The pyramid shape of modern bureaucracy is an accepted, even an essential norm. Very recently an analytical report in the front page of our newspaper brought to the fore the bulge around the apex of the administrative structure. Only below the secretary proper level, whose number has somehow been kept within rules, almost the whole body consists of additional secretaries, joint secretaries and deputy secretaries. Although there is a dearth of officers at the assistant secretary-level, the desk post that starts the machinery of the government rolling, all other officers have become holders of posts between senior assistant secretaries to additional secretaries. The report that 498 additional secretaries were working against 121 sanctioned posts and 869 joint secretaries working for 411 available stations points to an inexplicable mismatch. What those extra people at higher positions with accompanying pay packets and facilities are doing at the expense of the tax-payers' money is an obvious question to ask. The case of the deputy secretary level is more pitiable, with over seventeen hundred officers sitting for a thousand posts and many of them doing the work of the desk officer, one or two tiers below. The government has not expanded its apparatus by any formal pronouncement; neither has new workload ushered in overnight. Only after the promotions are effected does anyone come to know about the postings. That positions were not there is subsequently proven by the large-scale notifications for appointment as officers-on-special duty.

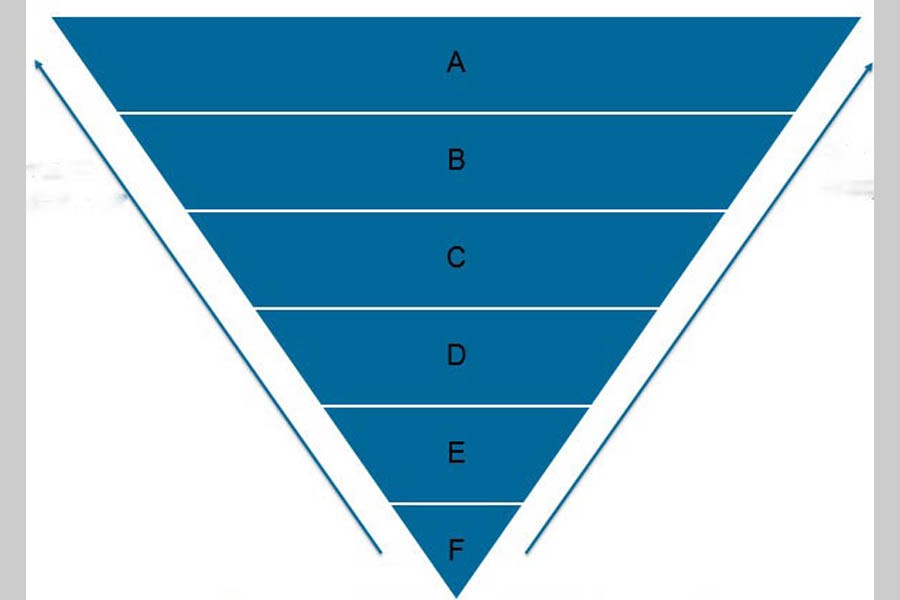

Besides, dearth of sitting arrangements has led additional secretaries and joint secretaries to occupying the space of a desk officer in some cases. Service delivery has been hampered with a four-tier structure giving in to at least a five-tier one. And indeed, as noted by Dr Akbar Ali Khan, a prominent civil servant of yester years, all these have given rise to an 'inverse pyramid' in the secretariat in place of the pyramid as we have known it. Other experts have also talked about procedural delay and loss of motivation. The way Civil Service promotions have been being dealt with at the secretariat in recent times may be dubbed opaque. The tricky arithmetic behind it will not be understood by even the serious mathematician, let alone a commoner. Then, if one considers the costs of it, one gets dumfounded. Whatever may be the numerical or administrative justification behind the promotion orders, one thing is clearly focused: care has been taken to make people happy with higher positions without adequate regard for rules, results and costs.

What we wish to underline is that while field posts have remained more-or-less the same, all pressure has been applied to the Bangladesh Secretariat, the nerve-centre of the administration, and that this must be rolled back. This is the right time to be seized with the issues and remove the cumulative anomalies in the system. While public service examinations have been held in a proper manner in recent decades, its consequential products have floated in uncertainties in the post-recruitment phases. There must be a clear path ahead for everybody. Those falling on the wayside must be convinced that it was largely because of their own fault and lack of quality that they could not get to the desired levels. The need of the hour dictates that 'inverse pyramid' be given the right shape to provide good governance, speed up service delivery, and above all, maintain chain of command and uphold high morale of the services.