Two years have passed since extreme rains and flash floods inundated this fertile rice-growing region in northeastern Bangladesh, but farmer Shites Das still sees the lasting impact today: his neighbours are abandoning their homes and fields.

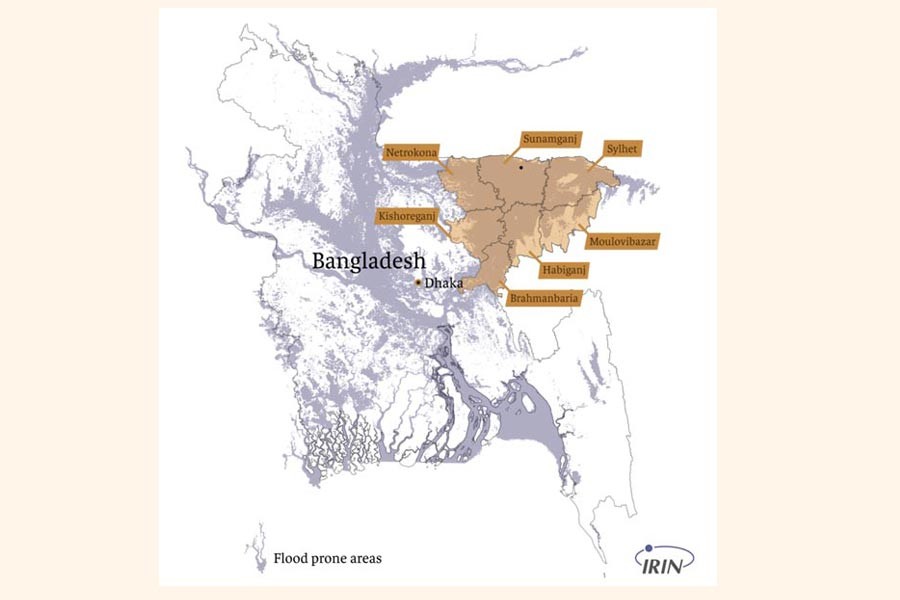

In March 2017, torrential rains burst river banks, washed away roads, and damaged 220,000 hectares of precious rice crops - weeks before the yearly monsoon rains typically set in. It was the start of the worst flooding to hit the country in years. Rice imports skyrocketed to cover a national shortfall, more than 80,000 homes were destroyed across Bangladesh, and in tiny Daiyya village, many families were left without food or crops to sell through the year.

"In my 32 years, I've never seen such hunger," Das said.

Families here say such extremes have become increasingly common: warmer winters, drier summers, and more erratic rains that leave farmers guessing.

"We have no fertility of land like in the past," Das said. "This has happened because of climate change."

Climate scientists typically speak in general terms when explaining the links between climate change and extreme weather - global temperature rise makes volatile weather more likely and more severe.

However, there's a growing body of research zeroing in on climate change as the likely culprit for specific disasters that spark humanitarian emergencies - including the flash floods that submerged Daiyya village.

In December, climate scientists published new research that for the first time examined the link between climate change and Bangladesh's pre-monsoon rains. University of Oxford researchers analysed data showing that six-day rainfall totals over March and April 2017 exceeded flood thresholds by more than a third. Using historical data and model simulations, the researchers concluded that human-induced climate change "doubled the likelihood of extreme pre-monsoon rainfall" during that time frame.

This "extreme event attribution" research was one of 17 similar papers published by the American Meteorological Society last year. Other studies found the marks of climate change in disasters from floods in Peru to heatwaves in Europe and China.

In Bangladesh, one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change, it's further evidence of what many here already know: weather extremes are having life-altering impacts.

World Bank research predicts climate change could force tens of millions of people to migrate within their own countries by 2050, including some 13 million in densely populated Bangladesh alone.

The depleted villages of Bangladesh's northeast offer a real-time glimpse of how dire climate displacement warnings are becoming a reality: village by village; family by family.

Facing year-on-year crop loss and unpredictable weather, households here have been moving to the cities in droves - giving up on the rice farming that has sustained them for generations. Das estimates nearly one third of his village has left for good.

Households here have been moving to the cities in droves - giving up on the rice farming that has sustained them for generations.

"Those who left our village in 2017 have not come back," he said. "People got scared."

THE NEXT LOST CROP

Bangladesh's northeast is a land of stark contrast, where water is plentiful during the monsoon season, and drought-like weather prevails in the dry season.

It's dotted with haors - seasonal wetlands where boro, a type of paddy rice, is harvested as the monsoon season begins, typically in April and May. The region is one of the country's rice bowls, contributing more than 16 per cent of boro rice production each year.

But it's also one of Bangladesh's poorest areas; the UN says more than a quarter of its 2.5 million population live in poverty. People mainly scratch out a living through fishing and duck farming, and by cultivating boro rice, which is only harvested once a year.

Villages here were unprepared for 2017's sudden floods.

Das said he watched as farmer after farmer lost their entire crop. His own crop was wiped out; he survived in part by selling his valuable cattle at half the market price, he said.

Others weren't as lucky. In nearby Vatidhar village, 60-year-old Anu Begum said she relied on humanitarian food aid to survive.

"We managed a meal, skipped another," she said. "It was year-round suffering."

Humanitarian group BRAC, which started life in this district, stepped in with more than $2 million in food and cash aid that kept some families going for a year after the floods. But it covered only a fraction of the needs, said Parul Akter, who coordinates the NGO's programmes in the area.

"Our support was a drop in the ocean," she said. "Every household suffered."

People in Vatidhar estimate that half of the village's roughly 700 people have migrated to the cities since the floods.

While there are no official statistics tracking the area's migration after the floods, Akter said one third of BRAC's 18,000 microfinance borrowers from one sub-district alone deserted their villages to find jobs in the eastern city of Sylhet, the southern port of Chittagong, or the capital, Dhaka.

"People are worried about the next crop loss," said Ali Hossain, a former local government representative in the area. "Even big farmers having up to 60 acres of land have quit farming."

The steady drain of farmers from one of Bangladesh's main rice-producing regions could also have wider implications for food security. In 2017, rice imports soared to more than three million tonnes from less than 100,000 tonnes the year before - in large part due to shortfalls caused by the floods. At the same time, domestic rice prices climbed 30 percent - beyond the reach of the most vulnerable.

Anwar Faruque, a former agriculture secretary who now consults for international development organisations, said a loss of haor rice crops could spark a food "crisis" for the entire country. This could lead to even more substantial imports and hiked prices.

"The ultra-poor will be affected," he said.

A SIGN OF THINGS TO COME

The northeast's village-level population shifts were set in motion by a disaster, which in turn was likely triggered by climate change.

The 2017 floods are the "early beginning of the trend" reflected across the country, said Atiq Rahman, a climate scientist who co-authored a chapter on vulnerabilities in the 2007 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - the UN body that assesses climate science.

And estimates suggest 300,000 to 400,000 new migrants each year head to cities in Bangladesh, driven by a complex mix of economic and environmental pressures.

Experts warn that Bangladesh must boost preparations to help citizens adapt to climate change and better manage migration: development projects that help rural families weather the storms and offer a reason to stay home, for example.

"If your homestead is high, if you've adequate food, you can minimise your losses," said Rahman, who believes that current government efforts are inadequate.

AKM Nuruzzaman, a village official, said that internal migration is a necessity for many rural families in Bangladesh. Even when the monsoon rains come as scheduled and harvests are bountiful, there are no major industries and few job opportunities when it's not farming season in his sub-district, he said.

Many households rely on a migrating family member to send money back to the village. Others need more help to diversify their crops and income, he said.

ADAPTING

Some efforts are already underway.

The country has ploughed more than $400 million into its Climate Change Trust, a state-funded body that finances adaptation and mitigation projects by government agencies. Roughly 80 percent of these funds have gone toward helping Bangladeshis adapt, said Mokhlesar Rahman Sarker, the fund's deputy head.

However, none of these adaptation projects cover the northeast haor region - in part because there has been little research about climate change's impacts here, said AKM Mamunur Rashid, a climate change specialist with the UN Development Programme.

But regular government departments are building projects such as submersible roads, which are designed to withstand floods, connecting villages to local markets even during the monsoon season.

Other aid projects are helping local families adapt: a district-wide UN-funded programme has built protective walls to fortify villages against floods, and BRAC has introduced new varieties of rice that can be grown and harvested faster.

But these efforts will come too late for those who have already left.

A few months after the 2017 floods ravaged her family's rice crop, Niyoti Rani Das, 51, took her two children and left Daiyya village for a city near Dhaka.

Her eldest daughter abandoned her studies to help support the family. Together, they earn about $160 each month working in the booming but perilous textiles industry. Half the salary is eaten up by rent, and the family can't afford school fees for the youngest, a 12-year-old boy.

Das and her children live in a slum by a railway line and scramble to make ends meet. But she won't return to her village: she has a sliver of land, but no rice to grow, she said.

The piece was originally published by IRIN.