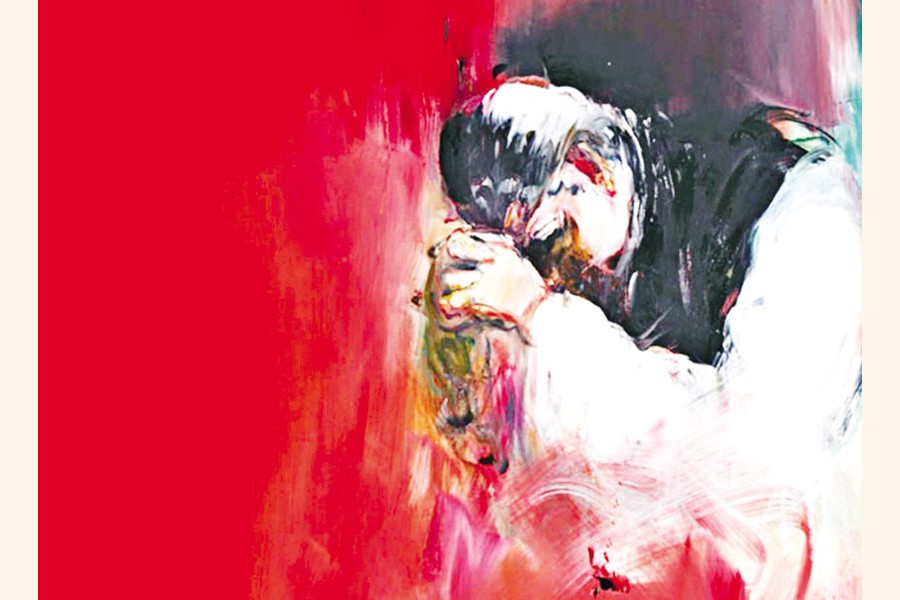

It was the end of a beautiful dream for all of us in this land.

Decades after his sudden, violent passing, with the ravaging ramifications of the coronavirus pandemic yet raging all over the world, we do not hold ourselves back from recalling the Colossus who reshaped our identity as a people.

And we do that through remembering the tragedy that rises in our collective soul this morning, for on this day 47 years ago, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Father of the Nation, was assassinated along with most of his family through the working of a vast, sinister conspiracy shaped at home and abroad.

Bangabandhu was only 55 when his life was rudely put to an end. But the dreams that he caused to flower in our hearts, the aspirations he inspired in our thoughts, the self-esteem he engendered in our consciousness were not to be murdered.

How do we remember that macabre day when Bangladesh was laid low by the monstrosity of the villainous men who seized the state and took all of us hostage?

Moments after the soldiers completed their satanic mission in the pre-dawn hours of August 15, 1975, it was given out on the radio that Bangladesh had been declared an Islamic republic. That, of course, was not true, as later events were to prove. But that the country had been forced at gunpoint to take a regressive step towards what would amount to communalism was made clear through the invocations to religion made by the assassins.

One of the more eerie aspects of the bloody coup was the patent glee with which Pakistan welcomed the fall of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his government. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto cheered the rise of an 'Islamic' Bangladesh and announced a dole of rice and cloth for the Bengalis. And then came the radio and television address by Khondokar Moshtaq Ahmed, the commerce minister who had suddenly and improbably turned into 'president'. Broad overtones of rightwing religious politics underlined his remarks.

Bangladesh had taken a wholesale journey back to darkness. The four brilliant men behind the 1971 Mujibnagar government were murdered in the putative security of prison barely three months later. But if that was the beginning of a rejection of history as it had shaped up in 1971, there was worse to come. The infamous indemnity ordinance was but a stepping stone to the insidious things that were yet to be. And yet hope of a sort dawned, feebly, when Khaled Musharraf put the killers out to pasture through his coup of 3 November 1975. Four days later, he was dead.

All-enveloping darkness threatened to consume secular values in the land.

With the Zia regime firmly ensconced in power, larger plans were being made to strip the country bare of the basic decency it had historically symbolised. M G Tawab, heading the air force and operating as a deputy martial law administrator, organised a 'seerat' conference that left few in any doubt about the military junta's intentions. In February 1976, matters became a little clearer when Khondokar Abdul Hamid, a journalist and Zia acolyte, spoke of 'Bangladeshi nationalism', a mishmash of ideas intended to drill holes in the Bengali nationalism that had propelled the nation to war against Pakistan in 1971.

Then came Zia's unilateral act of tampering with the constitution. Secularism, socialism and nationalism were prised out of it and replaced with themes that were a clear negation of Bengali history.

The parliament elected in February 1979, stacked as it was with apologists for 'Bangladeshi nationalism', adopted the fifth amendment to the constitution. Included in it was the indemnity ordinance. Bangabandhu's killers were safe, for no court could bring their misdeeds into question. Many of them were sent off abroad, to serve as diplomats at various Bangladesh missions!

A definitive manifestation of the distortion of history came through the reluctance of the regime to identify the Pakistan army as the perpetrators of the genocide in 1971. On Independence Day and Victory Day, the reference was only to an 'occupation army', never to Pakistan's soldiers. Through a repeal of the Collaborators' Act of 1972, the door was opened for ageing supporters of Pakistan's genocide to re-enter politics in independent Bangladesh.

Under the cover of 'Bangladeshi nationalism', the Jamaat-e-Islami, Muslim League and other Pakistan-friendly parties swiftly occupied the political arena. On state-controlled radio and television, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman turned into a non-person, a fact that persisted for as long as General Zia held on to power. Absolutely no mention of the Mujibnagar government was there; and sanitised versions of national history made their way into school textbooks.

Ziaur Rahman's murder in May 1981 only speeded up the process of historical distortion. General H M Ershad, the nation's second military ruler, pushed the country even more into a communal corner when he decreed Islam as the religion of the state. It was on his watch that Bangabandhu's killers were permitted by the authorities to form a political party, which then fielded one of the assassins as its presidential candidate at the 1988 elections. Politics was stood on its head when another assassin was made a member of parliament. And then, in a moment of supreme irony, the dictator went all the way to Tungipara to pray at the grave of the Father of the Nation.

Irony followed irony. Untruth reigned supreme, until the return of the Awami League to power, after a long gap of 21 years, in 1996 opened the path to a restoration of law, morality and decency in the land. Six of Bangabandhu's assassins have been hanged. Full justice will be done when their cohorts, fugitives around the world, are brought home --- to answer for their criminality.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a senior journalist and writer.

[email protected]