RANGPUR: While a peasant being oppressed by the British rulers for his aversion to planting a single sapling of indigo was a scene of bygone era, farmers of Rangpur are now cultivating the item amid great zeal and thus they are getting financially benefited.

After a long time, indigo cultivation has revived in Rangpur. But it is no more a curse for the peasants but a blessing for them.

A good number of peasants in Rajendrapur and Paglapir areas under Rangpur Sadar upazila have found the way to change their socio-economic condition through indigo cultivation.

Presently, indigo farming has been turned into a lucrative business for the peasants of the region.

According to the Department of Agriculture Extension (DAE), Rangpur, indigo is being cultivated on around 3,000 acres of land in Rangpur district. Some 2,000 peasants of the district are involved in farming of the crop.

Production cost of indigo is lower as it requires less or no irrigation and pesticides.

For these reasons, farmers are showing interest in its farming in recent years, sources said.

Sources said at the initial stage some farmers started farming indigo on fallow land near their homesteads in order to get organic fertiliser and fuels.

Gradually, cultivation of the crop turned out to be a profitable venture in the region.

The upper parts of the leaves are cut 2-5 times and sold for the production of indigo.

The lower part is used as fuel. Indigo plant is also a good source of organic fertiliser. Its farming increases the fertility of the land.

After the harvesting of potato and tobacco, land remains fallow.

Farmers cultivate indigo during the period before Aman farming.

Rabiul Islam, a farmer of the Paglapir area, said he has been farming indigo for the last six years.

Due to satisfactory profit, its cultivation is becoming popular in many areas of Rangpur, he added.

He said around 2.0 kg seeds are required to cultivate indigo on one acre land.

Some farmers said they are cultivating indigo and producing dye from it. They are getting adequate assistance from the local indigo leaf processing factory.

Locally produced indigo dye has already been exported to many countries including America, Canada, Japan and India.

Saiful Islam, an indigo farmer at Rajendrapur village in Rangpur Sadar upazila, said, earlier he had to struggle a lot to maintain his family.

He along with his family members suffered much due to abject poverty. "Earlier, we could not even eat two meals a day but now we can afford three meals a day", he said.

The cultivation of indigo has changed his fortune significantly. Now he is leading a happy life with his family members, he added.

"Indigo stick is a good fuel. We can make about Tk 5,000 to Tk 7,000 from selling the sticks," said Abul Kashem, a farmer of Rajendrapur.

DAE, Rangpur official sources said in the beginning, the farmers of Rangpur used to buy seeds from the market and cultivate them. Now they are producing seeds themselves and sometimes collect seeds from company.

Deputy Director of DAE, Rangpur, Dr Mohammad Sarwarul Haque said earlier, indigo was cultivated on a limited basis but in recent years commercial indigo farming is on the rise in the region. Some companies buy indigo leaves from local farmers and process them.

The word indigo points to South Asia. It derives from the Greek word 'indikon', which means, 'from India'. Ancient Greek imported their blue colourant from India.

Indigo, the last natural dye, was a highly priced commodity on the "Silk route".

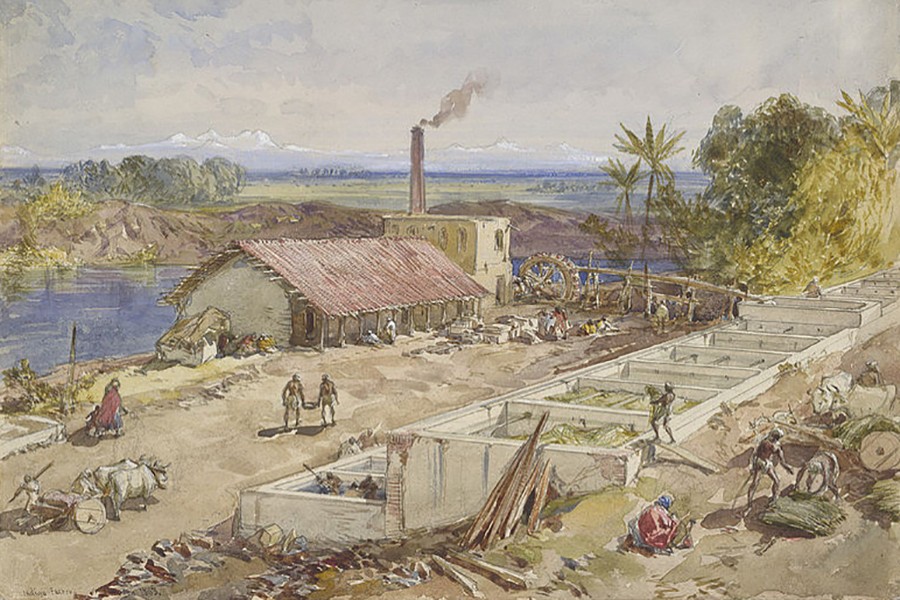

From 1600 onwards, the documents of the East India Company mention the production of indigo in India and its export. Gujarat and Sind were the major sources then. It made fortunes for farmers in mediaeval times.

The trade of Indigo from Asia was controlled by the Portugese in the middle of the sixteenth century. Indigo is a dyestuff that was a major item of international trade from the 16th to the late 19th century. The Spanish were their main competitors and were eager to get around the Portuguese supplies.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Central American indigo became a very successful product.

Central American indigo was being exported in huge quantities to Spain, Peru and Mexico.

Spain received its indigo and exported it to Britain and the Netherlands with extra duties.

Decline set in partly as a result of heavy taxation by the turn of the nineteenth century. The global indigo market was characterised by such imperial competition.

In their Caribbean and North American colonies, the French and the British set up successful indigo industries. The Dutch set up their indigo industries in Java.

In an increasingly competitive global indigo market, only those who could keep their cost of production low by employing cheap labour could make a profit.

The French saw an opportunity to rival indigo from British Bengal by planting Bengal indigo in Senegal, which was then a French colony.

Darrac being the former Chief of French Settlement in Dhaka for six years was in a good position to provide the report on indigo production in Bengal.

There was a little scope for the French to use French India as the location for a new indigo industry. Darrac's report covers that aspect as well when he discusses the similarities or dissimilarities of indigo production methods in India and Bengal.

According to sources since the soil of the Indian subcontinent was suitable for the cultivation of indigo, British indigo investors invested large sum in indigo cultivation.

Its cultivation started in Nadia, Jashore, Rangpur and some other districts. Indigo production and export was a lucrative business in Bengal province in the early 19th century.

But subsequently it proved non-profitable at farmers' level as a result farmers were turning to paddy and jute cultivation. Consequently, indigo cultivation gradually disappeared from Bengal.

Because of the Industrial Revolution in England, the demand for indigo was on the rise, and a major share of it happened to come from the subcontinent.

In Bengal, farmers were forced to grow indigo-instead of rice or other major crops-by the British rulers.

The farmers organised a resistance movement during 1859-60 which is called the 'Indigo Revolt' or 'Nil Vidroha' as the British indigo planters who invested huge capital forced them to cultivate it through tyranny and persecution.

It arose in Jashore and Nadia districts in the Indian state of West Bengal in 1859 and quickly spread to other districts. Extinct for more than a century, indigo is now being cultivated in Bangladesh, sources added.

From 1830 onward, the demand for indigo increased tremendously in the textile factories in Europe and Dhaka became the main distribution centre.

Cultivation of indigo started in 2000 under a project titled 'Nilkamol', involving Garo people at Jalchatra village in Madhupur of Tangail. Initially it brought 0.87 acres of land under cultivation.

As the experimental cultivation was successful, 12 acres of land were brought under the cultivation in 2001.

Next year, it started commercial cultivation at the village. Garo farmers cultivated indigo on 20 acres of land. But in 2003, the cultivation shrank to 12 acres as the farmers did not get seeds and other facilities. The cultivation increased this year.

Indigo is produced from leaves, which can be harvested three times a year.

Cultivation during March-April and harvesting during August- September is more profitable.