Only 20 per cent of the loans written off by banks in Bangladesh have been recovered in the last 12 years, says a new report.

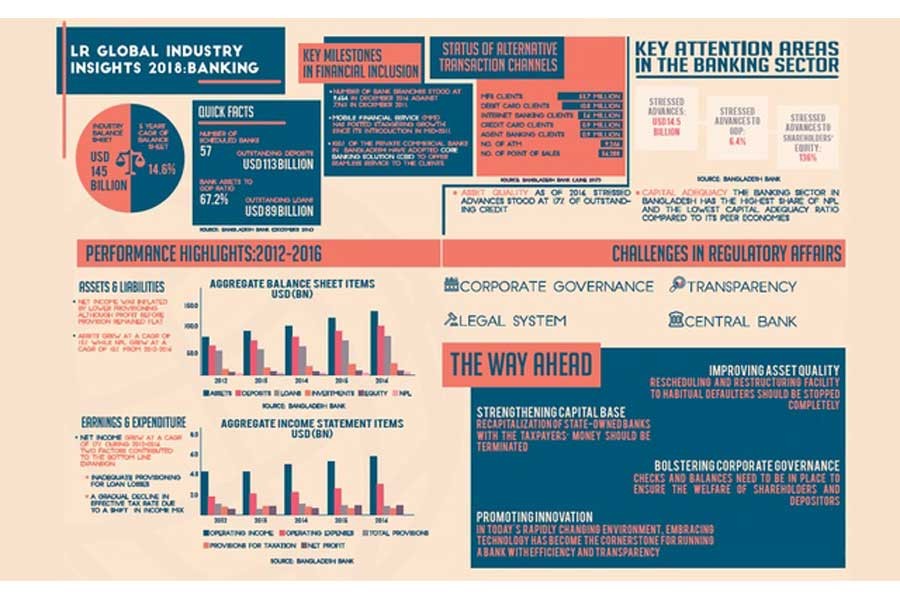

The study by LR Global Bangladesh says the country has the highest share of non-performing loans or NPL and lowest capital adequacy ratio or CAR, compared to its peer economies.

Bad debt grew faster than credit in the last five years, according to the asset management firm, an affiliate of New York-based LR Management Investments.

The aggregate credit grew at a compound annual growth rate of 13 per cent between 2012 and 2016, mostly in tandem with the nominal GDP growth.

By the end of 2016, non-performing, restructured and rescheduled loans stood at 17 per cent of total outstanding loans, according to the report.

The high loan defaults mean that the financial sector lacks the funds to absorb any sudden deterioration of asset quality, the report says.

It says non-performing loans grew at a faster pace in private banks than in the state-owned lenders in the last five years.

“Poor risk assessment of credit, subdued demand in the economy, rescheduling facilities to known defaulters, and mostly the culture of borrowers’ unwillingness to repay loans were the major reasons behind the deterioration of the asset quality in Bangladeshi banks,” reads the study, LR Global Insights 2018.

The state banks have failed to improve their capital position, asset quality and profit scenario despite recapitalisation by the government in the past nine years, says a bdnews24.com report.

The case of private banks is a bit different — it has been able to maintain sufficient capital in line with the regulatory requirements, but a major risk they face stems from their top borrowers.

Citing a stress test by the Bangladesh Bank, it said the top three borrowers in every bank would make up half of the bad debt.

The study said the central bank’s success in curbing non-performing loans was ‘limited’, but said its performance in monetary policy management, containing inflation and racking up a healthy foreign exchange reserves was commendable.

Pointing out that most of the banks are controlled by families or related business, the report says the planned change in the banking law will likely lead to ‘further consolidation of power in the hands of too few.’

In May, the government moved to amend Banking Companies Act allowing four members of one family to be directors, up from the previous two. Directors will be able to serve three consecutive three-year terms, compared to the two straight terms now.

The study, however, described the magnitude of the problem in the banking sector as ‘manageable’ and said: “The regulators cannot afford further denial and must take preemptive actions to reform the system when there is still time.”

The banking system, however, has made considerable progress in financial inclusion, said the report citing 9,654 bank branches by the end of 2016 from 7,961 in 2011.

It said agent banking that kicked off in 2013 has seen tremendous growth. “Fresh deposits worth $115 million and loan disbursement worth $10 million were made in rural and previously unbanked areas.”

A staggering growth in mobile banking, since its introduction in 2011, has facilitated faster transactions to every corner of the country.

Tech-savvy urban consumers and the rise of e-commerce have also led to growth in plastic money.