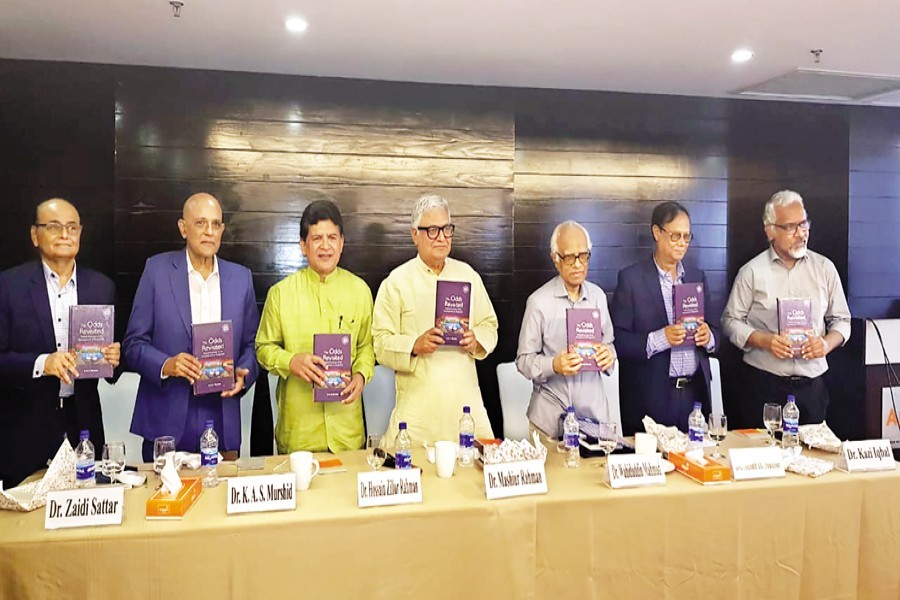

Bangladesh may not have achieved an economic miracle but its journey on the road to development against all odds so far has been highly appreciable. This is exactly why the development paradigm of this once basket case-famed country has ever remained an enigma to notable financial experts around the world. Eminent economist of the country Dr. Wahiduddin Mahmud, while speaking as the guest of honour at a book launching ceremony in the city has, however, outlined the efforts that went into the making of what Bangladesh today is. According to him, the country's socio-economic transition came on the strength of a combination of efforts. Whatever was the type of regime -- no matter if there was no accountability, everyone concentrated on reduction of poverty in order to legitimise the respective rules. The role of development partners and non-government organisations helped but above everything else it was the hardworking people of the country who lent their hands into the effort as part of their survival instinct.

Dwelling on this theme, Dr. Mahmud then raised the more pertinent question relevant to the next course of journey. Against the backdrop of the post-pandemic crises -- both natural and manmade with a famine looming large globally -- and on the eve of the country's graduation in that critical situation, how much is the country prepared to take that journey? Professor Mahmud and other leading economists who participated in the discussion there, were unanimous that the country's economic progress was made possible so far on the strength of cheap labour -- most strikingly in the RMG sector, but this will prove useless to face the challenges of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) the world is poised to embrace. Required infrastructure, good governance, financial and banking reforms, accountability are a sine qua non but it is the improved and diversified skills of the human resources that will clinch the day.

Bangladesh is lagging not only the advanced countries but even some of the South and South-east Asian nations in this regard. A highly significant factor is the low quality of education and a lack of investment in research at the tertiary level of education. Evidently, a culture of research in the country's academia has not grown mostly because neither the government nor the corporate and industrial sectors have felt the necessity to collaborate with the universities in augmenting research and innovation. Without such collaboration and investment, a country's scientific and technological talent pool cannot be developed suited to the special need of a country.

This is further corroborated by the global rankings of the country's universities. For career building of the average students, the best option is either vocational or technical education and training. At least, this can help them avoid the low-end employment and a pittance of wages abroad. But to meet the challenges of the 4IR, the country will have to upgrade its education in terms of science, technology and innovation. A culture of creativity has to be encouraged by way of making space for the highly talented people. An appropriately developed mindset of governance has also to be there in order to encourage and expedite the process.