Khokon Chowdhury began his clothing business a decade back, and his business had been growing since with daily sales of around Tk 15,000 until an upset came down.

Mr Chowdhury, 43, opened his small business at Olonker Crossing in Chattogram and would sell almost all types of female clothing together with his three employees. He took his largest loan, worth Tk 500,000 ($5882), from a local informal moneylender, Ghasful, in March 2020 to invest more in his growing trade. It went disastrously wrong from there. His shop closed when all closed under a national lockdown later in March 2020 amid corona onslaughts.

An attempt to revive his business was cut short when Bangladesh was hit with a second devastating wave of the global coronavirus pandemic in March 2021. In a further stroke of misfortune, he caught Covid-19 in April 2021 along with his two staff members.

The clothing shop is now open -- with its colourful signboard now dusty and dented. Chowdhury is no longer able to repay his loan as his sales dropped to one-third of the pre-pandemic level.

"It's an act of God. Actually, it's out of my hand," he says, as he rues the sudden change of his fortune.

Chowdhury is one of the millions of micro- cottage-and small-business owners in Bangladesh struggling to pay back debts and recover from the pandemic consequences.

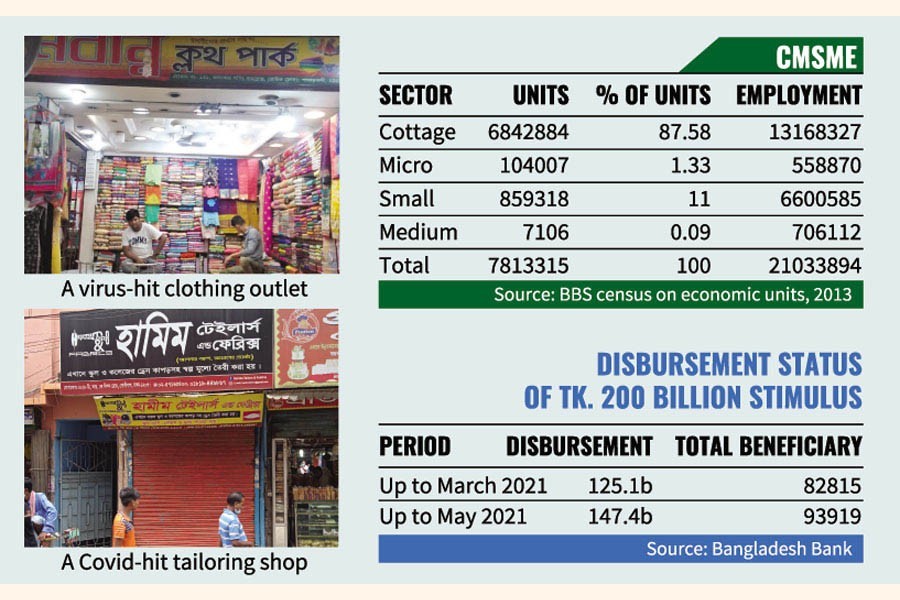

The group of small businesses, who invest between less than Tk 1.0 million and Tk 7.5 million, is believed to be one of the country's biggest economic pillars in terms of employment. Bangladesh's expansion of the CMS in recent decades has strengthened following rise in per-capita income of people, reaching US$2227, more than double the 2012-13 status. The economy also expanded threefold to Tk 30.1 trillion from the Tk 10.1-trillion mark in eight years.

A survey conducted by UN Capital Development Fund found over 2.0 million merchant retailers in Bangladesh. They together transact more than $18.42 billion annually (2018). This is a small fraction of more than 7.8 million CMS enterprises.

The small businesses have little access to the formal lending system leveraged by collateral. They, however, borrow from expensive sources to meet their urgent cash needs, making it one of the healthiest pockets for their funding. It is estimated that such micro-financiers lend to around 80 per cent of small businesses. They pay 24-percent interest -- 15 percentage points higher than rates in the banking system -- to the informal lenders.

The micro-financing, pioneered by Nobel-winning Grameen Bank, usually provides collateral-free loans, unlike the formal banking channel. The credit cap, not exceeding Tk 500,000, has a repayment period of 12 months. The repayment rate with such institutions for small businesses was almost cent per cent during the pre-covid period. The pandemic has forced down the rate to 60 per cent during the first wave in 2020. But it now ranges between 80 and 90 per cent, according to MRA or Microfinance Regulatory Authority.

The pandemic has also upended the dynamics on other economic fronts, with worldwide widespread disruptions to production, supply chain, communications et al.

The economy suffered a historic contraction by 3.5 per cent in the year 2020. The MFIs' funds shrank by at least Tk 200 billion due to the pandemic.

For the lack of formal cheap funding and adequate safety net, meanwhile, the small businesses have been brutally exposed as they have been struggling to operate business for lack of finances needed to meet some urgent expenditure during this pandemic: staff payment, shop-rent and injecting new investment.

The formal financial institutions, who procure cheap money through deposit taking, lend to corporate entities plagued by one of the world's highest bad-loan ratios. They usually do not fund small enterprises. The biggies, by contrast, indulged in large-scale corporate scams including Hallmark, Bismillah Group and many others and were accused of siphoning off money.

However, to avoid mass layoffs and closures, the government announced stimulus packages worth Tk 1.4 trillion-approximately 5.0 per cent of Bangladesh's GDP. Some Tk 200 billion has been allocated for the CMSMEs since the package was announced in April 2020.

But this large but underserved manufacturing and the trading group was also largely left out of the packages despite the government's repeated move to include them. The disbursement from the package is around 72 per cent in 16 months.

Analysts say banks remain reluctant to fund such vulnerable demographics which they treat as 'unsecured' and 'risky' sector.

Dr M. Masrur Reaz, chairman at the Policy Exchange of Bangladesh, who studied the small businesses during this pandemic, told the FE almost all cottage, micro and small businesses are in the informal sector. By virtue of being informal, the majority of them do not participate in the formal banking sector.

"The interest-rate cap (9.0 per cent) also discourages the bankers from making an extra effort to locate qualified CMS [cottage, micro and small] firms and extend loans."

Actually, loan-servicing cost for the small firms [having investment around Tk 1.0 million for micro and cottage and Tk 7.5 million for small manufacturers] is above 9.0 per cent in Bangladesh, says the economist, who earlier worked at the private-sector arm of the World Bank, IFC.

Dr Masrur noted when the stimulus came in (disbursed almost entirely through banking channels and based on prior banking relationships), neither were these CMS on the list available to the bankers/government nor were the bankers able to extend loans to them as they lack banking tracking record.

"The big corporate and clothing manufacturers have eaten up all the packages," says Dr. Ahsan H. Mansur, executive director at the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI), a local think tank.

The big corporates have been tapping easy liquidity from the formal finances and availed of stimulus funds, too.

"To my mind, there could be a shift in market share -- strong becoming stronger, weak becoming weaker," Dr Mansur said.

He fears this type of funding from the MFIs could leave scars on them, weighing on growth and exacerbating inequality for years to come.

Dr Zahid Hussain, former lead economist at the World Bank, told the FE that the banking model and microfinance model are two different models. Under the banking model, where the interest cap is 9.0 per cent, the banks cannot reach the small enterprises.

To ensure access to the stimulus package, he said, financial infrastructure is there: Sonali Bank and other state-owned banks, BSCIC [Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation], PKSF and its 200-plus partner organisations.

He says the infrastructure has a lacking in good governance and simply for this reason they could not reach the small businesses.

Prof Dr Selim Raihan, executive director at SANEM [South Asian Network on Economic Modeling], told the FE that there were bribery practices for taking loans by the CMS.

The SANEM has conducted five surveys since July in 2020 on the covid impacts on business. Dr Raihan said to reach out to the small businesses the conventional approach will not work. "We need new and innovative approach to reach the small businesses."

He noted that there are many best practices in the world on how to reach small businesses. "We should now explore that practice otherwise we cannot reach out to them."

Bankers argue that they prefer lending to those sectors where returns are safe.

Syed Mahbubur Rahman, the managing director and CEO at Mutual Trust Bank (MTB), said: "Banks prefer investing big chunk as it involves cost. Costing for sanctioning Tk 10 million and Tk 1.0 million is almost same. So banks avoid small loans."

Banks need some documentation which they lack, he told the FE.

When the disbursement for CMSME remained poor, the government allocated Tk 5.0 billion for PKSF [Palli Karmasahayak Foundation], an apex body of micro-lenders. PKSF disbursed through its member MFIs Tk 2.5 billion or half of its allocation at a rate of 18 per cent.

But, Dr Zahid Hussain said the fund is very inadequate considering the needs of the CMS entities. He also finds a need for strengthening supervision as to whether the MFIs are charging higher interest or not on the stimulus funds.

Md. Yakub Hossain, a director at the Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA), said they have been monitoring the situation.

"My number went viral. So I will take action if any higher interest is charged."