Scientists in Cambridge have built a virtual reality (VR) 3D model of cancer, providing a new way to look at the disease.

The tumour sample, taken from a patient, can be studied in detail and from all angles, with each individual cell mapped.

Researchers say it will increase our understanding of cancer and help in the search for new treatments.

The project is part of an international research scheme.

How it was done

- Researchers start with a 1mm cubed piece of breast cancer tissue biopsy, containing around 100,000 cells

- Wafer thin slices are cut, scanned and then stained with markers to show their molecular make-up and DNA characteristics

- The tumour is rebuilt using virtual reality

- The 3D tumour can be analysed within a virtual reality laboratory

The VR system allows multiple users from anywhere in the world to examine the tumour.

Prof Greg Hannon, director of Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute (CRUK), told reporters: "No-one has examined the geography of a tumour in this level of detail before; it is a new way of looking at cancer."

The 'virtual tumour' project is part of CRUK's Grand Challenge Awards.

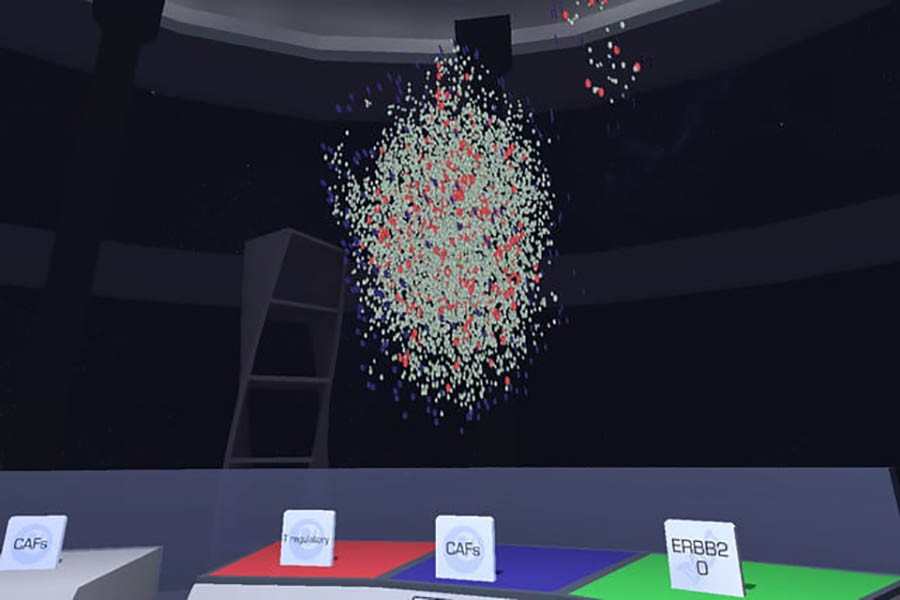

Within a 'virtual' laboratory, Prof Hannon and I became avatars, whilst the cancer was represented by a multi-coloured mass of bubbles.

Although the human tissue sample was about the size of a pinhead, within the virtual laboratory it could be magnified to appear several metres across.

To explore the tumour in more detail, the VR system allowed us to 'fly through' the cells.

The virtual tumour we were looking at through our headsets was taken from the lining of the breast milk ducts.

As Prof Hannon rotated the model, he pointed to a group of cells that were flying off from the main group: "Here you can see some tumour cells which have escaped from the duct.

"This may be the point at which the cancer spread to surrounding tissue - and became really dangerous - examining the tumour in 3D allows us to capture this moment."

Prof Karen Vousden, CRUK's chief scientist, runs a lab at the Francis Crick Institute in London which examines how specific genes help protect us from cancer, and what happens when they go wrong, reports BBC.

She elaborated: "Understanding how cancer cells interact with each other and with healthy tissue is critical if we are going to develop new therapies - looking at tumours using this new system is so much more dynamic than the static 2D versions we are used to."