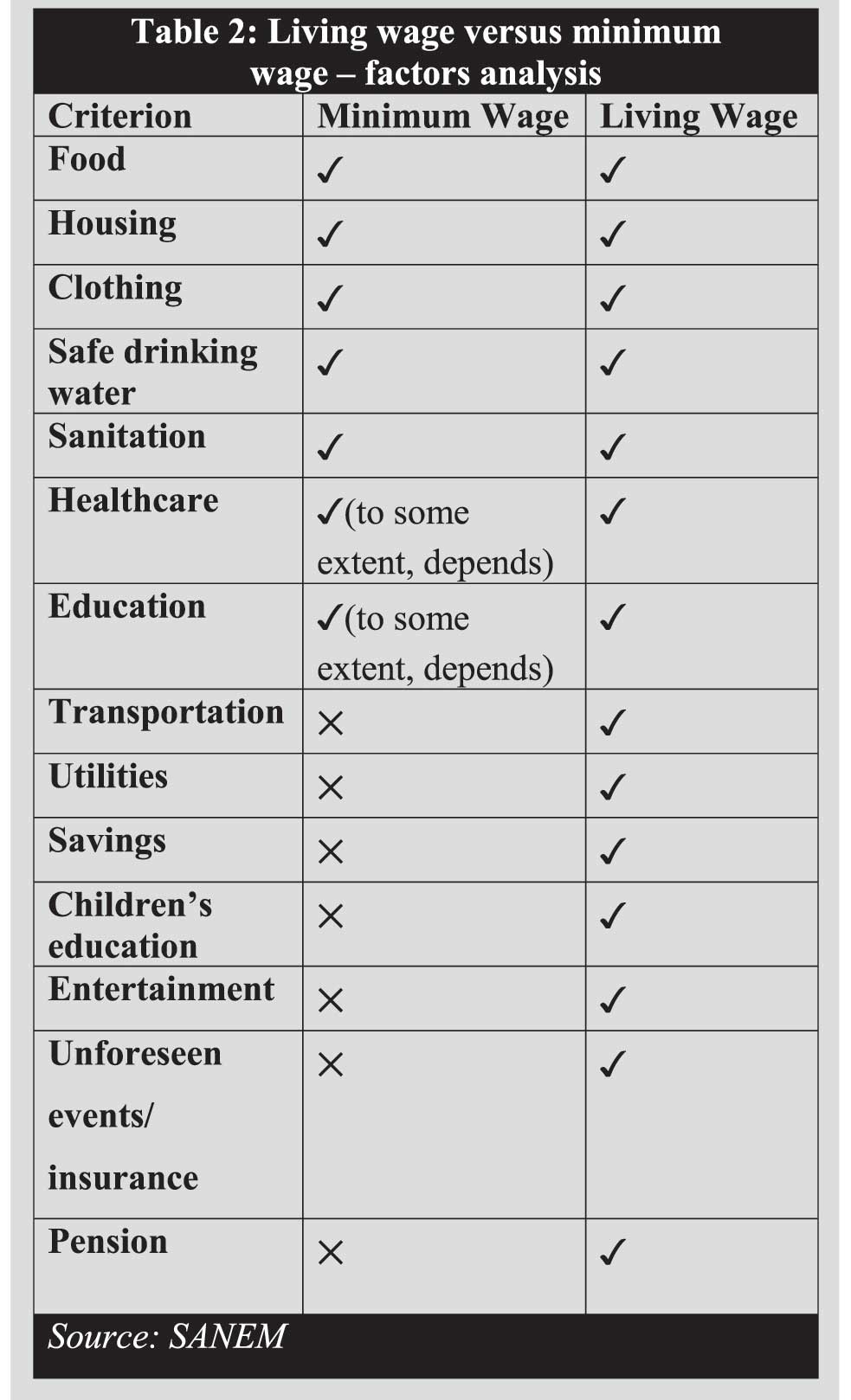

As shown in Table-2, there are significant differences while considering factors for analysing minimum wage and living wage in the context of Bangladesh. While both definitions of wages take into account food, housing, clothing, safe drinking water, sanitation, and to some extent healthcare and education, living wage would allow workers to take care of costs regarding transportation, utilities, savings, children's education, entertainment and unforeseen events.

If a country considers upgrading its path towards living wage, it might take into account the combination of upgrading minimum wage policies reflecting more of the living wage factors alongside robust economic policies, comprising public-private sector cooperation. The multi-sectoral approach, outlined below, ought to work seamlessly to further the goal of moving towards living wage in Bangladesh.

First, the implementation scope of minimum wage should be expanded considering the number of dependent family members, updated need of food, housing, healthcare, and children's education.

Second, the idea of the pension scheme needs to be included when determining the living wage for the RMG industry of Bangladesh. Due to the high mobility of garment workers from one factory to another, many workers remain outside the scope of pension funds.

Third, the government can design a healthcare scheme attuned to the needs of the RMG workers. This healthcare service can employ private-public partnership, including health insurance, employee health funds, and savings scheme to address emergency health needs.

Fourth, the RMG industry should identify which small investors may face difficult consequences due to the introduction of living wage. To help those businesses, a time-bound support scheme can be devised for these small industries, helping them cope with the new wage laws. Also, the support structure can incorporate incentive pool comprising tax breaks, low interest loans and less regulatory requirements for the struggling small industries.

Fifth, improving workers' skill and productivity is important for implementing living wage. Improving workers' skills through training will contribute to transit to production of high-end product. Such initiatives will help the RMG sector to increase its export earnings and improve the sector-wide profit bottom line, thus improving the sectoral wage overall.

Sixth, providing non-monetary benefits like rations, housing facility, and education may prove to be cost-effective in the long run. Such non-monetary benefits will reduce the burden on wage negotiation and may prove to be a faster scalable solution than relying on only wage to take care of all the needs.

Seventh, negotiations with buyers and brands are also considered very important as buyers are key players in the RMG sector. If the buyers recognise the cost of labour within the framework of living wage, then the negotiation between buyers and sellers relating to living wage would possibly be more cooperative and fruitful for agreeing on a fair and just living wage.

Therefore, moving from 'minimum wage' to 'living wage' in the RMG sector requires a major change in the policy discourse, and it is clearly a challenging task for Bangladesh as well as other countries. Moving to the living wage also requires improvement in the business environment of the country; especially coordination between sectors is paramount as it involves a multi-party dialogue, cooperation, and improvement in business environment. In that regard, the path towards a living wage by respecting the workers' basic livelihood demands and considering the competitiveness of business environment underscores an evolving and improving process, projected towards equality, fairness, and competitiveness.

Dr. Selim Raihan is Professor of Economics, Dhaka University, and Executive Directors, SANEM. Email: selim.raihan@gmail.co; Marjuk Ahmad, Learning Experience Designer, Bangladesh Youth Leadership Center, Email: dreamexpress2021@gmail.com; Dr. Farazi Binti Ferdous, National Consultant,

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Email: bintiferdous@gmail.com