David Lewis is a Professor of Social Policy and Development, Department of Social Policy, London School of Economics (LSE). He has devoted an important part of his life so far to doing research on Bangladesh's development. David has long been an ardent admirer of Bangladesh. It is reflected by the sheer number of researches on Bangladesh's development that he has so far carried out.

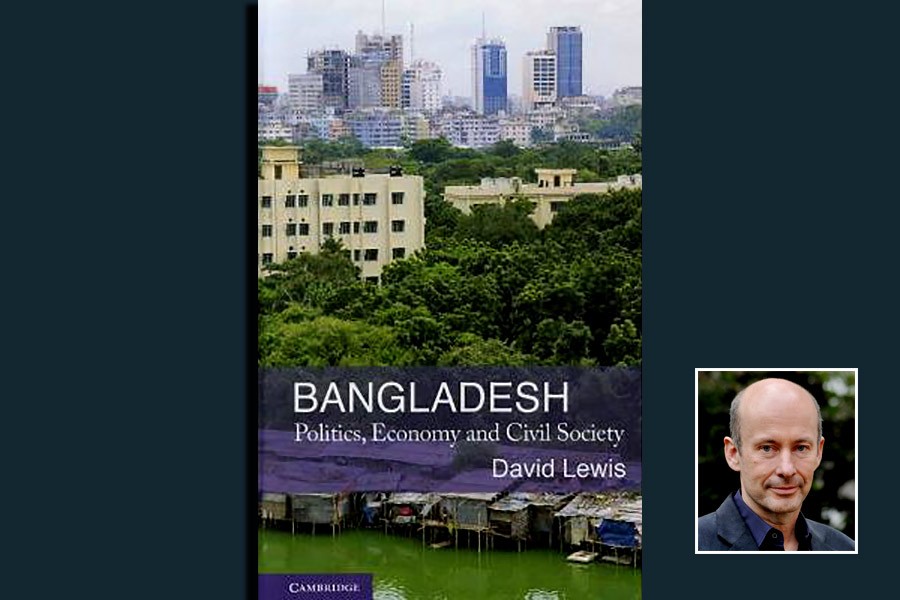

His Ph.D thesis titled 'Technologies and Transactions: A Study of the Interactions between New Technology and Agrarian Structure in Bangladesh' was published by Dhaka University in 1991. His seminal book, 'Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society', was published by the Cambridge University Press in 2011. It documents Bangladesh's struggle for independence from Pakistan and its emergence as a fragile, but functioning, parliamentary democracy. It examines the economic, political and social changes that have taken place in the country over the years. Lewis argues that Bangladesh is now becoming of increasing interest to the international community as a portal into some of the key issues of our age - such as development and poverty reduction, climate change adaptation, and the role of civil society and state in promoting democracy and stability in Muslim-majority countries. Despite its difficult past and many continuing challenges, the country is making remarkable progress. In this way the book offers an important corrective to the view of Bangladesh as a 'failed state'.

David Lewis also led a co-authored book in 2017 (with Abul Hossain) titled 'Revisiting the Local Power Structure in Bangladesh: Economic Gain, Political Pain?'. The research is based on repeat visits, within a span of time, in selected areas of Bangladesh (greater Faridpur). In the earlier study, the authors presented picture of a slowly changing local power structure in greater Faridpur. New institutional spaces were opening up to enable the poor to uplift themselves, the evolving inclusivity of some local institutions etc. The new study documents both continuity and change in rural areas as far as power structure is concerned.

"Economic dynamism has intensified since the mid-2000s, resulting in improved livelihoods for many people. Women's market participation has increased as many continue to access new economic opportunities (often with support of NGOs). Communities are more geographically and socially connected than before, and households have greater choice in the range and type connections they seek to form. Local, national, and transnational communications and migration opportunities have increased. Progress in achieving women's political inclusion into local institutions is occurring, albeit at a slow rate. Elements of an older power structure remain, with the persistence of patron-client relations, elite clan politics, and patriarchal norms, but these are slowly changing. The range of patrons people can access has continued to widen, increasing opportunities for those with less power to pursue more favourable forms of connection. Within power structure, the blurring of formal and informal roles and relationships has continued, creating a complex 'web' of relationships that both limits participation and civic engagement but nevertheless offers up some opportunities for incremental inclusive change".

What is different today? - posits a million dollar question. Civil society space has been reduced, particularly that was formerly occupied by radical non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society groups addressing rights-based development in relation to land, local political participation and civic engagement. "As a result, there are fewer opportunities for the types of win-win coalition we have identified and predicted would become more frequent in the earlier study….While there is a wider range of patron available, opportunities for poorer people to build horizontal forms of solidarity remain limited…..Local level political competition has also diminished as the ruling political party has consolidated its control of local power structure and weakened any formal political opposition… The forms of political competitor that do take place are now primarily expressed through increasing factionalism at local level within the ruling party…The combination of stronger local livelihoods and reduced democratic space is producing mixed outcomes for poor men and women…But the overall picture of economic gain has not come without a cost, which takes the form of political pain… Economic gain may currently be taking place with levels of political pain that has not been particularly severe, but these could become more acute in the future if these problems are not fully addressed".

In his most recent visit to Bangladesh, David Lewis spoke on 'Policy Process and Sustainability" at a seminar. It was intermittently intervened with 'provocative' propositions with a view to thinking policy better than we now do. Moderated by Faruque Ahmed, Executive Director, BRAC International, the seminar was mainly meant for BRAC Leadership. He kicked off the discussion with three a priori hypotheses: policy process is not linear, policy makers don't exist and the widening gap between policy and implementation.

Who are policy makers? In common parleys, they appear to be a bunch of different stakeholders including bureaucrats, politicians but could also include frontline field workers in a regime of bottom-up planning. It should, however, be remembered that, all policies are social policies as far as policies target the population. There seems to be a general conclusion that policy process is not linear.

Abdul Bayes is a former Professor of Economics at Jahangirnagar University.