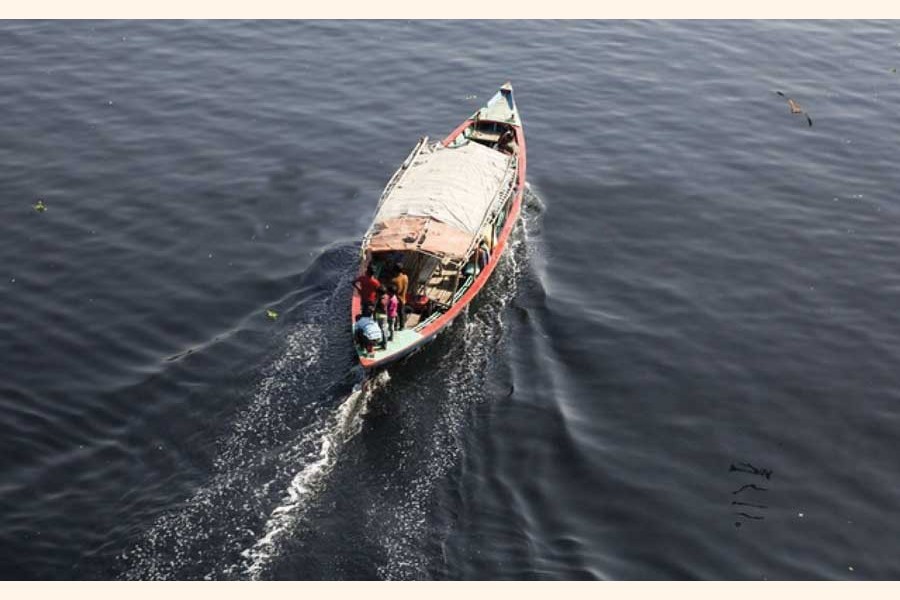

The Mediterranean Sea route used by illegal migrants from various nations to reach Italy and Greece has by now become infamous for breakdown or capsize of boats and consequent sufferings including starvation in the open sea and, in the worst cases, mass drowning. All this, however, has failed to deter desperate Bangladeshi youths from embarking on such clandestine and perilous journeys. On June 24 last, Tunisian coastguards rescued 267 such migrants, 264 of them from Bangladesh, who were bound for Italy. A couple of days ago, five Bangladeshi youths were rescued from the sea off the Caribbean coast. Reportedly, a group of 10 Bangladeshis started from Colombia on a boat that capsized and five of them are missing. In the last three months 485 Bangladeshis bound for Europe were rescued in Tunisia and during an earlier rescue mission on May 17, of the 81 on board a boat, 68 could be rescued and the rest 13 are unaccounted for.

It is a long and tragic saga of migration by Bangladesh youths. They spent months in Thai forests on their way to Malaysia, many died of torture and starvation, some perished in waters of the Bay of Bengal, the Mediterranean and the Arabian seas. Even before reaching sea coasts in foreign lands, they have to make long and arduous odysseys up to Libya or Colombia. How do they do it? The young people who embark on such uncertain and perilous journeys receive low level of education but are encouraged by friends and people they know, who have somehow landed on a foreign soil and are living there, legally or illegally. But unless there is a strong chain of international human traffickers, they are unlikely to cross transnational borders with the travelling repertoire they have as international tourists. What is baffling is that the restrictions like lockdowns could not stop their movement through several national boundaries. Can it be that deserted roads and localities facilitated the illegal activities of the traffickers?

Even then it is unbelievable that traffickers can have a field day unless the law enforcement agencies become a party to the vice in exchange for booties. The coastguards cannot help rescuing lives in danger but at times the tragedy happens before they can intervene and at other times the illegal human cargo successfully anchor at the desired coasts. From this one thing is clear that even in the host country, there is a demand for such illegal and cheap labour. Malaysia launched drives against illegal foreign workers and deported some but also allowed work permits if they reported within a stipulated time. Many other countries have done so.

All this points to the fact that international migration warrants streamlining and the chains of human traffickers dismantled once and for all. Migrants should be given the opportunity to move to their desired destinations if their skills or labour are in demand there. This can happen through official channels unlike under the coercive supervision by manpower agents. First, such agents demand a fat amount of fee and then many of them are unreliable. When Bangladesh is about to become a middle-income country, the tragic loss of young lives in seas and foreign lands as well as languishing of youths in camps of International Organisation of Migration (IOM) is disgraceful.